Background

As per the Merriam-Webster definition, ‘reductionism’ is the procedure of reducing complex data and phenomena to simple terms that are easier to understand and investigate. It’s these simple terms that allow reductionism to be useful across scientific disciplines. We only need to look at the history of nutrition science to uncover seminal insights that are rightly labelled as products of reductionism. Whether we point toward the discovery of vitamin C as the nutrient that prevents scurvy, vitamin B12 as the primary deficiency concern on plant-based diets, or protein as a vital nutrient to reduce the risk of sarcopenia. All of these are reductionist findings that have prolonged thousands and possibly even millions of lives. In fact, just the identification of these essential nutrients is thanks to scientific methods born out of motivations to understand independent food constituents, and how they may relate to various health outcomes. Health outcomes is now a rather broad term but, historically, health outcomes related to diseases of deficiency. The fundamental need to isolate nutrients to know precisely how to avoid and overcome diseases of deficiency was, and still is, pivotal. We all still make sure to get our weekly dose of orange or another vitamin C rich food (carnivores aside), vegans rightly still supplement with their notorious vitamin B12 pills, and older generations are now beginning to understand the importance of dietary protein to extend their healthy living years. Even the more holistic guidance today still emphasises the need to implement a ‘nutrient-dense’ diet—one that is dense in essential nutrients to better avoid nutritional deficiencies and subsequent health problems.

What may be surprising to hear, then, is that reductionism has recently received much scrutiny among experts in the nutritional field. In fact, reductionism within nutrition has now been labelled as ‘nutritionism’ –a paradigm that brings with it a negative connotation. Experts argue that focusing on nutrients to interpret the healthfulness of foods and diets (a bottom-up approach) leads to confusion and poor decision-making, both at the level of the public and also health organisations. So, this begs the question – why is reductionism now viewed in this negative light when it’s clearly been useful for nutrition science in the past? It’s a good question with a relatively simple answer. That is, due to the considerable and fairly recent changes in the magnitude and types of food available in the modern world, public health concerns have promptly shifted away from diseases of nutrient deficiency and toward diseases of abundance. In other words, there’s been a shift from curative nutrition to preventative nutrition. And this is a subtle yet defining shift in the focus of nutrition science. Whereas diseases of deficiency were explainable at the level of the nutrient, diseases of abundance rarely are.

Rightly so, I say. That is not to say an abundance of nutrients (a reductionist perspective) is still not part of today’s health problems—we all know of issues relating to excessive sodium, saturated fat, and sugar intake—rather, that reductionism is no longer sufficient to study and discuss nutrition. Preventative approaches to modern diseases, often with multifactorial causes by nature of their vast complexity, require a far broader understanding of food effects, dietary patterns, behavioural psychology, socioeconomic factors, and their subsequent interactions. Isolating and understanding nutrient actions is no longer enough. In turn, the lens by which nutrition has traditionally been viewed, and the paradigm by which nutrition research was conducted, has been forced to shift away from single food components.

