The explanation for obesity is thought to be well understood: if you chronically eat more energy (calories) than you expend per day, you risk gaining body fat and becoming obese. Not many people would argue with that. So whether you ask your best friend for weight loss advice or seek it from public health authorities, the practical advice is the same: “you need to eat less and move more”.

Nevertheless, despite growing recognition of the problem, obesity rates are increasing worldwide and it remains a global epidemic. Many people are starting to ask questions as a result. Why is obesity so prevalent if the explanations and solutions are glaringly obvious? Is there some unknown or overlooked factor at play, or are people simply unable to maintain healthy behaviours?

Well, the scientific consensus still sits firmly with the latter explanation. Public adherence to dietary guidelines is inarguably poor and we now consume ~20% more calories per day than when obesity rates were low in the 1970s. Such increases in calorie intake can explain the bulk of changes in population body weight and, along with robust evidence from randomised controlled trials, there isn’t thought to be a need for anything other than energy balance to explain how shifts in body weight occur. This consensus, however, leads to rather deep questions about how obesity should be managed. If we accept that the primary explanation for obesity is low adherence to healthy eating behaviours, do we also accept that obesity is just a matter of personal responsibility? Must we reiterate that changing our actions is nothing more than sheer willpower? Or, do we begin to consider other possible explanations, such as how recent changes to our world have forcibly altered human behaviour, and that the blame doesn’t necessarily reside with the people suffering?

Needless to say these are complex questions that split opinions about how on earth we deal with the ever-rising obesity rates. Where the best answer lies is a matter of debate. Yet, underlying all of these questions is a more fundamental one that needs to be discussed if we wish to progress obesity conversations. That is, whether obesity, or at least eating behaviours that promote obesity, are indeed a personal choice and responsibility? I feel this is a question that often acts as a barrier in conversation. You’ll often find one debater say, “of course our eating behaviour is a choice; we choose what goes in our mouth and therefore we must change our ways”. Whereas the other debater will take the position that “our eating choices are influenced by numerous factors outside of our control; we must target those factors and not rely on people to will their way out of poor eating habits”. Agreeing on practical ways to manage obesity is difficult when we keep reaching this sticking point.

In this article, I want to illuminate the differences in opinion about eating behaviour and obesity as a matter of choice. Perhaps more interestingly, I also want to argue that answers to these questions rest as much with philosophy as they do with science.

“Eating Behaviour and Obesity Are Choices”

The conventional opinion among the public and even most health professionals is that eating behaviour is a personal choice. Therefore, as ‘eating less and moving more’ is a widely accepted method to prevent and treat obesity, then we, as conscious agents, can choose freely to act (or not) according to our desired body weight. If someone is eating a bag of cookies, they’ve made a conscious decision to eat a bag of cookies, knowing the benefits and consequences of their action, right? If so, we can say their choices (eating in excess) and the possible long-term effects of their choices (obesity) are just a matter of personal responsibility. There’s no need to intervene with such an individual other than reminding them to “eat less and move more”. It’s their choice to do so or not.

Indeed this view is widespread. It aligns with our conscious experience that we ultimately author our actions, regardless of whether we accept that external factors influence behaviour. We don’t see or feel ourselves being influenced and, at least in retrospect, we think that we freely control our actions. Even a systematic review of people living with obesity reported a powerful theme related to shame, blame, and worthlessness, indicating that sufferers of obesity themselves lack an alternative explanation for their actions outside of personal agency. Even more broadly as a society we congratulate those who successfully lose weight—seeing it as a sign of willpower and personal strength—while often frowning upon those struggling with their weight—seeing it as a reflection of laziness and low self-worth.

But while the surface-level nature of this view appears convincing, a little digging begins to unveil the cracks:

- Beyond our conscious experience, we recognise that most of what our minds accomplish is unconscious and not a matter of willpower or choice. The fact that I perceive my visual field, hear voices, and decode meaning from words—this is achieved unconsciously and we can’t will our minds to work otherwise. One might take the position that behaviours have a greater element of choice, which I’ll discuss later in this article, but we can still accept that unconscious thoughts and intentions, often emerging from background causes of which we’re either unaware or exert no conscious control over, influence our behaviour. We’re not as free as we’d like to think when it comes to decision-making.

