Background

Among the unfortunately overwhelming compendium of controversial topics within the field of nutritional science, very few attract as much attention as soy and its effect on human health. Consulting various forms of online media, literature, and even many health professionals, one may quickly find that for every positive effect surmised to arise from greater consumption of soy-based products, there is a competing claim about its potential harms, and then some. Despite the seemingly constant arguments between both health professionals and laymen concerning the true benefits and harms attributed to its consumption; the current high-quality human-based evidence undoubtedly leans strongly in one direction. Accordingly, the following discussion will serve to provide a relatively easy-to-digest summary of the findings from the literature on soy, and address many of the common questions and concerns surrounding the topic along the way, ranging from minor misconceptions to blatant pseudoscience.

Is Soy truly Harmful?

Probably one of (if not the most) frequent concerns surrounding soy consumption is that it has been assumed to impact plasma hormone concentrations. It is surmised that these supposed changes lead to adverse or undesirable outcomes, a major one being the all too common trope that soy exerts “feminizing” effects and gives men breast tissue. Many of these ideas originally manifested from observations that soy contains naturally occurring phytoestrogens (or “plant estrogens”) that are absorbed in the gut (predominately the isoflavones genistein and daidzein). The subsequent occurrence of adverse effects in two human case studies and some animal studies have compounded the concerns. However, the test animals in these studies are typically given massive doses of isolated components found in soy, so aside from the fact that they have incredibly poor translation rates to humans (as detailed in the previous article on plant-based protein), the circumstances aren’t even representative of normal human exposure. As for the case studies, not only were the subjects were consuming highly restrictive diets with amounts of soy products beyond what anyone would consider normal; a 60-year-old male having three quarts of soy milk daily, and a 19-year-old with type 1 diabetes consuming a diet containing “soy milk, soy cookies (soy crisps), tofu, soy sauce, soy nuts, and soybeans (edamame)”, but it was never even strongly confirmed that the soy products caused the issues observed (gynecomastia and erectile dysfunction), they simply dissipated upon adoption of a more balanced diet¹’². Second, it is also unknown if either of them had a specific sensitivity to soy that could have left them particularly susceptible to any of these effects, which is certainly an important consideration. Finally, case studies are some of the lowest forms of evidence available, and should never be used for general prescriptive advice, be it pertinent to nutrition, medicine, or any other health-related field. This should become clear when considering that the specific occurrences recorded in these cases were so rare that they warranted documentation, emphasizing exactly why they lack relevance to advice addressing the general population.

Confusion Surrounding Phytoestrogens

Moving onward to the briefly aforementioned phytoestrogens; these are a collection of compounds that are similar in structure to 17-beta-estradiol, the active form of the steroid hormone estrogen found in humans and other mammals. However, this is an incredibly simplistic overview, and drawing conclusions about phytoestrogen’s effects simply due to their likeness to estradiol would involve ignoring an enormous amount of detail that actually identifies how they are quite different from the latter. While it is true that phytoestrogens can bind to estrogen receptors, their affinity is 1/100 to 1/10000 of typical 17-beta-estradiol, and they preferentially bind estrogen receptor beta (ERb). Additionally, genistein possesses a 20 to 30-times higher binding affinity for this receptor, whereas daidzen has an even lower affinity for both alpha (ERa) and beta (ERb) receptors. A secondary metabolite of daidzen only produced in an estimated 30–50% of people; equol, has a slightly higher (10 fold) binding affinity for ERb. The distinction between these receptors is important since ERb can act as a modulator of ERa’s activity, reversing the downstream effects resulting from the binding of estrogen compounds to ERa, many of which are associated with the adverse effects resulting from high estrogen concentrations. Henceforth, phytoestrogens can act either as receptor agonists or antagonists and have in turn been suggested to be “selective estrogen receptor modulators”³. As fascinating as the complexity of this biochemistry is, the real questions that need to be asked are, “Do these phytoestrogens meaningfully influence serum hormone concentrations?”, and more importantly; “Do phytoestrogens or any of their metabolites exert changes via receptor binding (or other mechanisms) that cause detrimental, beneficial, or no effects in humans?”

Soy and Hormones

Women

Luckily, there is a surplus of research capable of answering these questions across a wide variety of demographics. Although claims about supposed harms vary considerably from group to group, the effect of soy and/or its isoflavones on the hormone levels of women will be discussed first.

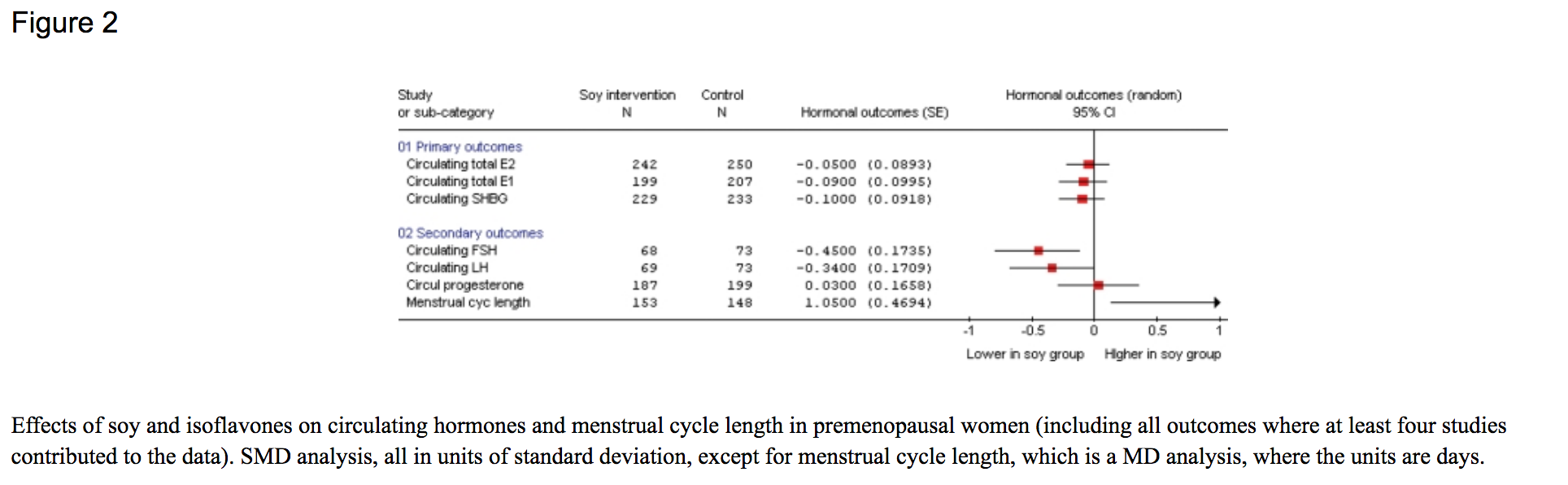

In a 2009 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on 4+ week interventions including soy or their isoflavones, it was determined that in pre-menopausal women there was no significant effect of soy on estradiol, estrone, or sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) concentrations, but there was a significant reduction of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). The duration of menstrual cycles increased slightly, by a single day. Conversely, none of these measurements changed significantly in post-menopausal women, with the only observation being a slight, non-significant increase in total estradiol. Furthermore, the effects on FSH and LH were attenuated in a sensitivity analysis that included only higher quality trials at low risk of bias. Finally, as discussed by the authors, an increase in menstrual cycle length has been implicated in a decreased risk of breast cancer, suggesting this effect is most likely a desirable change.

Considering these findings authors concluded with very little certainty that soy/isoflavones may decrease LH and FSH in pre-menopausal women, and potentially increase total estradiol in postmenopausal women. However, they emphasized that the clinical implications of these minor changes are unclear⁴. Such findings highlight why focusing on measurable health outcomes, as also mentioned repeatedly in the previous article on plant-based protein, is so important.

Men

Shifting the focus to men, a 2009 meta-analysis of 15 RCTs on soy foods/isoflavones in adults had similar findings; there were no significant effects observed on measures of testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, free testosterone, or free androgen index⁵. Furthermore; a recent update to this meta-analysis published just a month ago, including 41 trials, confirmed that consumption of soy isoflavones or protein (in isolation or as whole soy foods) had no significant impact on total testosterone, free testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, estradiol, and estrone in men aged 18 to 81 years old; regardless of the statistical model used to assess their effect (depicted below).

Reviewing these findings, the authors remarked:

In conclusion, extensive clinical data published over the past two decades shows that in men neither soy nor isoflavone intake, even when exposure occurs for an extended period of time and exceeds typical Japanese intake, affects levels of total testosterone, free testosterone, estradiol or estrone.⁶

In summary, the highest quality evidence currently available suggests that consumption of soy, soy isoflavones, or soy protein does not significantly affect the concentrations of any major hormones in men, and very weakly indicates that it could cause a minor decrease in LH/FSH in pre-menopausal women, and a non-significant increase of total estradiol in postmenopausal women. On that note, it’s also worth mentioning that many trials employed isolated doses of these compounds that were well above those typically achieved via dietary intake, even those observed in countries with the highest per capita consumption of soy. All that said, the real question is whether the absence of an effect, or the small effects seen in certain subgroups with increased soy isoflavone intake, have a beneficial, harmful, or neutral effect on long-term health outcomes.

Influence of Soy on Health Outcomes

While there seem to be an endless number of health-related outcomes that soy (or any other food for that matter) may influence, the following discussion will focus on addressing those most common conditions claimed to be impacted by soy consumption, along with a few other major chronic diseases prevalent in modern day societies.

Among the most frequent concerns surrounding the consumption of soy is that it may negatively influence the risk of, or outcomes associated with, a collection of hormone-related chronic conditions in women. Two of these include breast and endocrine-related (namely endometrial and ovarian) cancers. Soy is hypothesized to affect these due to the fact it contains the aforementioned phytoestrogens, and that estrogen (largely via estrogen receptor activation) is a major modulator of the risk of these cancers⁷’⁸. Additionally, it is also regularly cautioned for those with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) to avoid soy; however, the reasons brought forth to justify this caution are sporadic in nature and vary substantially between sources. Lastly, it is sometimes claimed that soy can even worsen premenstrual syndrome/menopausal symptoms, and increase the risk of endometriosis. While these assertions are frequently made by many individuals (including a variety of health professionals) with a strong degree of confidence, it should soon become apparent that the data indicates the exact opposite.