- We should also recognise that many of our personal interests and passions are influenced by culture and experience to some extent—our favourite foods, video games, colours, sports team. Did we necessarily choose these, or were they partly influenced by our experience in an environment we just so happen to be part of? Whatever your answer, the same applies to food. For example, research suggests that many of our eating behaviours are influenced and predicted from birth due to how we were parented and exposed to food. Thus, supposing that one was habitually ingrained at a young age to see food as a response to high emotion, positive or negative, they’re probably more likely to sustain this habit into adulthood. Is that a choice they’ve made? No.

- Even if you just look deeper and more openly into your own experience with eating choices, you’ll probably realise that many actions which you assume and perceive as voluntary, such as reaching for a snack at your desk, are only voluntary in retrospect. We’d be lying to say we’re always aware of our intentions before acting. I can’t be the only one to be halfway through a biscuit before thinking, “holy shit, I’m eating a biscuit”. We might notice we behave in a certain way and acknowledge that our behaviour harmonised with our intent after the fact, but we don’t always consciously recognise our choices in advance of our actions.

So there we have three examples highlighting why our eating behaviour is less of a choice than we think it is. I realise I’ve linked little scientific evidence to this point—don’t worry, I’ll get to it—but hopefully these examples emphasise that here we’re trying to answer a philosophical question as much as a scientific one. Knowingly or not, people arguing that eating behaviours and obesity are choices are taking a position in support of libertarian free will: that we each have free will; that none of our actions are determined; that we can weigh up our options and competing desires before choosing to act in a certain way; that we make decisions based on reason; that we could have chosen otherwise. It’s to argue strongly for complete individual liberty, essentially. And while I’m not here to argue against that, the examples I’ve offered should enable anyone to recognise there are external factors that influence our choices, and that retrospectively our choices are not always as free as we think they are. But if you’re still not convinced, it’s helpful to grasp the scientific evidence contesting eating behaviour as mere choice and personal responsibility.

The Emerging Science

Despite the general view that eating behaviour and obesity are choices, emerging pools of scientific research vigorously contest this view. With a developed understanding of genetic predispositions to obesity and how our biology interacts with unsupportive food environments, there are now valid reasons to believe that eating behaviour is less of a choice than once thought. Critiquing lifestyle interventions and finding they’re not the panacea for obesity we hoped for only adds weight to this argument.

Genetic Predisposition to Obesity

Starting with genetic predispositions to obesity, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have changed how we view eating behaviour as a choice. Methodologically, GWAS studies scan numerous polymorphisms (variant forms of a specific DNA sequence) across the genome to identify loci (specific positions in a chromosome of a particular gene or allele) associated with individual traits that relate to obesity. The general notion is that if we can identify loci and patterns that associate with differences in body weight between individuals, then we can say that obesity is partly determined genetically. And indeed this is the case. Genetic differences are now said to account for ~70% of the difference in body weight between individuals, which leaves little room for personal agency and willpower to explain why one person is obese and another isn’t. That’s not to say that people are born obese—rather, genetic susceptibilities to overeating are present from birth.

GWAS have currently identified more than 250 loci associated with obesity, most of which are involved in central nervous system pathways such as the regulation of appetite. Alongside this evidence, systematic reviews of brain imaging studies report that individuals with obesity have relatively increased neural activation to the presence of food (especially energy-dense food), and more strongly activate brain regions associated with the anticipation of food reward, the emotions and memories from prior food experiences, and the visual processing of food cues such as hand-to-mouth movements and swallowing. Other reviews have also stated that individuals with obesity have weakened satiation (end of meal signals) and satiety (post-ingestive inhibition over further eating). Neuroscientists will tell you that most critical genes related to obesity act in the brain for these reasons.

So, clearly there is evidence supporting that eating behaviour is less to do with willpower and gluttony than often credited for, and more to do with the genetic roulette. Just as we have no control over our height or our favourite colour, we also have no control over the genes that influence our behaviour around food. People arguing that eating behaviour and obesity are choices will find this evidence hard to accept as it goes against their experience of authoring their own (healthful) actions, but that’s the reality. As the American philosopher Daniel Dennett has described, people “have a particular personal authority about the nature of their own conscious experience that can trump any hypothesis they find unacceptable”. Individual differences in eating behaviour are often dismissed in favour of “if I can do it, why can’t you?”.