Breast Cancer Risk

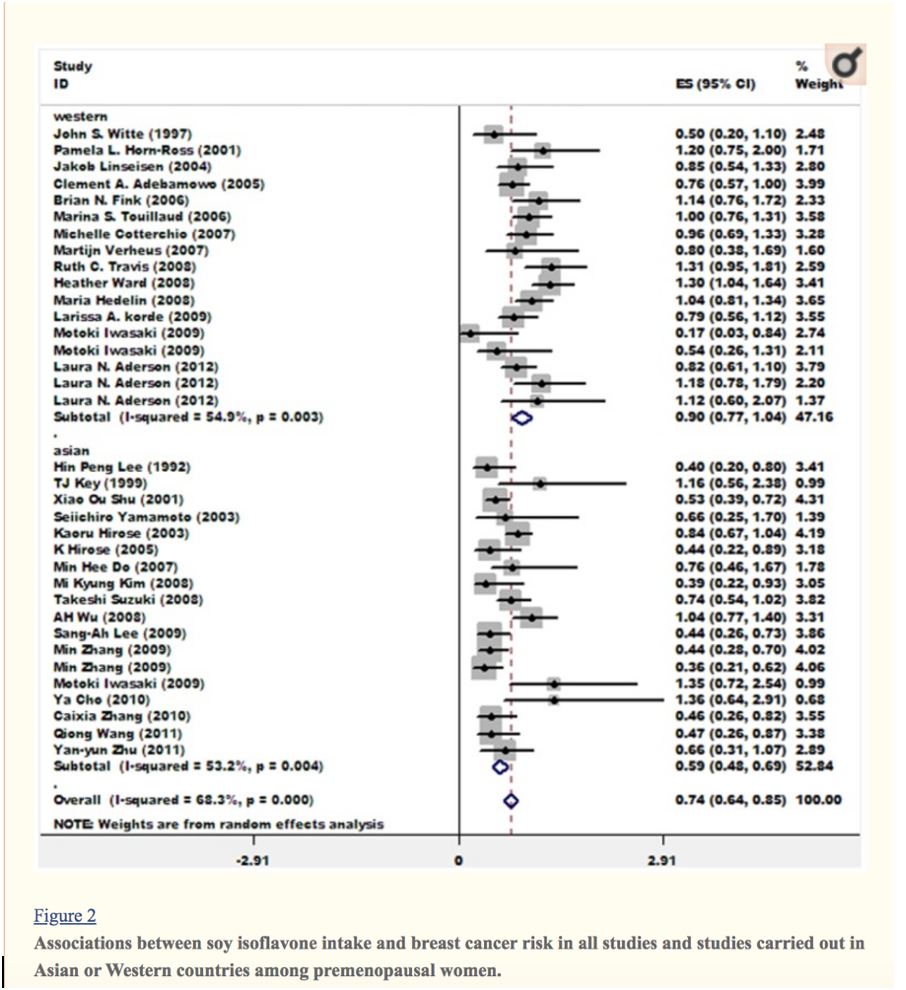

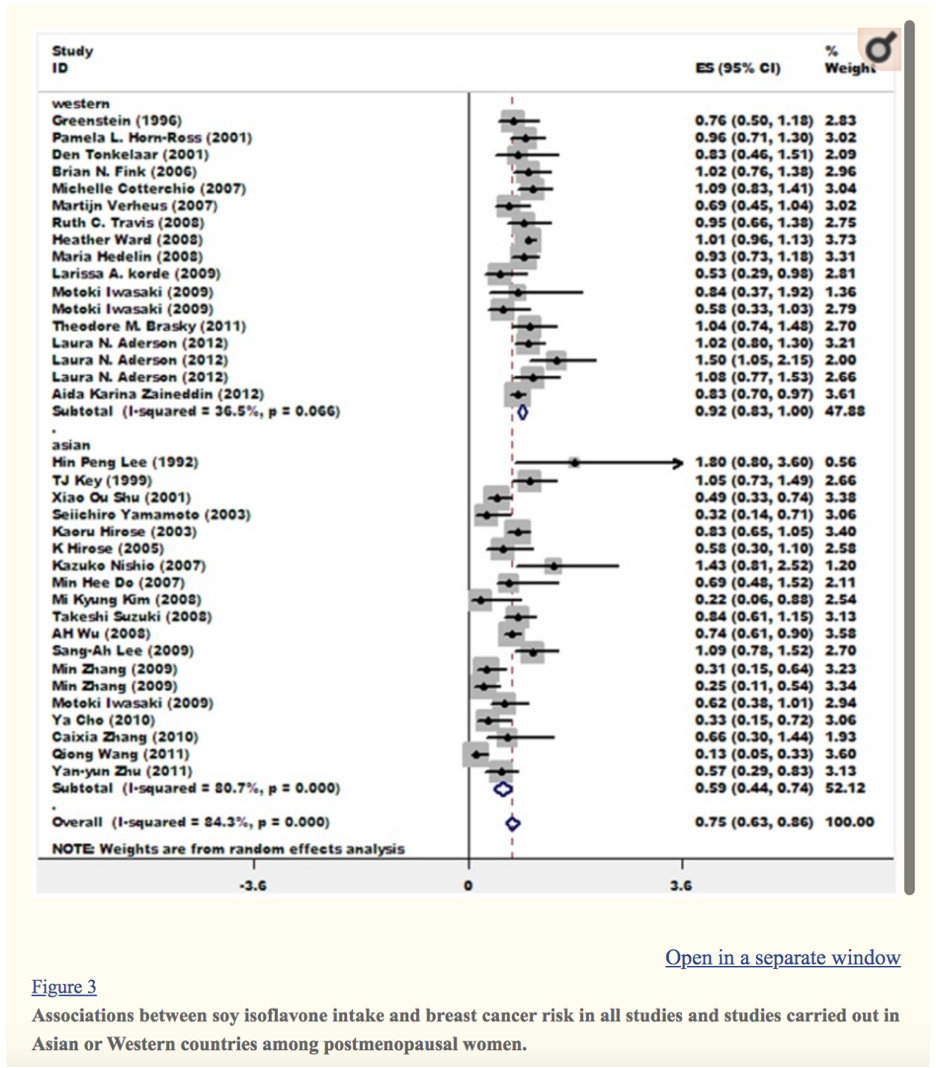

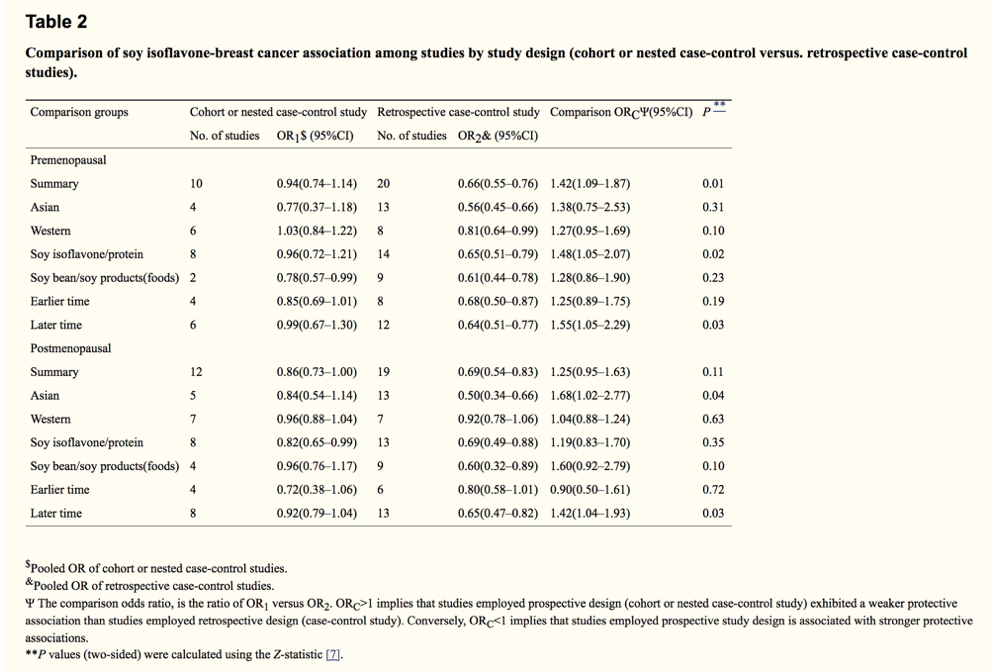

The totality of the current research observing the relationship between soy consumption and the risk of breast cancer suggests it may actually exert a positive effect. In a 2014 meta-analysis including 35 studies from Asian and Western countries, it was shown that soy isoflavone intake was inversely related to (decreased) the risk of breast cancer in both pre and postmenopausal women. However, the authors noted that this association was limited to Asian countries, and in some instances was modified by study design (i.e., results observed in cohort or nested case-control studies differed significantly from those of retrospective/case controls)⁹.

There are quite a few reasons as to why these differences are to be expected, but before expanding upon these it should be noted that even if just the information provided by this meta-analysis were taken at face value, there is very clearly no basis for believing soy consumption would have anything but a neutral or beneficial effect.

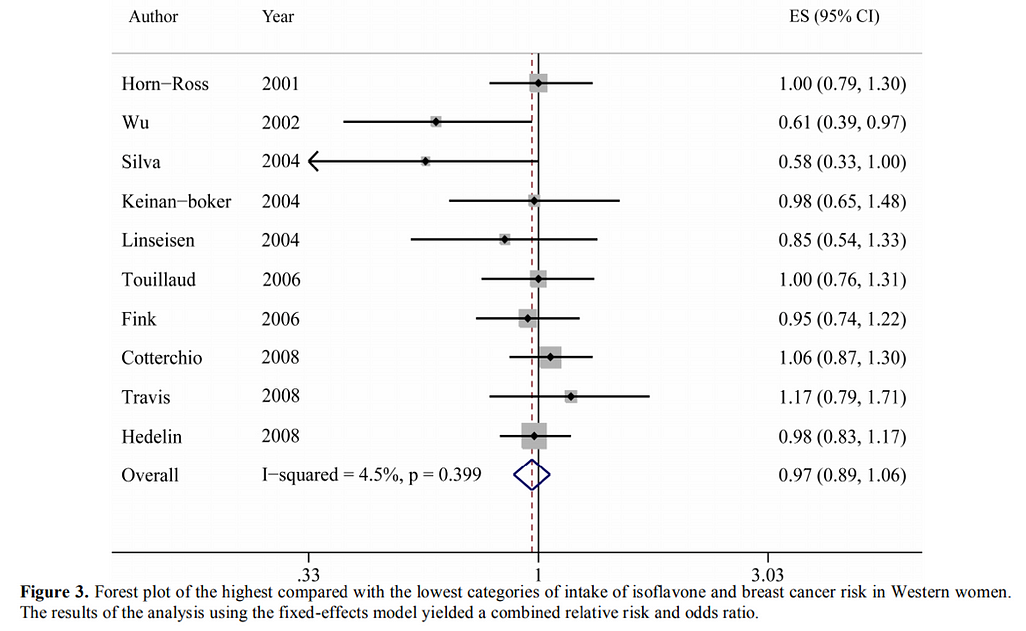

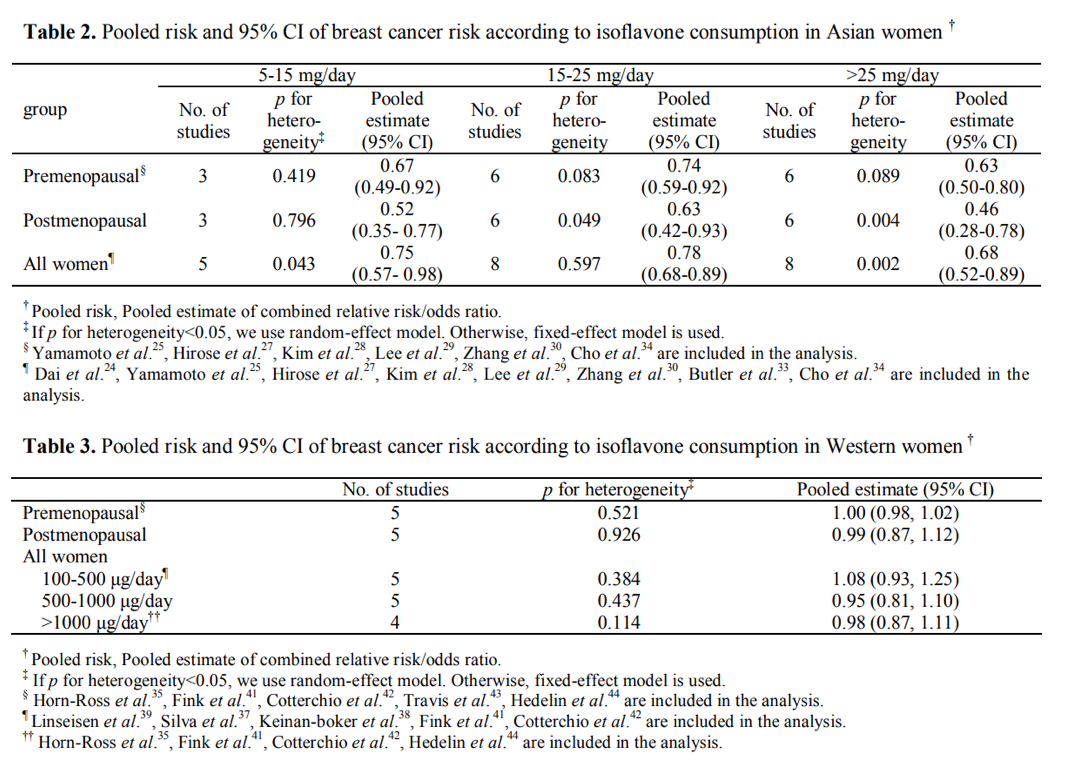

That said, probably the most notable caveat here was the difference in the results from Asian countries and Western countries regarding the influence of soy consumption on breast cancer incidence. There are a vast array of reasons one could posit as to why this difference exists, but there is one surprisingly simple explanation that is beautifully outlined by a previous meta-analysis on soy isoflavone intake and the risk of breast cancer. This meta-analysis had similar findings, showing a significant reduction in the risk of breast cancer with higher soy consumption among Asian pre and postmenopausal women, but none in those from Western countries.

Just considering this data, one may question how this publication could possibly elucidate the reason for the differences observed. The answer to this question lies in a minor difference in methodology. The authors of this paper decided to conduct a dose-response analysis to determine if there was a potential dose-dependent effect of soy consumption on breast cancer risk. When they observed Asian countries, even the lowest consumption range of the three they considered conferred a protective effect, whereas not a single one of the ranges in Western countries showed the same. However, looking over the tables, it becomes evident that the difference in the average and range of soy/soy isoflavone intakes in Asian and Western countries was astounding. So much so, that even the highest intake range considered for Western countries fell below the bottom end of the lowest range of intakes within Asian countries. As to be expected, this appears to be close to where a beneficial effect of soy isoflavone intake begins to be observed given that the upper confidence interval of the lowest intake range of Asian women is fairly close to suggesting a potential null effect¹⁰.

Henceforth, it is likely that such minuscule intakes like those seen in Western countries would not be sufficient for assessing the influence of soy on breast cancer risk, and it would be quite inappropriate to include these in a pooled analysis of the effects recorded in all the studies without stratification by dose. This may seem like a small consideration, but it is incredibly important and makes a world of difference when it comes to ascertaining the effect of a certain variable (in this case, soy consumption) on an outcome of interest. Unfortunately, this is far from an issue unique to this specific area of research and applies to numerous other meta-analyses concerning dietary habits and their impact/s on disease risk.

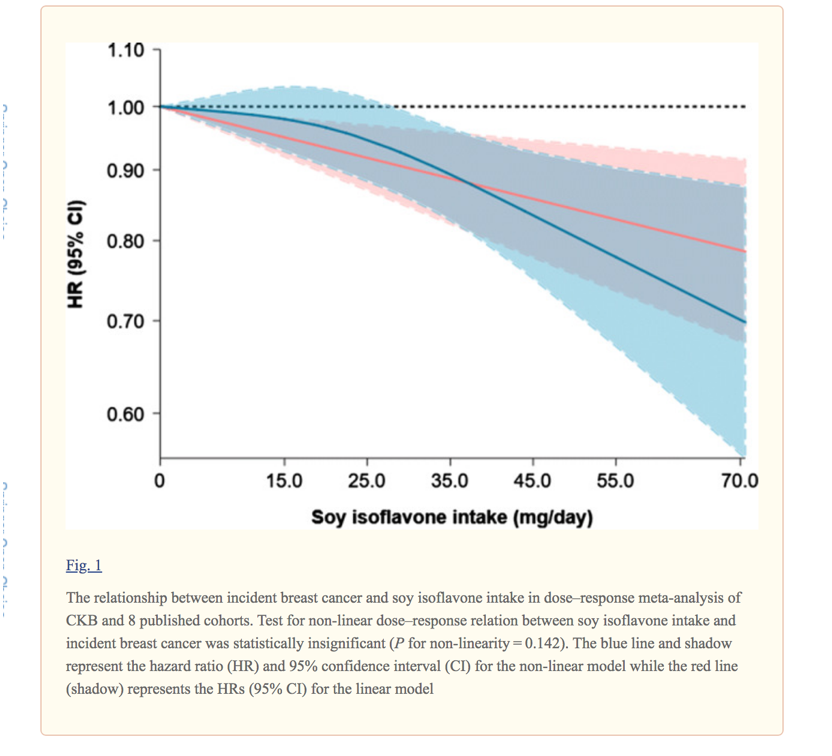

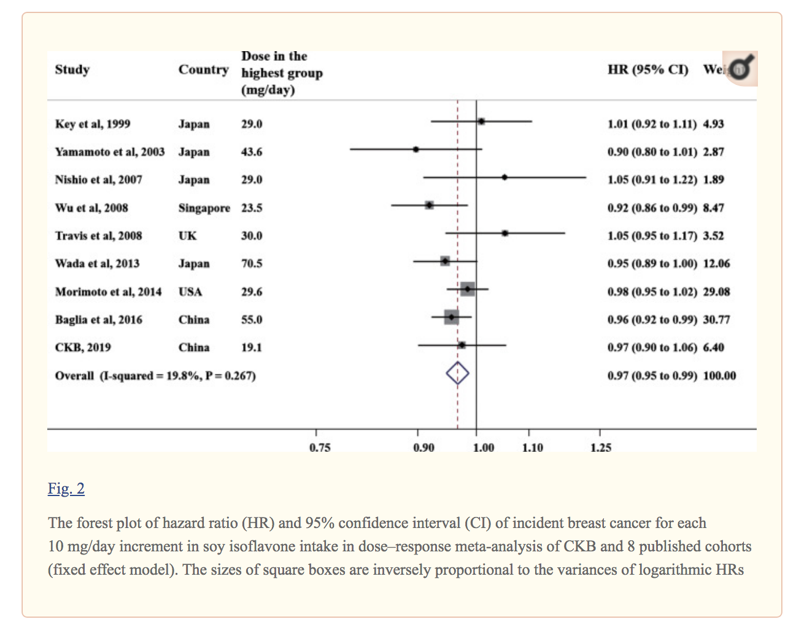

Even further solidifying this point are the results from another recent dose-response meta-analysis of soy intake and breast cancer risk carried out by Wei et al. Their analysis of 9 prospective cohorts (including their own China Kadoorie Biobank cohort, and only 3 of which were found in the previous meta) demonstrated that even just a small daily 10 mg increase in soy isoflavone intake coincided with a significant reduction in the risk of breast cancer.

In their concluding paragraphs they make the following statement:

In the present dose–response meta-analysis, the breast cancer risk reduced by each 10 mg/day of soy isoflavone intake as weakly as 3%, which may explain why most individual studies (including CKB) with low to moderate level of soy isoflavone intake failed to detect a statistically significant soy-breast cancer association.”¹¹

This once again demonstrates how important it is to take dosage into account while carrying out this type of research.

Breast Cancer Post-Diagnosis Mortality and Recurrence

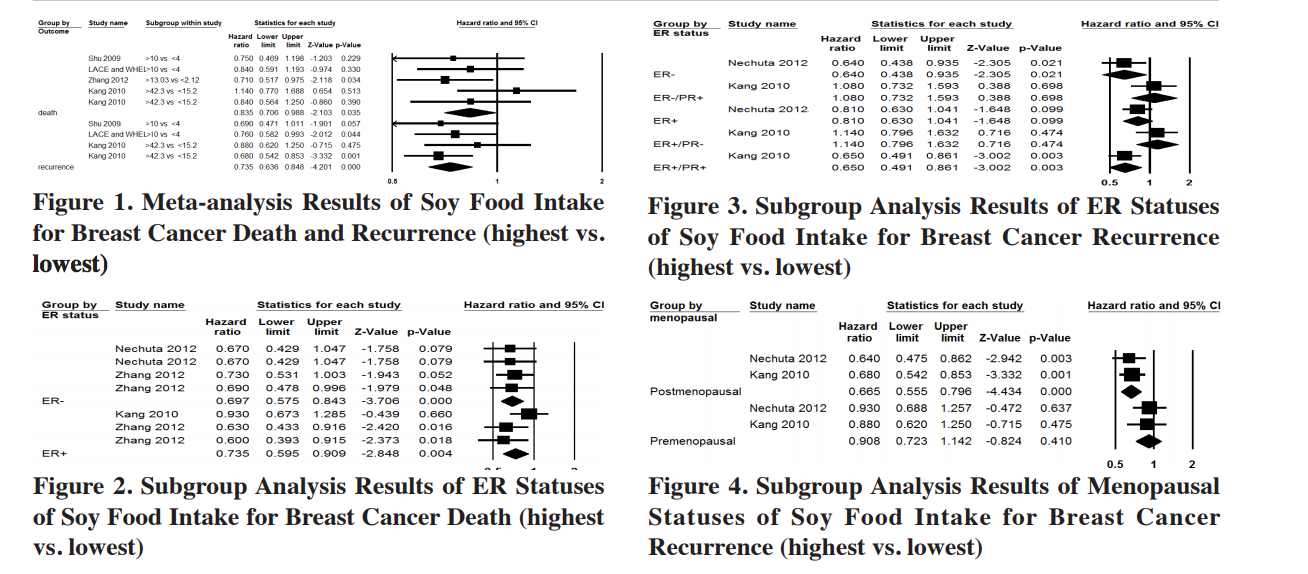

In addition to potentially reducing the risk of breast cancer incidence, there is some evidence to suggest soy isoflavone intake may even improve post-diagnosis mortality in individuals previously diagnosed with breast cancer. A 2013 meta-analyses pooling 5 cohorts on post-diagnosis soy intake and breast cancer mortality indicated that higher intake may reduce cancer mortality in estrogen-positive or negative pre- and post-menopausal women, and recurrence in ER-negative, ER+/PR+, and post-menopausal women. Unfortunately, they were unable to conduct a dose-response analysis, but most of the cohorts appeared to have appreciably “high” intake quantiles and a notable gap between high and low¹².

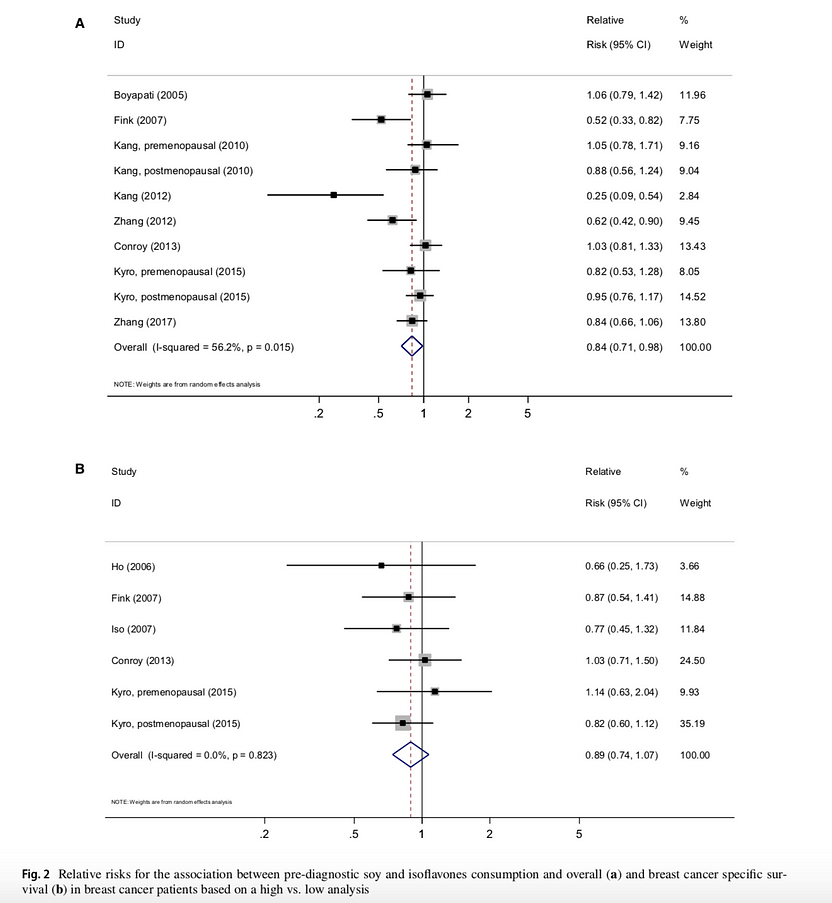

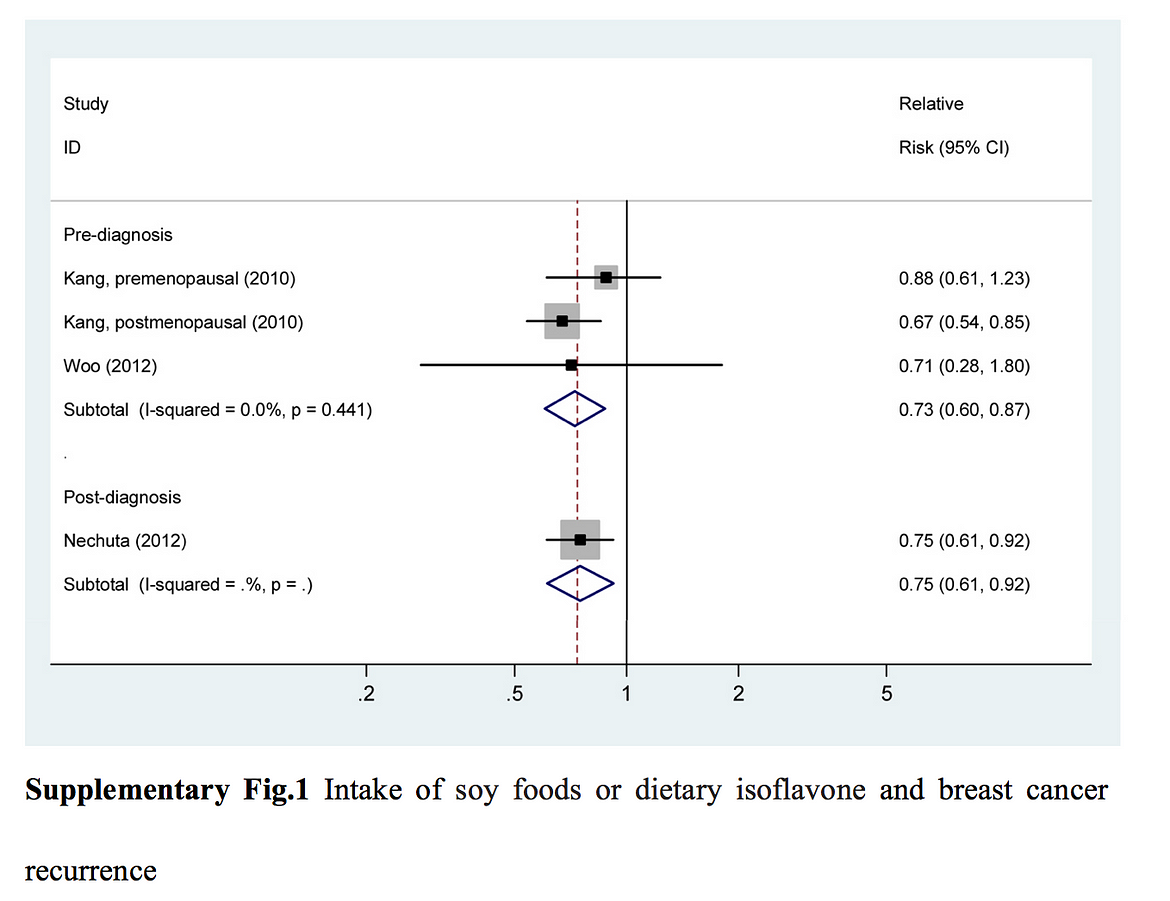

Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis from 2019 including 12 cohorts suggested that while pre-diagnosis intake may increase overall survival (especially in post-menopausal women), it did not seem to impact breast cancer-specific survival. Although higher post-diagnosis soy intake did not significantly impact overall or breast cancer-specific survival, it did (alongside pre-diagnosis) appear to decrease the risk of recurrence¹³. Unfortunately, despite conducting a high vs. low analysis (with incredibly limited data; only two cohorts for overall survival and one for breast cancer-specific survival), this meta suffers the same issue that those on breast cancer incidence do; many cohorts had very low intakes with small changes from the bottom to the top quantiles.

So, while not nearly as consistent as the evidence on the decreased risk of breast cancer observed with higher soy intake (arguably of more importance), the current data hints that its impact on overall and breast cancer mortality is positive, especially in post-menopausal women. There should certainly be a focus on conducting additional large, prospective cohorts to better identify the nature of this effect. With that being said, akin to the effect of soy on breast cancer risk, even if it was not necessarily positive, findings still give no rationale for concluding that it is somehow harmful, as the meta-analyses reviewed here do not support this assumption with a modicum of certainty.

Endocrine-Related Gynecological Cancers

Similar to breast cancer, due to the role of hormones in endocrine-related gynecological cancers, many women are cautioned against consuming soy under the impression it will increase their risk of contracting these diseases. Though the studies on these cancers contain methodological pitfalls akin to those seen in breast cancer survival research, they are also similar in the sense that results follow the same trend, overwhelmingly pointing towards a positive or neutral effect.