As a side note, John Speakman offers an insightful mental experiment to help people become more self-aware of other’s conscious experiences and struggles. He says that “Tomorrow when you get up, skip your breakfast. Then skip your lunch. Then around 5pm, let’s think about how great your willpower is to overcome your appetite. It is well established that obesity is driven by elevated appetite mostly down to genetics expressed in an obesogenic environment. Your appetite at 5pm is probably what a person with obesity deals with all the time.” He continues to say that slim people “…have deluded themselves into thinking their body weight is a result of their superior willpower”.

The Obesogenic Food Environment

Moving the discussion on from genetic predispositions, though, I should clarify that although certain genes create vulnerability for eating in a certain way, they do not necessitate it. Genes are not destiny. This is because even the most extreme behavioural risk factors cannot cause a positive energy balance in a benign food environment. If there’s food scarcity, or even if the amount and type of food available is akin to foraging societies, then obesity is unlikely regardless of genetics. Thus, when determining any individual and societal risk of obesity and the degree of ‘choice’ that exists independent of genetics, the interaction between genetics and the food environment is critical. This leads to the second research pool that contests eating behaviour and obesity as choices, which uncovers how changes to our food environment have exploited genetic predispositions to overeating:

The amount of available food energy has increased substantially. Using data from nationwide surveys, Swinburn et al. found that, on average, food energy availability per capita in the United States has increased by 500 – 700kcal per day since the 1970s. Similar global analyses have been performed by Vandevijvere et al. with similar findings across countries; the increase in food energy supply was more than sufficient to explain the increase in average body weight since 1970 in 36 of the 54 countries studied. This prompts the question, then, that if the amount of food people eat is simply a choice, then why does food energy intake associate with changes in food energy availability? Well, probably because the food environment influences human behaviour. People might counter this by saying that society today just lacks willpower and eats whatever is available, but that would still be them admitting that external factors do, in fact, influence human behaviour. It’d be silly to think that obesity rates would still be high if the food environment from the 1800s still existed today. Things are different now.

- The type of food energy available has become more hyperpalatable. Systematic reviews of dietary intake in the US and the United Kingdom have reported that > 50% of total energy intake is now sourced from ultra-processed food (UPF) consumption. A substantial increase since the 1970s. And although not technically true, the rise in UPF intake suggests there’s also been an increase in the consumption of more palatable foods that promote overconsumption, since UPF’s are generally foods high in salt, sugar, fat, and artificial flavourings. So, how does the increased availability of hyperpalatable foods integrate with the idea of eating behaviour as a choice? Not very well. Randomised controlled trials of ad libitum food intake show that subjects spontaneously consume ~500 kcal more per day eating ultra-processed foods than unprocessed foods. Thus, we cannot say that “people nowadays just lack willpower” because we’ve literally tested the same people’s eating behaviour (i.e. the same degree of willpower) when exposed to different food environments. Eating behaviours change considerably.

- Marketing and advertising have shifted the perception of normal eating habits. To facilitate changes in food energy availability and food type, we also have to appreciate that marketing and advertising only promote the consumption of more food (primarily UPF). The transition in food advertising and marketing has led to the normalisation of unhealthy foods such that they’ve become societal norms, and actively following healthy eating behaviours (high intakes of fruits, vegetables, legumes, fish, etc) is now considered ‘dieting’. Whether you look at TV adverts, billboards, delivery apps, or various forms of product placement online, we see images of donuts, cookies, and milkshakes more than broccoli, blueberries, and beans. We simply cannot overlook the fact that our innate food preferences are commercially exploited for financial interests, resulting in more seductive and rewarding foods than we’re evolved to handle.

- Social deprivation constrains individual choice – Lastly, when discussing the freedom of choice in people’s eating behaviour, the undeniable socioeconomic issues that interfere with healthy habits are too often sidelined. I’m far from an economist, but basic statistics will tell you that although nominal wages (total earnings per hour) continue to increase, real wages (the relative purchasing power of a given wage) continue to fall. People’s financial freedom has reduced, meaning less money to spend on buying, storing, and cooking healthy foods. In fact, a spending and income analysis in the UK calculated that the poorest half of the population would have to spend ~30% of disposable income to meet the Eatwell Guide’s targets (and up to 73.6% in households in the lowest 10% of income). So while the supply of unhealthy foods might indeed be meeting demand—the density of fast food chains is linearly associated with increasing social deprivation—the demand is not necessarily a product of free choice. Rather, the demand is often a product of constrained choice driven by socioeconomic issues. At some point, feeding your entire family for the day with £15 worth of Mcdonald’s becomes the sensible option. There is no requirement for electricity and gas, you get a sufficient amount of calories for a low cost, and there’s minimal time and travel involved. Large parts of society have essentially been pigeonholed into buying unhealthy foods that might appear to be “bad choices” by more privileged folk, but are actually good choices when all factors are considered.