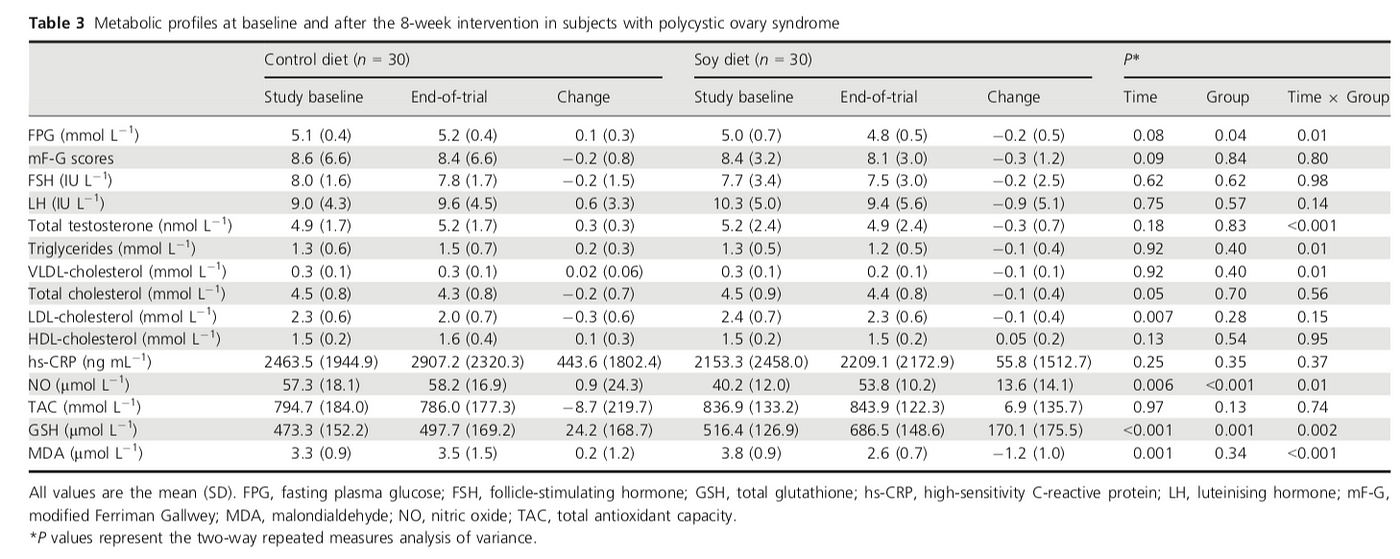

An earlier meta-analysis from 2009 on soy intake and endocrine-related gynecological cancer including 7 cohorts (2 prospective and 5 case-control) suggested that higher soy intake significantly reduced the risk of endometrial and ovarian cancer, along with overall gynecological cancer risk, in both study designs¹⁴. While the amount of data contained in this analysis was fairly limited, it spurred further research on the topic.

In a 2014 meta-analysis of 10 epidemiological studies (6 case-control and 4 prospective cohorts), Qu et al. found that greater isoflavone intake may decrease the risk of ovarian cancer. They also decided to carry out a meta-regression to identify what other factors may modulate this relationship. The most interesting finding here was that when they stratified by region, those with the highest, a large range of, and sustained intakes (especially China, and surprisingly an appreciable amount of US cohorts) – specifically of soy phytoestrogens, experienced the greatest risk reduction. This finding further demonstrates the importance of considering dose-response as touched upon previously, in addition to the duration and range of intakes¹⁵.

Another meta-analysis from 2015 that instead honed in on endometrial cancer risk provided some additional data, including 10 studies (8 case-control and 2 prospective cohorts). The authors’ overall findings implied that higher soy consumption could significantly reduce endometrial cancer risk, especially in post-menopausal women. Conversely, there was no significant effect observed when the two prospective cohorts were pooled, or in premenopausal women. Sadly, due to a lack of a dose-response analysis, and very small sample size for both, the power of the analyses to identify an effect was seriously hindered. Accordingly, the authors emphasized that their results suggest that soy may be protective, but that further prospective cohorts are warranted¹⁶.

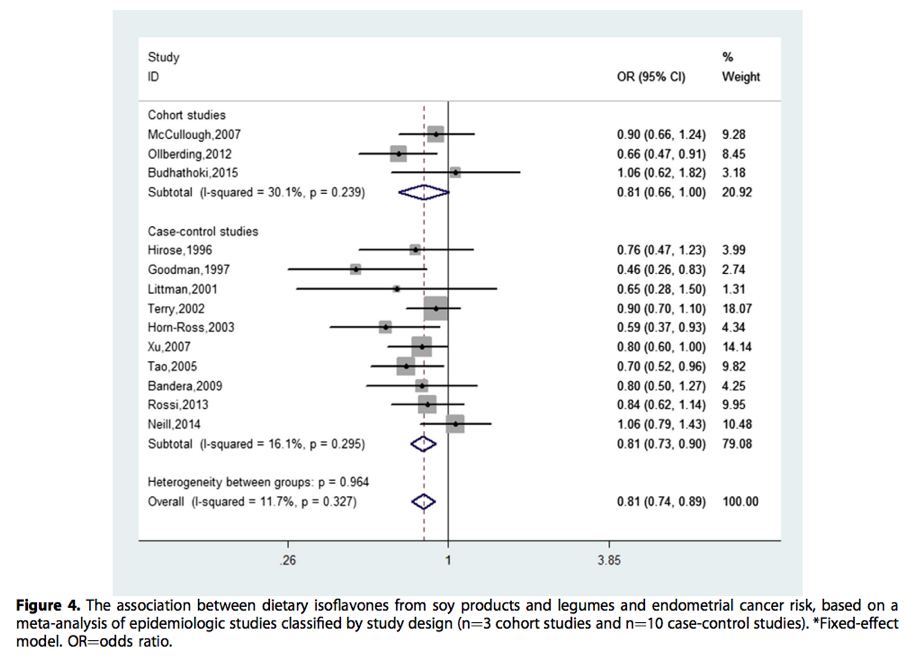

To close off this portion of the discussion, a more recent 2018 meta-analysis carried out to discover the effect of soy and legume isoflavones on endometrial cancer risk reached a conclusion not unlike that of the previous meta. While this analysis included 3 additional studies (for a total of 10 case-control and 3 prospective cohorts) the new studies disappointingly only considered a broad measure of legume consumption and not specifically soy intake. This note aside, when all the studies were pooled together it was shown that higher isoflavone intake from soy and other legumes appeared to significantly reduce the risk of endometrial cancer. Once again, when analyzing the case-control and prospective cohorts separately, only the former produced a significant result, although the top end of the odds ratio’s confidence interval for the latter sat directly at the null (1.00), as seen below¹⁷.

Finally, although this has been repeated almost ad nauseam, it still deserves mentioning; two of the three prospective cohorts (with the exception being Budhathoki et al., that actually had considerably high intakes in the lowest and highest quantiles) had very low, and a limited range of soy or legume intake, which would seriously impair the capability of the analysis to detect any effect on risk. Once again, the authors note this limitation and encourage further research in the area considering the consistent suggestion of benefit in other cohorts.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Alongside these cancers, it is also curiously suggested by a variety of health professionals that those with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) should avoid soy. PCOS is a disorder that can cause an array of reproductive and metabolic abnormalities, resulting from hyperandrogenism (the production of excess androgens usually resulting from a disruption of normal ovarian or adrenal function)¹⁸. Not unlike the previous conditions, there seems to be a concern with soy consumption in lieu of its phytoestrogen content and the role of hormonal imbalance in the pathology of PCOS. However, just considering the previous discussions on the minimal or non-existent changes in hormones following the ingestion of soy or its isoflavones (even in quantities well above those achieved through populations with high consumption of soy foods), and the lack of harmful effect or even benefit seen in these other chronic diseases; it should be fairly clear that such concerns are likely overzealous at best. Indeed, upon consulting the available evidence pertinent to this topic, these concerns are shown to be far-fetched, and may even be preventing beneficial effects that could accompany increased soy food/isoflavone consumption.

Since the late 2000s, a handful of interventional trials have sought to elucidate the effects of soy foods or their isoflavones on various biomarkers of metabolic, cardiovascular, and hormonal status of women diagnosed with PCOS. Funnily enough, the trials were carried out under the impression these foods/isoflavones could actually serve as potential adjunct therapies to traditional PCOS treatment. Although the effects observed varied slightly between these trials, a few of them were consistent and indicated a beneficial impact of soy foods or isoflavones on prognostic metabolic, cardiovascular, and hormonal biomarkers.

One of the first attempts to evaluate the effect of soy isoflavones (more specifically, genistein) on certain metabolic and cardiovascular outcomes in women with PCOS was a trial carried out by Romualdi et al. in 2008. This pilot trial enrolled 12 Caucasian, obese, hyperinsulinemic, and dyslipidemic women with a mean age of 23, who subsequently received 36 mg/d of genistein for 6 months. At the end of the trial, the only major changes appeared to be significant reductions in total and LDL cholesterol, with trends suggesting an improvement in HDL cholesterol and triglycerides. Despite being limited to these changes, the authors concluded that the isoflavone genistein may be a worthwhile addition to standard therapy for PCOS, especially in those with lipid profiles that could increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes¹⁹.

A few years later in 2011, results were published from a larger “quasi-randomized” placebo-controlled trial involving 146 women with PCOS. This trial mainly set out to gather further evidence either confirming or denying the effects observed previously by providing the women with either 36 mg/day of genistein or a matched placebo for 3 months. Results indicated that genistein supplementation caused significant reductions in luteinizing hormone, triglycerides, LDL, DHEAS, and testosterone, however only the difference in LDL was significant between placebo and treatment groups. Furthermore, the lack of randomization, documentation of baseline weight/BMI, and failure to consider differences in other biomarkers should cause one to exercise caution against drawing strong conclusions from these results despite them being consistent with those from the past²⁰.

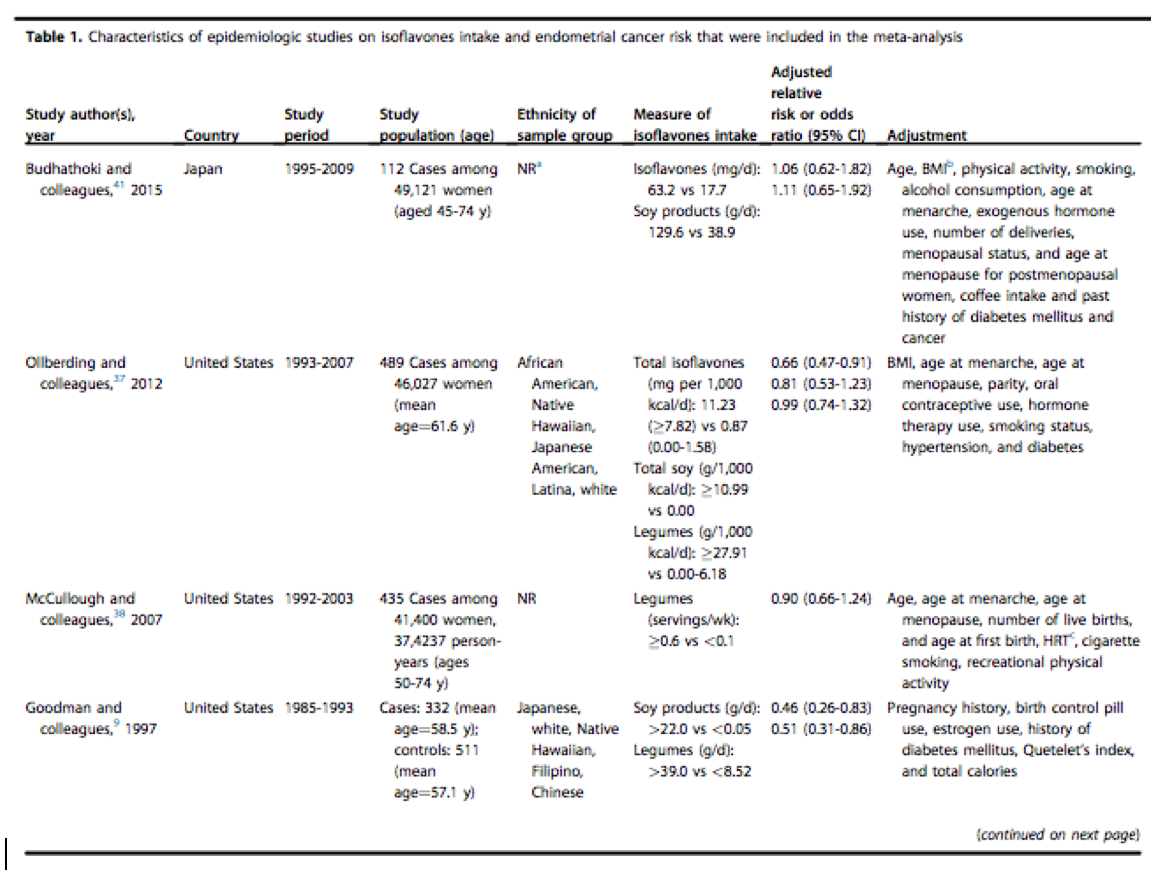

Next, a much higher quality randomized, placebo-controlled trial on 70 women aged 18–40 and diagnosed with PCOS was carried out in 2016 to determine the effects that supplementing 50 mg/day of soy isoflavones had on various health-related biomarkers. After 3 months, the women in the intervention group experienced significant reductions in insulin, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance/beta cell function (HOMA-IR/B), total testosterone, triglycerides, very low density lipoproteins (VLDL), nitric oxide (NO), and malondialdehyde (MDA), and increases in SHBG and plasma total glutathione (GSH). Interestingly, no significant changes in LDL akin to those in the previous trials were observed. That said, it is important to note that the mean baseline LDL values in the groups here were far lower than those of the other studies. The majority of individuals had values within the normal reference range, and therefore such a lack of effect could almost certainly be related to this distinction. Although researchers commented that they lacked the funding required to employ the most accurate methods of testing for certain biomarker measurements, they still emphasized that their findings suggest soy isoflavones exert multiple positive effects on markers of insulin resistance, hormonal status, triglycerides, and oxidative stress²¹.

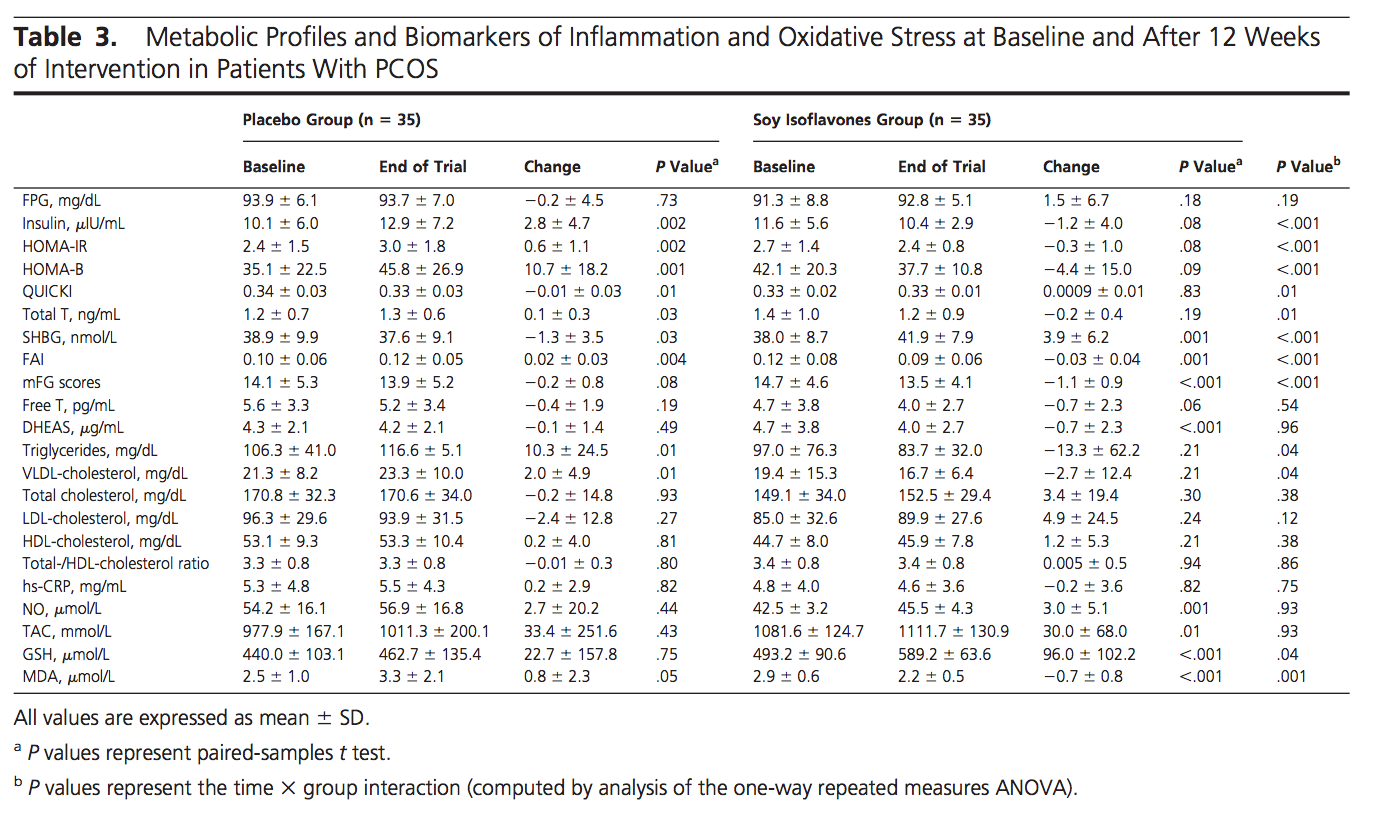

Recently, a 2018 randomized controlled trial on 60 women (mean age of 25) with PCOS was conducted to assess the impact of an 8-week dietary intervention containing 35% of total protein from textured soy protein on various clinical markers related to health status. Changes in these values were compared to those observed in a control group consuming an isocaloric and isonitrogenous diet containing only animal and other non-soy vegetable proteins. Remarkably, subjects in the test diet group had significantly reduced weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference (WC), hip circumference (HC), fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total testosterone, insulin, HOMA-IR, triglycerides, VLDL-cholesterol, and MDA, alongside significantly increased quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index (QUICKI), NO, and GSH compared to the control group. Similar to the previous trial, no significant change in LDL between groups was observed, again likely due to the very low baseline values. Nonetheless, given these results, the authors remarked that the test diet “may have an advantageous therapeutic potential for patients with PCOS”²².

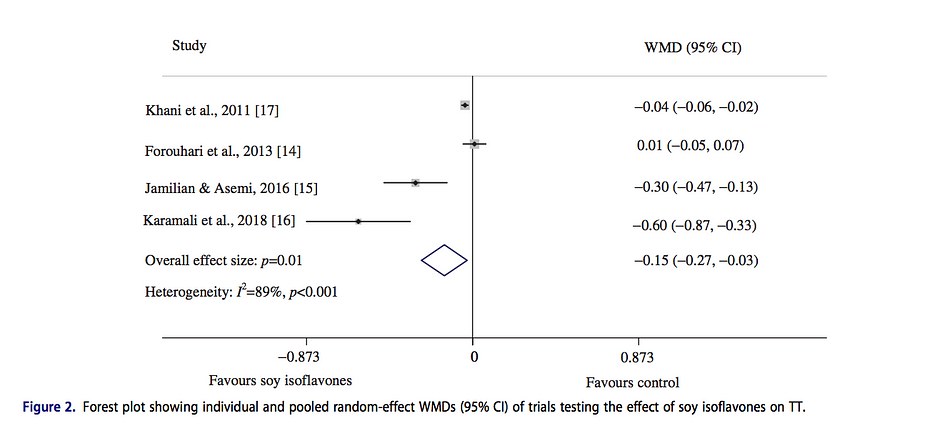

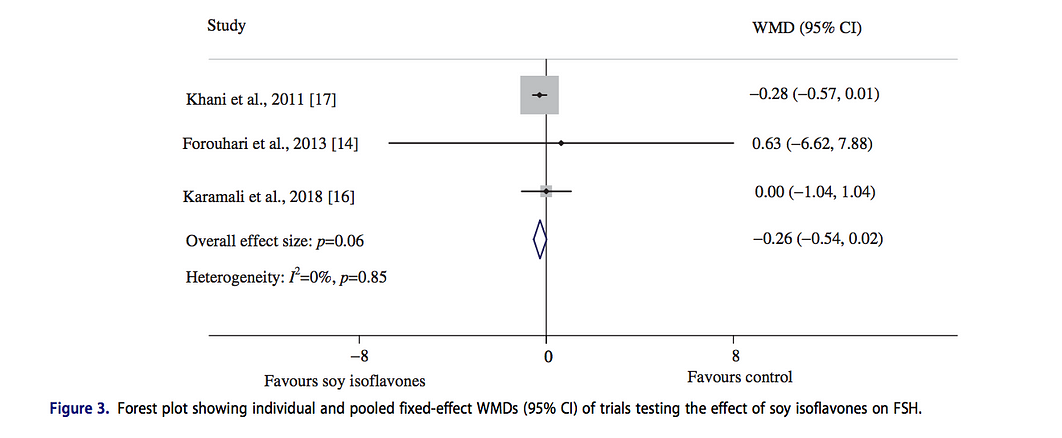

Lastly, just within the past year, a meta-analysis was carried out on RCTs containing interventions with soy isoflavones in women with PCOS. The purpose was to reveal the effect of these compounds on total testosterone and follicle-stimulating hormone, of particular interest in this demographic seeing that the pathophysiology of PCOS includes increased plasma androgen (especially testosterone) concentrations and an increased ratio of luteinizing hormone to follicle-stimulating hormone. Interestingly, differing slightly from the trials already discussed, soy isoflavones seemed to significantly decrease serum total testosterone and just barely fell short of significantly decreasing serum follicle-stimulating hormone concentrations in these women.

In accordance with the small number of trials included, the authors noted the results should be interpreted cautiously preceding the completion of additional trials²³. That being said, it’s evident that the current evidence does point towards these compounds exerting positive effects in the context of women with PCOS.

Weighing the evidence from the randomized-controlled trials and meta-analysis on this topic, it is apparent that if anything the regular incorporation of soy or its isoflavones into the diet of women with PCOS results in positive effects on typical metabolic, cardiovascular, and inflammatory aberrations associated with the condition. Given the lack of any meaningful indication of harmful effects and the potential benefits seen in these trials, recommendations from health professionals should actually be that it may be worth including, not excluding, soy foods in the diet of women who have PCOS.

Pre, Peri, and Postmenopausal Symptoms

Moving on to claims specific to the effect of soy intake on pre, peri, and postmenstrual syndrome symptom severity, and endometriosis risk, the previous trend continues. Human-based evidence either does not indicate harmful effects of soy, or implies a likely positive effect. Of these three, the impact of soy/soy isoflavones on menopausal symptoms has been researched to the greatest extent, so therefore the relationship with these two will be covered first.

There are a handful of meta-analyses dating back to the early 2000s observing the effect of soy/soy isoflavone intake on perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms, many of which focus on one of the most prevalent and bothersome symptoms; hot flashes (or “flushes”, depending on the location). A 2004 meta-analysis including 10 randomized controlled trials involving soy/soy preparations for the treatment of perimenopausal symptoms demonstrated mixed results, but hinted that soy may very well elicit a positive effect on these symptoms. The authors declared that due to the heterogeneity of the trials, it proved difficult to draw a definitive conclusion, with four of the ten showing significant positive effects, and one of the remaining 6 only trending towards significance. Alas, since there were no major adverse events observed, and the prevalence of adverse events overall was equal or lower in the soy intervention groups when compared to placebo, they encouraged further research to be carried out to establish the true effect²⁴.

Following the completion of additional trials including soy isoflavones, a 2012 meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials was carried out to determine their effect specifically on hot flash frequency and severity. The analysis included a total of 17 trials, 13 observing the effect on hot flash frequency, and 9 on severity. Results revealed that soy isoflavone supplementation appeared to significantly reduce the frequency and severity of hot flashes compared to placebo.

The authors also noted that supplements providing over 18.8 mg of genistein per day (the median of all the trials) were more effective in reducing frequency than lower doses and that longer trials appeared to be accompanied by stronger effects.

This seemed to suggest that genistein may be the main driver of the observed benefits, and there appears to be a time and dose-dependent response. Although they remarked that future research could help to elucidate other reasons for heterogeneity between trials, they concluded that based upon the studies evaluated, soy isoflavones appear to be a safe and viable treatment for the relief of menopause-related hot flashes, especially in women who do not want to use hormone therapy²⁵.

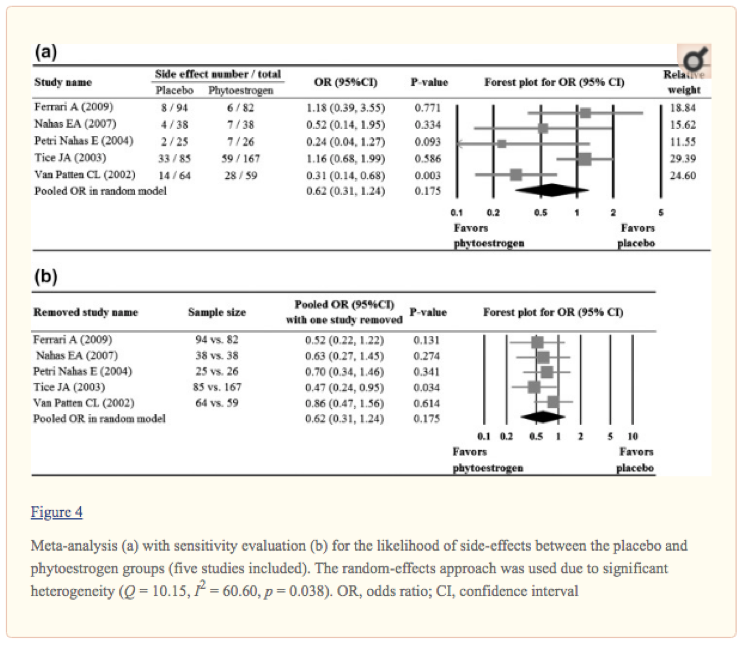

Another meta-analysis carried out in 2015 provides additional support for the efficacy of soy isoflavones in reducing hot flash frequency. While no effect on the Kupperman Index (a score derived from summing ratings for 11 symptoms common during menopause) was seen with isoflavone supplementation, significant reductions in hot flash frequency were observed once again. Though this meta only included 10 trials for hot flashes, 7 of these 10 were not included in the previous meta-analysis by Taku et al, making this data set comprised mostly of unique trials. Furthermore, the authors also carried out a comparison of side effect frequency within the intervention and placebo groups where possible, only to reveal no significant differences between the two.

Consequently, the authors concluded that isoflavones reduced hot flash frequency with no difference in side effect frequency compared to placebo, making them a potentially beneficial therapy for menopausal women experiencing regular hot flashes²⁶.