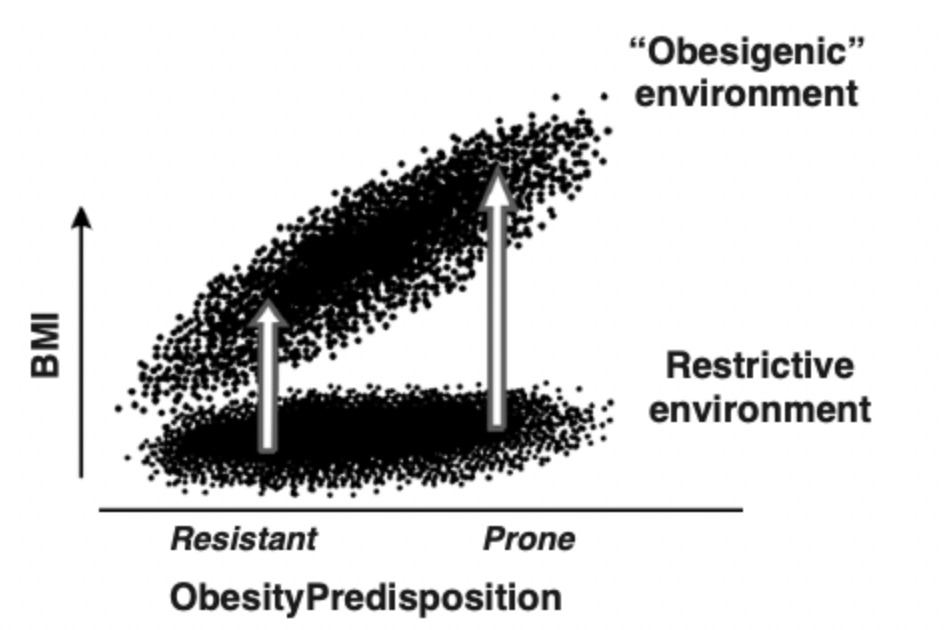

Overall, then, although our genes haven’t changed much since obesity rates accelerated in the 1970s, our environment has. I therefore paraphrase the saying that “Genetics loads the gun, and the environment pulls the trigger”. While individual variability in body weight exists in all food environments, the potential for weight gain is obscured in a restrictive environment and expressed in an obesogenic environment. In opposition to the notion that “eating behaviour and obesity are choices”, we now see a developing argument that the risk of obesity is just as much down to chance (genetic privilege and exposed environment) than choice.

Poor Results from Lifestyle Intervention

The evidence from lifestyle interventions presents the final research pool contesting the idea that eating behaviour and obesity are choices. The reason why is simple—although diet and exercise interventions (‘willpower-based’ interventions) can indeed prevent weight gain and promote weight loss, the long-term data supporting their efficacy does not meet expectations and is often underwhelming. If we go by usual standards of what defines clinically effective weight loss, it’s a 5% loss in body weight or more. But since lifestyle interventions only lead to ~ 5% body weight reductions (on average) in the best-case scenarios, they’re only considered borderline effective at a group-level. A meta-analysis of 29 long-term weight loss studies demonstrated that over half of all weight lost during dietary intervention is regained by two years, and 80% by five years. Similarly, due to energy compensation mechanisms (increases in energy intake and/or reductions in general activity), weight loss from exercise is typically less than predicted from additive energy expenditure models. Sure, some people will experience life-changing weight loss from lifestyle changes alone, but these cases shouldn’t invoke generalised statements. Not to mention that people who’ve experience dramatic changes from lifestyle interventions can still be explained by biological variation (i.e. they’re genetically inclined to sustain these behaviours), not to be used in the context of population averages.