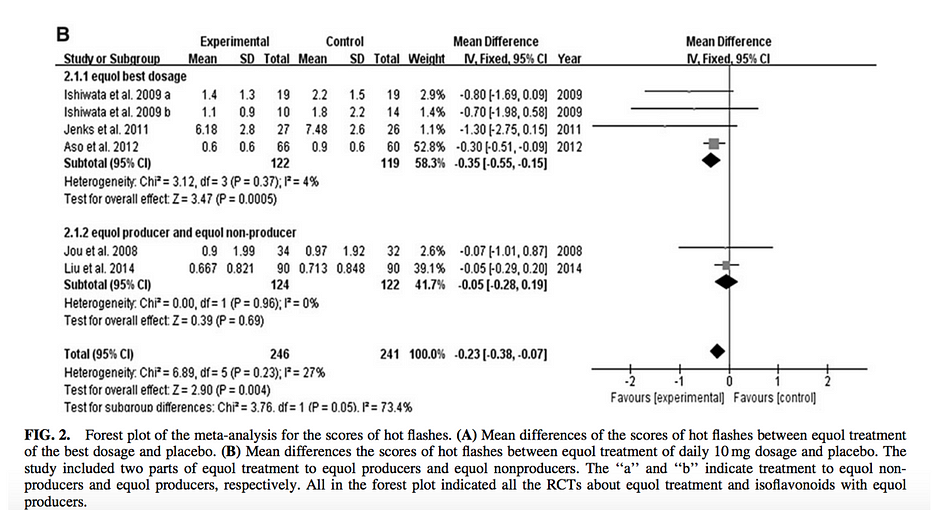

Finally, instead of focusing on the isoflavones found directly in soy, a 2018 meta-analysis set out to determine the impact of equol supplementation (as mentioned earlier, equol is a metabolite of daidzein, the major isoflavone in soy foods) on hot flash frequency, and if there was any difference in the effect seen in equol producers (those capable of producing the metabolite) and equol non-producers. The analysis included 5 randomized controlled trials of equol or isoflavone supplementation in perimenopausal or menopausal women and demonstrated that supplementation produced significant reductions in hot flash frequency compared to placebo.

Interestingly, the authors also noted that the effect (although based on very limited data) in equol producers was of a lesser magnitude. They hypothesized this could be due to the fact that producers with higher baseline dietary intake of daidzein already produce appreciable amounts of equol via its metabolism, enough to prevent further supplementation from having a measurable impact on hot flash frequency. In spite of this, they still emphasized the value of additional research on the subject²⁷.

Henceforth, based upon the collective findings of these meta-analyses, any concern regarding adverse effects of soy foods or isoflavones with respect to their impact on perimenopausal and menopausal symptoms, especially hot flash frequency and severity, are without much merit. Conversely, though not without area for improvement, the literature actually suggests they may be beneficial for hot flashes. It appears that at the worst they do not significantly impact other specific symptoms of perimenopause and menopause, and that they certainly do not cause more severe or total adverse events than placebo.

Premenopausal Symptoms and Endometriosis

As far as soy food/isoflavones’ impact on premenopausal symptom severity and endometriosis risk, quality human-based data is relatively scarce. There are only a select few cross-sectional studies, cohorts, and controlled trials pertinent to the conditions, and many included observations specific to multiple stages of menopause. That said, the literature available does not signal any cause for concern, and remarkably consistent with previous outcomes, instead hints at a positive or neutral effect of soy foods/isoflavones.

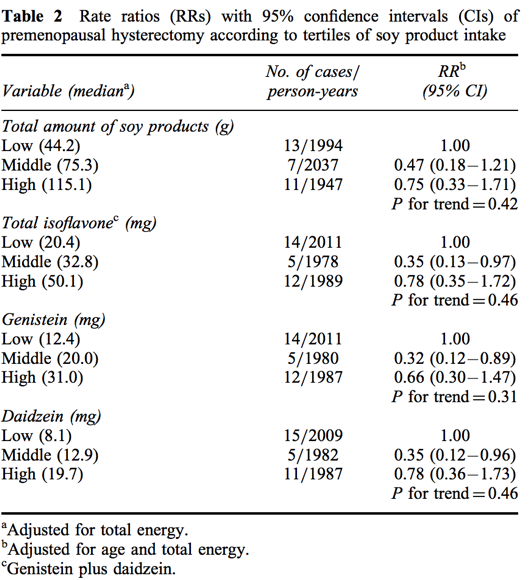

Concerning endometriosis, a condition in which the endometrium (the tissue normally lining the inside of the uterus) grows outside of its normal bounds, there does not even appear to be any research directly observing its relationship with soy food intake. This is unfortunate, but unsurprising given that information pertinent to the diagnosis, prognosis, pathophysiology, and other characteristics of the condition is still being elucidated. However, there is one prospective cohort observing the relationship between soy food intake and pre-menopausal hysterectomy (of which endometriosis is a common indication). This cohort included 1172 Japanese women aged 35–54 that were followed for 6 years. Funnily enough, though the authors hypothesized soy may exert negative effects leading to increased risk of hysterectomy (as with previous claims, based solely on the fact that estrogen plays a role in its pathophysiology and soy contains phytoestrogens), the results revealed that there were no significant differences in the incidence of premenopausal hysterectomy across tertiles of soy intake, and a significantly lower incidence in the second tertile of isoflavone intake, despite the trend for a dose-response not reaching significance.

Accordingly, they ended up concluding that the opposite of their original hypothesis may be true; higher soy food intake might decrease the risk of diagnoses (including endometriosis) that lead to the need for a premenopausal hysterectomy²⁸. Although this data does not signify any reason for alarm, it’s fairly evident that of everything discussed so far, the relationship between soy consumption (among most other dietary components/lifestyle habits) and endometriosis requires additional research the most.

The effect of soy consumption on pre-menopausal syndrome symptoms has been researched much more than its effect on endometriosis risk, but the evidence is also of lower quality and mostly comes from cross-sectional studies. Fortunately, in addition to these, there is at least one controlled trial on soy isoflavones’ influence on PMS symptoms.

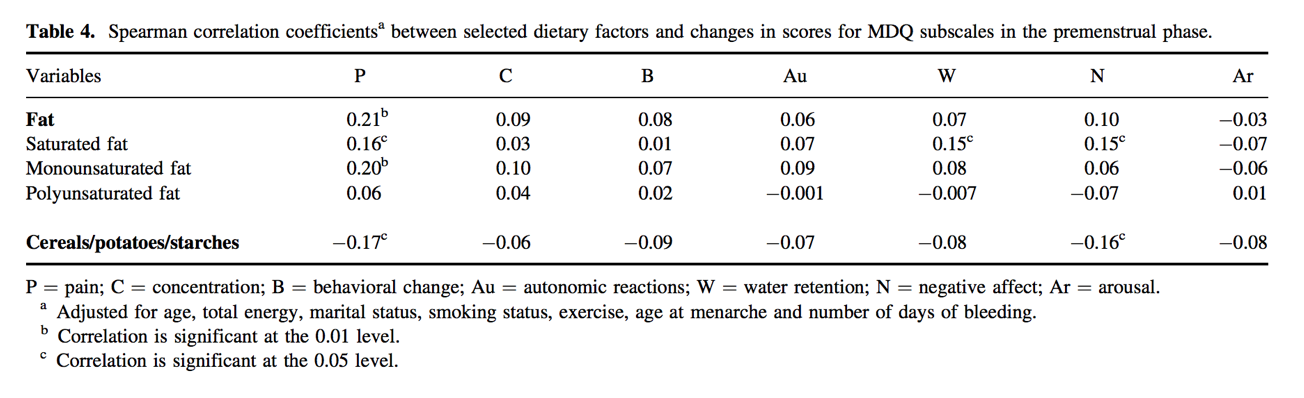

The earliest cross-sectional study on this topic was carried out in 2004, with the intention of discovering how soy, fat intake, and other dietary factors affected premenstrual symptoms among 189 Japanese women aged 19 to 34. In order to do this, researchers sought to determine if there were any significant correlations with different dietary components and changes in Moos Menstrual Distress Questionnaire (MMQ) scores and sub-scores (which assesses the severity of menstrual symptoms). Results highlighted a few dietary factors that did have significant correlations with MMQ scores; intakes of total fat, saturated fat, monounsaturated fat, and cereals/potatoes/starches. Total and monounsaturated fat intake correlated with increased pain sub-scores, while saturated fat correlated with increased pain, water retention, and negative affect scores, and cereals/potatoes/starches with decreased pain and negative affect scores. Soy food and isoflavone intakes displayed no significant correlation with any of the sub-scores.

Considering their findings, authors remarked that high intake of fat (especially saturated and monounsaturated) and low intake of cereals/potatoes/starches may be associated with increased PMS symptoms, but not soy foods, and encouraged future research on the subject²⁹.

In the following year, the same group of researchers carried out another cross-sectional study on 276 Japanese women aged 19–24, this time to observe the potential effect of soy, fat, and dietary fiber on the severity of menstrual pain. The only notable finding was that there was a small but significant reduction in menstrual pain associated with higher dietary fiber intake. A few other dietary components trended towards having associations with menstrual pain, though none were significant.

Considering their findings, the authors commented that despite the fact there were only small differences in fiber intake across levels of menstrual pain, it may have positive effects on this type of pain. They again urged the importance of further research on this topic, especially with respect to potential beneficial implications of certain dietary components on common and bothersome symptoms of pre-menopausal syndrome symptoms, including but not limited to menstrual pain/dysmenorrhea³⁰.

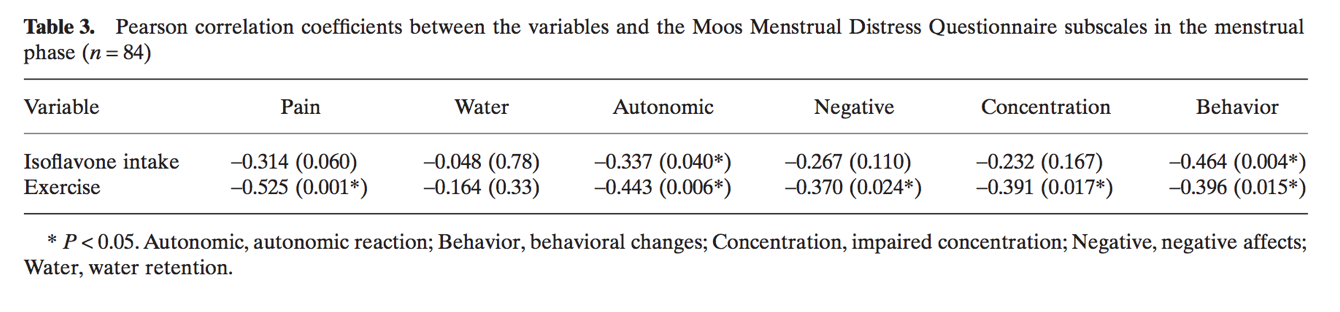

In 2006, another group of researchers conducted a cross-sectional study on 84 Korean women aged 28–40 living in the US in order to elucidate the impact that soy isoflavone intake may have on premenstrual and menstrual symptoms. Like previous research, they used MDQ scores to quantify symptom severity. In their analysis, soy isoflavones were found to have significant negative correlations with autonomic and behavioral symptom subscales of the MDQ within the menstrual phase; with a stepwise regression suggesting that 11.4% of the variation in menopause symptom severity was accounted for by differences in isoflavone intake. Such findings were confined to women in the menstrual phase, with no significant differences in symptom scores during pre and postmenopause being found.

In alignment with these findings, they declared: “In terms of this study, further research should be focused on the mode of action of soy isoflavones and their responsibility for the positive effects, such as autonomic reactions, behavioral changes, and other effects on menstruation phenomena”³¹.

The following year, a cross-sectional study of 245 women aged 19–49 carried out in Korea attempted to determine how soy food/isoflavone consumption affect common symptoms involved with the various stages of the menstrual cycle, also using MDQ scores. Alike the study from the previous year, they observed a handful of significant changes in some menstrual symptom scores, as well as in post-menstrual symptom scores, but of varying direction and strength across tertiles of isoflavone intake. The most consistent finding was that women in the second, or “medium consumption” group, appeared to have the best symptom scores, in many instances significantly lower than those in both the low and high consumption groups. Furthermore, there were no significant increases in any MDQ sub-scores when comparing low to high intake groups, indicating no exacerbation of symptoms among those with the greatest soy isoflavone intake.

Overall, the researcher’s findings displayed that higher soy isoflavone consumption may have had positive effects on certain peri and postmenopausal symptoms, but that they didn’t significantly impact premenopausal symptoms. As such, they closed with the comment that further research in this area is warranted and of much interest.³²

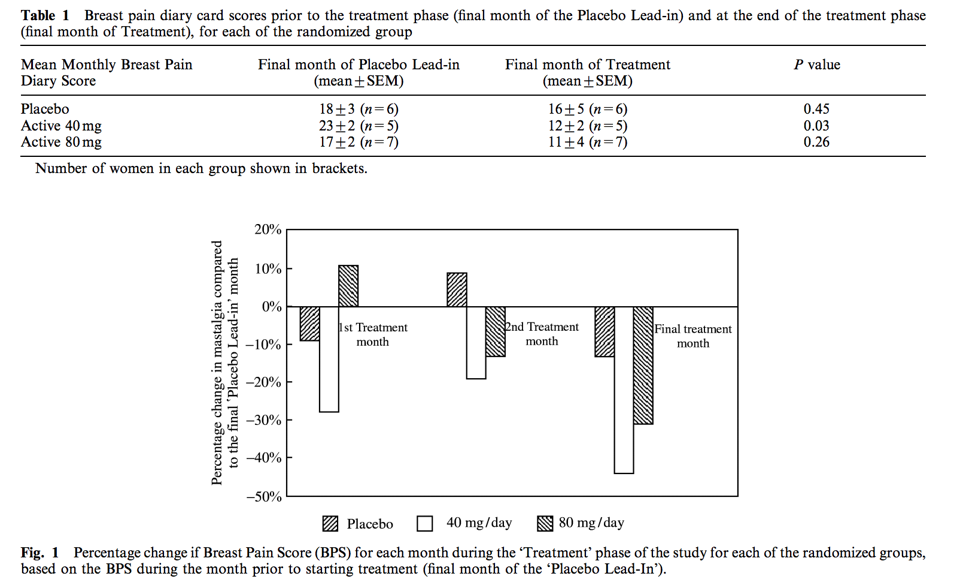

The interest in this topic and the fairly consistent positive findings have spurred a few randomized controlled trials involving soy isoflavone interventions for the treatment of various premenopausal syndrome symptoms. In 2002, a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial was carried out on 18 premenopausal women with cyclical mastalgia (breast pain) to ascertain how two different doses of isoflavones (including genistein and daidzein) affected the severity of their pain over the course of three months of treatment. Following treatment with 40 mg and 80 mg of isoflavones, 44% and 31% reductions in pain were observed, compared to only 13% in the placebo group (depicted below).

Since results hinted that there may be a potential reduction in the severity of cyclical mastalgia with isoflavone supplementation, and there were no severe adverse events recorded, authors enthusiastically stated that they could serve as a valuable tool to standard therapy for this condition, especially given the frequency of side effects with current treatment options.³³

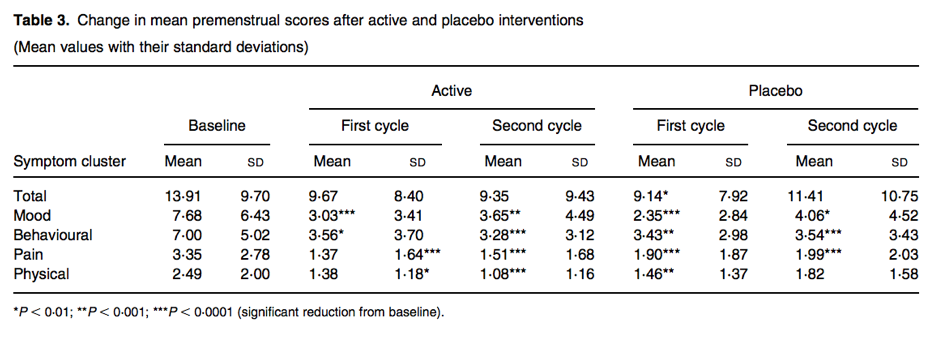

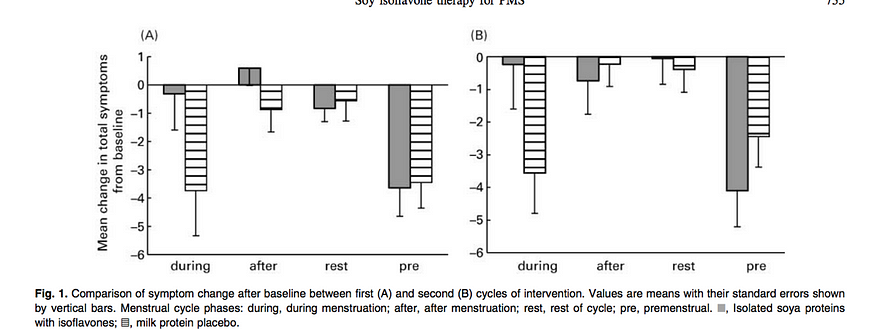

A few years later, another group of researchers carried out a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial on 23 premenopausal women in order to discover if isolated soy protein containing a specified dose of soy isoflavones (68 mg/day) would have any effects on premenopausal syndrome symptoms. After two months of treatment, there were quite a few significant decreases in the severity of specific symptoms, although many were seen in both the placebo and active treatment group, and differences between the two remained insignificant. That said, the difference between the reductions in the subset of physical premenstrual symptoms just barely fell short of significance (in favor of active treatment). Furthermore, reductions in the severity of the individual symptoms of cramps and swelling in the active treatment groups were significantly greater than those in placebo groups. As the authors briefly mention, this is particularly interesting given that these somatic symptoms are even less prone to potential psychological influences (and therefore placebo effects) in comparison to mood and behavioral symptoms.

In a few final remarks, the authors mention that their study provides support for the notion that soy isoflavones may exert positive effects on some premenopausal syndrome symptoms. They also exclaim that while significant differences between the effects of active treatment and placebo on total symptom severity were not found, improvements in somatic symptoms (swelling, headaches, breast tenderness, and cramps) were. Lastly, they comment that it is unclear whether these improvements are specific to isoflavone treatment, and that there is even a possibility any reductions in psychological symptoms are overshadowed by a strong placebo effect, but admit that further research with longer intervention periods is needed to confirm or deny this theory.³⁴

As a whole, although many cross-sectional studies and a few randomized controlled trials throughout the 2000s insinuated that there was either no effect or a positive effect, of soy food and/or isoflavones consumption on some common premenopausal symptoms; more research is needed to strongly confirm these findings. Unfortunately, there has been a dearth of research (at least that which is easily accessible) on the subject since the publication of these studies, denoting this is certainly a valuable area for future researchers to focus their efforts on in order to help unravel the full picture. Regardless, based upon the available evidence there is no valid basis for claiming soy foods or isoflavones actually increase PMS symptomatology, and if anything, one could suggest it’s exceedingly more likely the opposite is true.

Other Common Chronic Diseases

Concerns specific to all of these specific conditions aside, there are also a lot of general claims made about supposedly inherent harmful effects of soy foods on health. The vague nature of these makes it difficult to address them directly, but thankfully the egregious amount of research available on soy and a wide variety of conditions reveals their remarkable lack of validity, especially given that the evidence shows soy has positive or neutral impacts on virtually all major health outcomes that have been studied. While it would be near impossible to include all of this research, the following discussion will serve to cover the findings from a fairly large amount.

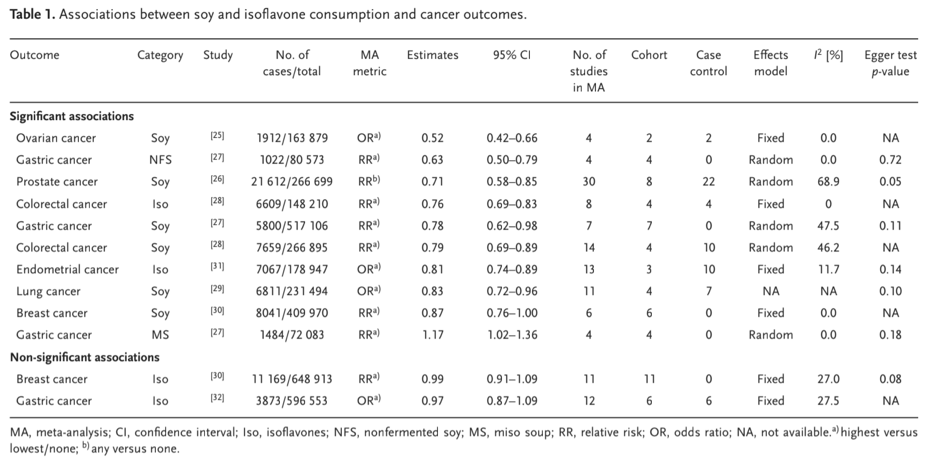

Especially in the past decade, there have been numerous large meta-analyses on the effect of soy foods, isoflavones, or protein on the risk of many common chronic diseases, including but not limited to diabetes, cardiovascular disease, prostate cancer, gastric cancer, and other cancers, in addition to all-cause mortality. Contrary to what many individuals may claim, the body of evidence shows that the risks of contracting these diseases are not increased and that many may actually be decreased with a higher intake of specific soy foods³⁵-⁴⁰. Most impressive are the results from a recent, incredibly comprehensive umbrella review of meta-analyses on soy foods and health outcomes. The review included 114 separate meta-analyses encompassing millions of individuals across a variety of countries and demographics, all conducted to characterize the influence of certain soy foods on the risk of 43 unique health outcomes. Remarkably, of all the outcomes considered, there was only a single case where a soy-based food negatively influenced the risk of a condition; higher miso soup consumption increased the risk of gastric cancer. However, as rightfully noted by the authors:

High intake of miso soup (1–5 cups per day) in male might increase the risk of gastric cancer.[27] As one kind of fermented soy food, miso soup is the most basic soup in Japan, the concentration of salt in miso soup is 0.5–1.2%.[96] In 2004, Tsugane and colleagues conducted a population-based prospective study of 18 684 men and 20 381 women aged 40–59 years in Japan, they found a dose-dependent increased risks of gastric cancer with the intake of highly salted foods, for example, pickled vegetables, miso soup, and dried or salted fish in men.[96]…In addition, salt intake is known to cause gastritis, and it enhances the carcinogenic effects of known gastric carcinogens, for example, N-methyl-N-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine (MNNG) when co-administered in experimental studies with rats.[99,100] Furthermore, It has been suggested that salt intake is strongly associated with intestinal metaplasia and potentiates the effects of carcinogens.[101]

Taking this into account, it appears likely that the sole harmful association for soy food (miso/miso soup) identified in this umbrella review is not even intrinsic to soy itself, but the processing and additional ingredients present specifically within one specific form. This is only further emphasized by the fact that it was found higher consumption of non-fermented soy (such as tofu, soy milk, soybeans, soy protein, etc.) was associated with a significantly lower risk of gastric cancer, based on data from over 5 times as many participants than for the relationship seen with miso soup. Even more astonishing than the fact that only this one significant harmful association was observed was the number of positive effects higher soy food/isoflavone consumption had on a large collection of health outcomes, as clearly depicted in the publication’s tables.

Although all-cause mortality just fell short of being significantly reduced with higher consumption of soy foods (important to note is that this analysis was based on only a few publications and had one of the smallest samples, resulting in far less power to detect an effect), higher intake did significantly improve multiple cancer, cardiovascular disease, gynecological, metabolic, musculoskeletal, endocrine, neurological, and renal outcomes. The frequency in which higher soy food/isoflavone intake appeared to exert positive effects on this collection of diseases outweighed that of neutral effects by nothing short of an extraordinary margin⁴¹. As such, this umbrella review only serves to dismantle the common remarks about soy being unhealthy to an even greater degree.

GMO Soy: Cause for Concern?

While the enormous amount of data showing soy foods either have neutral or positive effects on a variety of health outcomes should preclude most assertions about this from the outset; another common concern is that a large proportion of soy crops are considered GMOs (genetically modified organisms), and therefore consumption of them is somehow harmful to humans. The fact that this concern still persists (and is not at all unique to soy) is very unfortunate as it is rooted in many misconceptions, is not supported by quality human-based evidence, and frequently instills unnecessary fears about health-promoting foods in a large number of consumers. The photo preceding this section only serves to emphasize the kind of negative connotations associated with what is a far simpler and safer process than assumed by said consumers.

What is a GMO?

First, it is essential to define exactly what a genetically modified organism is in order to establish whether or not there is even a reason to be worried about them. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does an excellent job providing a simple explanation of what the process of genetic modification entails, and even gives a detailed description of a direct application on their page regarding the science and history of food modification processes (accessible here). They state the following:

“GMO” (genetically modified organism) has become the common term consumers and popular media use to describe foods that have been created through genetic engineering. Genetic engineering is a process that involves:

– Identifying the genetic information — or “gene” — that gives an organism (plant, animal, or microorganism) a desired trait

– Copying that information from the organism that has the trait

– Inserting that information into the DNA of another organism

– Then growing the new organism

Additionally, they describe the importance and appeal of advancements in genetic modification of crops; emphasizing that they allow for far more precise and rapid introduction of desired traits that may improve crop resilience, improve yield, texture, taste, and many other characteristics in comparison to the tradition cross-breeding process previously used to impart the same effects. A lot of these changes can be used to combat major problems specific to crop sustainability and quality, and offer solutions to unique food supply and nutrition-related challenges pertinent to promoting and maintaining public health. In summary, genetic modification allows for scientists to expedite the development of preferred crop traits that typically occurs at a substantially slower pace through cross-breeding of different species. At this point it should be easily inferred, but genetic modification of crops is completely safe (as mentioned by the FDA, has been demonstrated numerous times), which is unsurprising given the process mimics standard cross-breeding and results in the same end product, only in a timelier fashion.

Prevalence of GMO Soy

While genetic modification of crops doesn’t inherently impose any sort of health threat to individuals consuming them, this point is almost completely irrelevant with respect to soy commonly sold for human consumption anyway. This becomes fairly evident upon reading the United States Department of Agriculture’s coexistence fact sheet on soybean products; which states the following:

Soybean farmers in the United States have the choice of planting biotech, organic or conventional seeds, and make their choice based on production methods or access to direct end-use markets. Of those 76 million acres planted, 94 percent (or more than 70 million acres) of the seeds were biotech…

Just over 70 percent of the soybeans grown in the United States are used for animal feed, with poultry being the number one livestock sector consuming soybeans, followed by hogs, dairy, beef and aquaculture. The second largest market for U.S. soybeans is for production of foods for human consumption, like salad oil or frying oil, which uses about 15 percent of U.S. soybeans…

A small number of acres in the United States are dedicated to growing organic soybeans. These soybeans are divided into two types: food-grade and feed-grade, and receive premium prices. Organic food-grade soybeans are used in food products like tofu, tempeh or soymilk, and can be produced in the United States or abroad. Organic feed-grade soybeans are used to develop organic livestock feed, which is required to be fed to livestock by producers who raise certified organic meat.