Also, studies on medical treatments targeting biological regulators of body weight provide evidence that most causal paths to food choice run through subcortical (unconscious) biological systems. For example, a recent study showed that in comparison to lifestyle changes alone, semaglutide treatment (that unconsciously lowers appetite) alongside lifestyle changes led to a massive 12.4% greater absolute reduction in body weight after 68 weeks. While only 31.5% of participants lost 5% or more body weight with lifestyle intervention alone, 86.4% of participants in the semaglutide group (semaglutide + lifestyle) experienced 5% or more weight reductions. Results such as these indicate that the interaction between our biology and the environment is a much stronger determinant of obesity risk than willpower.

“Eating Behaviour and Obesity Aren’t Choices”

Based on the different lines of scientific enquiry discussed, you probably won’t be surprised to hear that the emerging scientific consensus is that eating behaviour and obesity aren’t actually choices. Giles Yeo, a popular Geneticist and Professor at the University of Cambridge, says that “obesity is not a choice…”; Michael Albert, an obesity doctor, says that obesity as a choice “is the biggest misconception we tell ourselves and our patients” and that “The amount of fat someone holds is regulated by biology, not willpower.”; an expert update of the energy balance model of obesity also clarified that the brain regulates body weight mainly outside of our conscious awareness. Unsurprisingly, then, what reached mainstream news back in June 2013 was that the American Medical Association House of Delegates voted to recognise obesity as a disease state, enabling its removal from the moral domain. Likewise, many experts started to reverse the causal obesity chain. Chronic overeating causing obesity became inappropriate—the more appropriate context was that obesity, as a disease, causes chronic overeating. In this way, obesity becomes a calculation of biology x genetics, not just a simple characterisation of a body mass index equal to or above 30.

When Science Meets Philosophy

But please don’t think of me as a promoter of this narrative. While I believe that advocates of this position raise some extremely important and valid points, backed by science, as I’ve covered in this article, I don’t strictly agree with their position of not a choice. The reason why is because I think the same arguments used to support that eating behaviour and obesity aren’t choices are identical arguments used in philosophy to argue that nothing is a choice. It’s a philosophical position to argue for the absence of free will in humans, essentially, which is not a position that I’d be confident in defending or being logically consistent with. If we accept that eating behaviour isn’t a choice, then we’d probably have to accept that smoking and exercising aren’t choices either. In fact, hard determinists argue that committing murder isn’t technically a choice. The concept of free will—defined as the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action—has been debated for centuries.

Unfortunately, however, obesity scientists currently want to perpetuate the narrative that eating behaviour and obesity aren’t choices while refusing to comment on how their position intertwines with free will. In a recent paper about whether it’s time to rethink agency in obesity, the authors mention that “It is important to state that a discussion of whether free will exists or not is beyond the scope of this article”. But it’s not. The paper is everything to do with whether free will exists or not. You simply cannot engage in a discussion about choices and personal agency concerning food without defining what choices and personal agency are, and whether they truly exist. So regardless of whether they’re right or wrong, I find it fascinating how often people take a hard stance on obesity not being a choice without knowing they’re justifying anything not being a choice. Think about it: claiming we’re mere passengers and observers of our neurobiology and how it interacts with the environment applies to every choice we make, or that we think we make. Philosophers such as Sam Harris have written books on this topic, and any hard determinist will posit the following argument that free will doesn’t exist:

- Thoughts and intentions emerge from background causes that we are either unaware of or exert no conscious control over. Thoughts that author our actions will always arise unauthored. The intention to do one thing and not another does not originate in consciousness—rather, it appears in consciousness, as does any other thought or impulse that might oppose it. People might feel as if they could have acted differently, but the alternate impulses required to make different choices would still be a result of unconscious causes. We are therefore not “free” as conscious agents, as everything that we consciously intend is caused by events in our brain that we do not intend and of which we are entirely unaware.

As I hope you can now see, then, the debate around eating behaviours and obesity requires people to be upfront about their philosophical position: determinism (internal regulation) vs free will (external regulation). If you want to argue the former, be willing to be logically consistent with your position that nothing is strictly a choice; if you want to argue the latter, be ready to combat a large body of evidence about biological and environmental influencers of behaviour. Although know, too, that the truth might sit somewhere in the middle. My own belief is that eating behaviours and obesity likely involve some element of choice despite being strongly influenced by our biology and environment, and there still likely exist controllable factors in people’s lives that can be prioritised to promote healthier behaviours. Focusing on behaviour change is not a lost cause.