This distribution is gorgeously depicted by a recent infographic found in Our World In Data’s recent article on soy, which also covers common misconceptions related to ostensible environmental harm resulting from the growth of soybeans for human food production.

So, in reality, not only is a massive proportion of genetically modified (or “biotech”) soy grown specifically for animal feed and oil production; the intact soy foods like tofu, tempeh, and soymilk that are associated with a myriad of health benefits prioritize organic food-grade beans, which aren’t even GMOs in the first place (made very apparent by the ubiquitous “non-GMO” labeling found on these products). Considering these details, there is a lack of justification for any declarations that most soy grown for human consumption is even genetically modified, never mind that this supposedly makes them harmful to health.

The Big Picture

In summary, the totality of the current evidence suggests that consumption of soy, its isoflavones, or soy protein does not significantly impact concentrations of hormones (most notably testosterone) in men, and could possibly cause a small decrease in LH/FSH in pre-menopausal women (although not in an analysis of higher quality studies), as well as a non-significant increase of total estradiol in postmenopausal women. Regardless of the effects (or lack thereof) on hormone concentrations, soy has no negative effects on the risk of any conditions or symptoms in women attributed to abnormalities in hormone concentrations, such as breast and gynecological cancer, pre-, peri-, and post-menopausal symptoms, endometriosis, and PCOS. Likewise, contrary to what is frequently claimed (and especially in the cases of breast cancer, gynecological cancers, and hot flashes in postmenopausal women), increased intake of soy foods actually appears to coincide with improved health outcomes of women. Although a few outcomes have very limited/low-quality data and require further investigation, preliminary results still point towards either neutral or promisingly positive effects.

In addition to these hormone-related conditions in women, an umbrella review of meta-analyses suggests that increased soy food or isoflavone intake decreases the risk of multiple common cancers and cardiovascular diseases, and also improves an assortment of metabolic, musculoskeletal, neurological, and renal health outcomes. A single harmful association was identified for miso soup, which was found to increase the risk of gastric cancer, despite non-fermented soy foods being associated with a strong, significant reduction in the same outcome. As eloquently noted by the authors, this discordance was likely due to the presence of high amounts of sodium in miso soup, a major known risk factor for gastric cancer, suggesting that it would certainly be wise to moderate intake of miso or miso-containing dishes. Lastly, the remaining outcomes (an impressively small amount given the total number investigated) identified a lack of an effect in accordance with higher soy and isoflavone intake.

Finally, the alarmingly common concerns surrounding GMO foods are overstated and not supported by human-based evidence. In strong contrast to the myriad of misconceptions surrounding genetically modified crops, overall the concept is fairly simple and mimics changes in DNA that otherwise result from a time-consuming series of repeated cross-breeding. By expediting these changes via the direct introduction of specific genes, genetic modification can confer highly valuable traits to crops that may improve their yield, nutrition, sustainability, pest resilience, and more. Henceforth, it’s very unfortunate there is such resistance towards these advancements in science given their widespread applicability and potential to address pressing issues surrounding agriculture. Funnily enough, despite the safety of genetically modified organisms, the majority of whole soy foods available for consumer purchase are actually made from non-GMO soybeans, making this concern almost completely inapplicable. Astonishingly, most of the GMO soybeans grown in the United States (over 85%) are used as either animal feed or for processed soy products such as oil and other soy-derived ingredients.

Factoring in the paucity of harmful effects of soy foods, the risk-reducing potential for a large variety of chronic diseases, and the lack of a basis for concerns regarding genetically modified soy (most of which isn’t even used for whole soy products), there is no valid reason aside from an allergy to discourage its consumption, and considering the benefits an individual may reap, to do so could almost be considered just short of criminal.

If you have enjoyed this article, please consider supporting the site by donating here and subscribing to our email list below (we don’t spam!).

SUBSCRIBE TO EMAIL LIST

References:

- Siepmann, T., Roofeh, J., Kiefer, F. W., & Edelson, D. G. (2011). Hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction associated with soy product consumption. Nutrition, 27(7–8), 859–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2010.10.018

- Martinez, J., & Lewi, J. E. (2008). An Unusual Case of Gynecomastia Associated with Soy Product Consumption. Endocrine Practice, 14(4), 415–418. https://doi.org/10.4158/ep.14.4.415

- Viggiani, M. T., Polimeno, L., Di Leo, A., & Barone, M. (2019). Phytoestrogens: Dietary Intake, Bioavailability, and Protective Mechanisms against Colorectal Neoproliferative Lesions. Nutrients, 11(8), 1709. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081709

- Hooper, L., Ryder, J. J., Kurzer, M. S., Lampe, J. W., Messina, M. J., Phipps, W. R., & Cassidy, A. (2009). Effects of soy protein and isoflavones on circulating hormone concentrations in pre- and post-menopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Human reproduction update, 15(4), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmp010

- Hamilton-Reeves, J. M., Vazquez, G., Duval, S. J., Phipps, W. R., Kurzer, M. S., & Messina, M. J. (2010). Clinical studies show no effects of soy protein or isoflavones on reproductive hormones in men: results of a meta-analysis. Fertility and Sterility, 94(3), 997–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.038

- Reed, K. E., Camargo, J., Hamilton-Reeves, J., Kurzer, M., & Messina, M. (2021). Neither soy nor isoflavone intake affects male reproductive hormones: An expanded and updated meta-analysis of clinical studies. Reproductive Toxicology, 100, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2020.12.019

- Travis, R. C., & Key, T. J. (2003). Oestrogen exposure and breast cancer risk. Breast cancer research : BCR, 5(5), 239–247. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr628

- Rodriguez, A. C., Blanchard, Z., Maurer, K. A., & Gertz, J. (2019). Estrogen Signaling in Endometrial Cancer: a Key Oncogenic Pathway with Several Open Questions. Hormones & cancer, 10(2–3), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-019-0358-9

- Chen, M., Rao, Y., Zheng, Y., Wei, S., Li, Y., Guo, T., & Yin, P. (2014). Association between soy isoflavone intake and breast cancer risk for pre- and post-menopausal women: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. PloS one, 9(2), e89288. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089288

- Xie, Q., Chen, M. L., Qin, Y., Zhang, Q. Y., Xu, H. X., Zhou, Y., Mi, M. T., & Zhu, J. D. (2013). Isoflavone consumption and risk of breast cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition, 22(1), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.2013.22.1.16

- Wei, Y., Lv, J., Guo, Y., Bian, Z., Gao, M., Du, H., Yang, L., Chen, Y., Zhang, X., Wang, T., Chen, J., Chen, Z., Yu, C., Huo, D., Li, L., & China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group (2020). Soy intake and breast cancer risk: a prospective study of 300,000 Chinese women and a dose-response meta-analysis. European journal of epidemiology, 35(6), 567–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00585-4

- Chi, F., Wu, R., Zeng, Y.-C., Xing, R., Liu, Y., & Xu, Z.-G. (2013). Post-diagnosis Soy Food Intake and Breast Cancer Survival: A Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 14(4), 2407–2412. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.4.2407

- Qiu, S., & Jiang, C. (2018). Soy and isoflavones consumption and breast cancer survival and recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Nutrition, 58(8), 3079–3090. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1853-4

- Myung, S.-K., Ju, W., Choi, H. J., & Kim, S. C. (2009). Soy intake and risk of endocrine-related gynaecological cancer: a meta-analysis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 116(13), 1697–1705. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02322.x

- Qu, X.-L., Fang, Y., Zhang, M., & Zhang, Y.-Z. (2014). Phytoestrogen Intake and Risk of Ovarian Cancer: a Meta-Analysis of 10 Observational Studies. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 15(21), 9085–9091. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.21.9085

- Zhang, G. Q., Chen, J. L., Liu, Q., Zhang, Y., Zeng, H., & Zhao, Y. (2015). Soy Intake Is Associated With Lower Endometrial Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Medicine, 94(50), e2281. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000002281

- Zhong, X.-, Ge, J., Chen, S.-, Xiong, Y.-, Ma, S.-, & Chen, Q. (2018). Association between Dietary Isoflavones in Soy and Legumes and Endometrial Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 118(4), 637–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2016.09.036

- Clark, N. M., Podolski, A. J., Brooks, E. D., Chizen, D. R., Pierson, R. A., Lehotay, D. C., & Lujan, M. E. (2014). Prevalence of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Phenotypes Using Updated Criteria for Polycystic Ovarian Morphology: An Assessment of Over 100 Consecutive Women Self-reporting Features of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Reproductive sciences (Thousand Oaks, Calif.), 21(8), 1034–1043. https://doi.org/10.1177/1933719114522525

- Karamali, M., Kashanian, M., Alaeinasab, S., & Asemi, Z. (2018). The effect of dietary soy intake on weight loss, glycaemic control, lipid profiles and biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomised clinical trial. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 31(4), 533–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12545

- Khani, B., Mehrabian, F., Khalesi, E., & Eshraghi, A. (2011). Effect of soy phytoestrogen on metabolic and hormonal disturbance of women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of research in medical sciences : the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 16(3), 297–302.

- Jamilian, M., & Asemi, Z. (2016). The Effects of Soy Isoflavones on Metabolic Status of Patients With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 101(9), 3386–3394. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2016-1762

- Karamali, M., Kashanian, M., Alaeinasab, S., & Asemi, Z. (2018b). The effect of dietary soy intake on weight loss, glycaemic control, lipid profiles and biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a randomised clinical trial. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 31(4), 533–543. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12545

- Zilaee, M., Mansoori, A., Ahmad, H. S., Mohaghegh, S. M., Asadi, M., & Hormoznejad, R. (2020). The effects of soy isoflavones on total testosterone and follicle-stimulating hormone levels in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 25(4), 305–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2020.1761956

- Huntley, A. L., & Ernst, E. (2004). Soy for the treatment of perimenopausal symptoms — a systematic review. Maturitas, 47(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-5122(03)00221-4

- Taku, K., Melby, M. K., Kronenberg, F., Kurzer, M. S., & Messina, M. (2012). Extracted or synthesized soybean isoflavones reduce menopausal hot flash frequency and severity. Menopause, 19(7), 776–790. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3182410159

- Chen, M. N., Lin, C. C., & Liu, C. F. (2015). Efficacy of phytoestrogens for menopausal symptoms: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Climacteric : the journal of the International Menopause Society, 18(2), 260–269. https://doi.org/10.3109/13697137.2014.966241

- Daily, J. W., Ko, B.-S., Ryuk, J., Liu, M., Zhang, W., & Park, S. (2019). Equol Decreases Hot Flashes in Postmenopausal Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Journal of Medicinal Food, 22(2), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1089/jmf.2018.4265

- Nagata, C., Takatsuka, N., Kawakami, N., & Shimizu, H. (2001). Soy product intake and premenopausal hysterectomy in a follow-up study of Japanese women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 55(9), 773–777. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601223

- Nagata, C., Hirokawa, K., Shimizu, N., & Shimizu, H. (2004). Soy, fat and other dietary factors in relation to premenstrual symptoms in Japanese women. BJOG : an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, 111(6), 594–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00130.x

- Nagata, C., Hirokawa, K., Shimizu, N., & Shimizu, H. (2004). Associations of menstrual pain with intakes of soy, fat and dietary fiber in Japanese women. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 59(1), 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602042

- Kim, H. W., Kwon, M. K., Kim, N. S., & Reame, N. E. (2006). Intake of dietary soy isoflavones in relation to perimenstrual symptoms of Korean women living in the USA. Nursing and Health Sciences, 8(2), 108–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00270.x

- Kim, H. W., & Khil, J. M. (2007). A Study on Isoflavones Intake From Soy Foods and Perimenstrual Symptoms. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 37(3), 276. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2007.37.3.276

- Ingram, D. M., Hickling, C., West, L., Mahe, L. J., & Dunbar, P. M. (2002). A double-blind randomized controlled trial of isoflavones in the treatment of cyclical mastalgia. The Breast, 11(2), 170–174. https://doi.org/10.1054/brst.2001.0353

- Bryant, M., Cassidy, A., Hill, C., Powell, J., Talbot, D., & Dye, L. (2005). Effect of consumption of soy isoflavones on behavioural, somatic and affective symptoms in women with premenstrual syndrome. British Journal of Nutrition, 93(5), 731–739. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn20041396

- Weng, K.-G., & Yuan, Y.-L. (2017). Soy food intake and risk of gastric cancer. Medicine, 96(33), e7802. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000007802

- Yan, Z., Zhang, X., Li, C., Jiao, S., & Dong, W. (2017). Association between consumption of soy and risk of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis of observational studies. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 24(7), 735–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487316686441

- Li, W., Ruan, W., Peng, Y., & Wang, D. (2018). Soy and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 137, 190–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2018.01.010

- Tang, J., Wan, Y., Zhao, M., Zhong, H., Zheng, J.-S., & Feng, F. (2020). Legume and soy intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 111(3), 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqz338

- Applegate, C. C., Rowles, J. L., Ranard, K. M., Jeon, S., & Erdman, J. W. (2018). Soy Consumption and the Risk of Prostate Cancer: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 10(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10010040

- Nachvak, S. M., Moradi, S., Anjom-shoae, J., Rahmani, J., Nasiri, M., Maleki, V., & Sadeghi, O. (2019). Soy, Soy Isoflavones, and Protein Intake in Relation to Mortality from All Causes, Cancers, and Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 119(9), 1483–1500.e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2019.04.011

- Li, N., Wu, X., Zhuang, W., Xia, L., Chen, Y., Zhao, R., Yi, M., Wan, Q., Du, L., & Zhou, Y. (2019). Soy and Isoflavone Consumption and Multiple Health Outcomes: Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses of Observational Studies and Randomized Trials in Humans. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 64(4), 1900751. https://doi.org/10.1002/mnfr.201900751