The Dual-Intervention Point Model

Perhaps more importantly from a practical standpoint, too, is that even if free will were to be demonstrably falsified, and personal agency was thought to be nothing more than an illusion, most hard determinists would still argue that we should still operate as if they exist. That might sound contradictory, but remember we’re not just discussing theories here; we’re trying to identify the best way to solve the obesity epidemic. And accepting that free will doesn’t exist is probably not very helpful—it would lead to fatalism and most people would feel that lifestyle change is a meaningless endeavour. Therefore, in the face of uncertainty, do what’s probably most helpful. That’s to view obesity through a lens of genetics and the obesogenic environment strongly influencing individual choice, while accepting that each person has some control over their personal circumstances.

For this reason, I think the dual-intervention point model of obesity best outlines how obesity should be viewed going forward. Put forth by John Speakman, the model states that although biology determines an individual’s limits of fatness and leanness, ones settling point between those limits is modifiable. People don’t have a biological body weight set point—rather, genetics determines at which point regulatory mechanisms favouring weight loss or gain become more active. If body weight drops below lower bounds, the individual unconsciously becomes very hungry (increasing food intake). If body weight exceeds upper bounds, the individual unconsciously becomes less hungry (reducing food intake). Between these boundaries, however, there’s little to no internal regulation. John states that environmental pressures mainly determine ones ‘settling point’ between these bounds.

This model extends on the Drifty Gene hypothesis proposed by the same researcher. John proposed that, historically, adaptations in human genes kept us within an optimal range for survival: not too low to increase mortality risk when seriously ill or when food availability drops, and not too high to reduce chances of survival from predation. Yet due to the removal of predation as an evolutionary force around 1.8 million years ago, selective pressures that once maintained the upper bounds of this range dissolved. Consequently, the upper bound has trended upwards over time, and we’re now more able to reach levels of body fatness that were once unheard of. Many people (other than those genetically lucky) now keep gaining weight without any strong internal pushback.

Important to emphasise for this article, though, is that the dual-intervention model allows room for willpower and personal agency to modify body weight within the genetically-determined boundaries. For example, the model doesn’t refute that we can’t empower people to change their mindset towards life, or overcome barriers to change, and it doesn’t disregard that people can ‘choose’ to adapt their environment to favour certain decisions and start practising new habits. If I know I’m unlikely to will my way out of eating a cookie this afternoon if it’s sitting in the cupboard, then I can choose to not buy and expose myself to the cookie to begin with. As neuroscientist Daniel Kahneman would say, it’s reasonable to think that we can use our system 2 brain (rational and conscious) to promote better future decisions by our system 1 brain (nonconscious and intuitive). Planning ahead, providing yourself with some dietary structure, writing down common triggers and barriers, and how you might respond to them in the moment— these are all things that people can focus on, rather than just trying to will their way out of unhealthy behaviours. We also know from research that simply aligning our motivations with our values and preferences can support long-term body weight management, especially when supported professionally. Ongoing interaction with healthcare professionals and support groups also significantly improves weight maintenance. These are ultimately choices related to eating behaviour and obesity that any one person can make. That’s not to say there aren’t larger problems that must be addressed at higher levels—like state intervention in the market (food industry regulation) and introducing new policies (food marketing and tax) to enhance personal agency—but that ruling out personal agency and claiming eating behaviour and obesity are strictly not choices is probably more harmful than helpful.

Final Thoughts

Understanding the causes of obesity and how much we can blame individuals for their actions is vital to know how we might tackle the obesity epidemic. Some people will argue that eating behaviour and obesity are merely choices. In contrast, others will say they’re not choices and that it’s a combination of genetics and the environment determining our behaviours. I believe the truth sits somewhere in the middle. We each have elements of control in our lives, but we often underestimate the influence of internal and external factors outside of our control. Tackling obesity, therefore, is something that can be helped but not solved by sufferers of the problem. People with obesity can make habitual changes to better their situation, and perhaps this will be enough for some people to eradicate their health problems, but the major change needs to come from higher powers. Eating behaviour and obesity are more products of societal issues. The food environment needs to start favouring helpful behaviours (changing food availability and type), food companies need to be regulated so that food stores aren’t flooded with calorie-dense junk, and socioeconomic issues need to be tackled so that people have the time and money to make better choices. Personal responsibility exists, but it’s not the major driver of obesity.

If you’ve enjoyed this article and want to support My Nutrition Science, please consider donating to us. Your contributions keep the website running and the content flowing. Please also subscribe to our email list below for future updates.