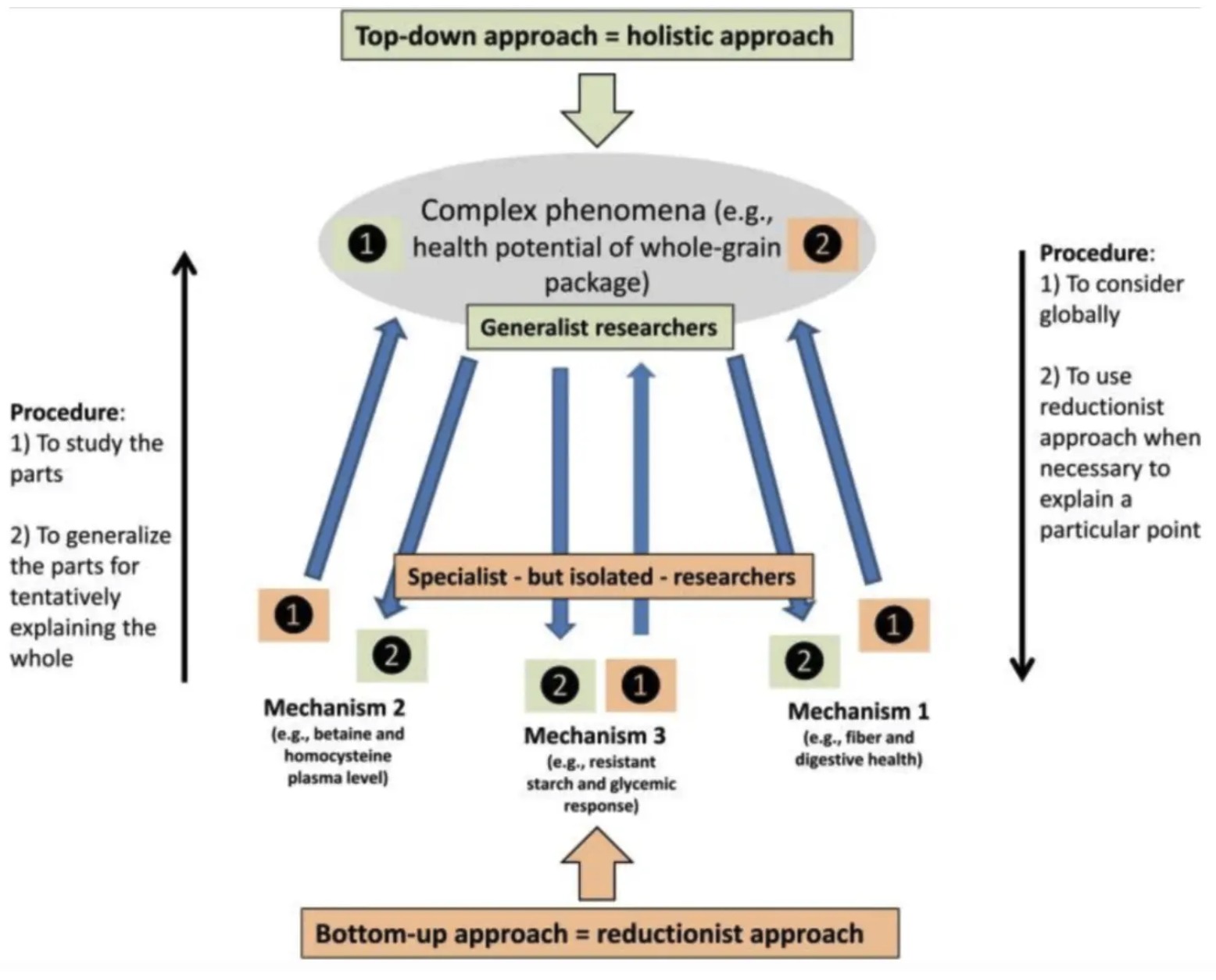

Therefore, in this article, I want to discuss my thoughts in more detail. I will outline the clear benefits of shifting the nutritional paradigm closer towards holism, while also clarifying why we should not lose sight of the benefits that reductionism still brings to the table. Ultimately, I believe a merging of these paradigms is the best path forward. Dr Anthony Fardet, a great researcher who has published many papers on this topic, states that “we must combine both of these approaches in a balanced way.. [but] we must always go from holism to reductionism, from the global to the specific”.

Reductionism

Let’s actually start with the benefits of reductionism outside of simply identifying and correcting nutritional deficiencies. I think some of these points can be overlooked. So, for me, the benefits of reductionist lines of research are to improve our understanding of more holistic lines of research. Although it may not appear obvious, understanding the relationship of nutrients with chronic diseases (or mediators of) enables a deeper understanding of research that analyses foods, dietary patterns, and health outcomes. Reductionism provides insight as to why the effects of food and dietary patterns may be as they are, and it also allows researchers to interpret studies of food and diet in greater detail. This ultimately reduces the risk of reaching faulty conclusions and allows for valid hypotheses to be posited for future research. Let me provide some examples…

First is an example related to better interpreting food studies based on our article on eggs and cardiovascular disease (CVD; by Matt Madore). In that article, Matt had prior knowledge that a primary way eggs would influence CVD risk was as a function of changing total cholesterol levels. This was valid assumption based on reductionist lines of research clarifying the relationship between saturated fat, dietary cholesterol, and total cholesterol (a CVD risk factor). With this background knowledge in mind, then, Matt was able to find that, even though many studies reported no significant associations between egg intake and CVD, an overwhelming number of these studies inappropriately adjusted for changes in total cholesterol during the analysis phase. In other words, the researchers adjusted (removed the effect) for ways in which the food exposure (eggs) would have influenced the outcome (CVD). This is not justified. And the relevance of this, to my point, is that background knowledge of nutrient-specific research enabled Matt to better interpret the egg research and avoid reaching a faulty conclusion. Different interpretations lead to different conclusions. If Matt took the study results literally, he probably would have said that eggs have little to no influence on CVD risk. Yet, reductionist background knowledge opened the possibility that eggs may actually increase CVD risk at certain levels of intake provided that changes in total cholesterol aren’t adjusted for. This is just one example of many, but I hope the general point is clear.

Now let’s take an example related to how reductionism aids hypothesis development in diet research. I’ll use another one of our articles on ketogenic diets and low-density lipoprotein concentrations (LDL-C; another CVD risk factor) for this. Here again, if we were to leave our level of interest to the dietary exposure alone (a ketogenic diet), we would have bluntly concluded that ketogenic diets are inferior to non-ketogenic diets for lowering LDL-C. The current pool of evidence clearly infers that ketogenic diets increase LDL-C. But while future evidence may continue to support this position (assumptions aside), we can explore the truthfulness of this inference by interrogating the nutrient exposures in more depth. Based on such data, we can hypothesise whether there is something inherently bad about a ketogenic diet, or whether it’s a matter of how ketosis is achieved that’s an issue, such as an over-reliance on animal products, saturated fat, and dietary cholesterol intake? The truth is that we cannot begin to answer these questions without putting on our reductionist hats and applying background knowledge. That’s why in my article, I looked into the primary studies and showed that ketogenic diets were almost always being achieved with animal-predominant diets that were high in saturated fat and dietary cholesterol. This information alone changed how I interpreted the research. As the ketogenic diets were being applied by increasing the intake of nutrients linked to increases in LDL-C, I speculated about the possibility of different outcomes had ketosis been achieved with other foods (in a pseudo-reality). Therefore, we can see again how understanding nutrients helps us to delve into more holistic studies, ask causal questions, avoid faulty conclusions, and progress scientific understanding.

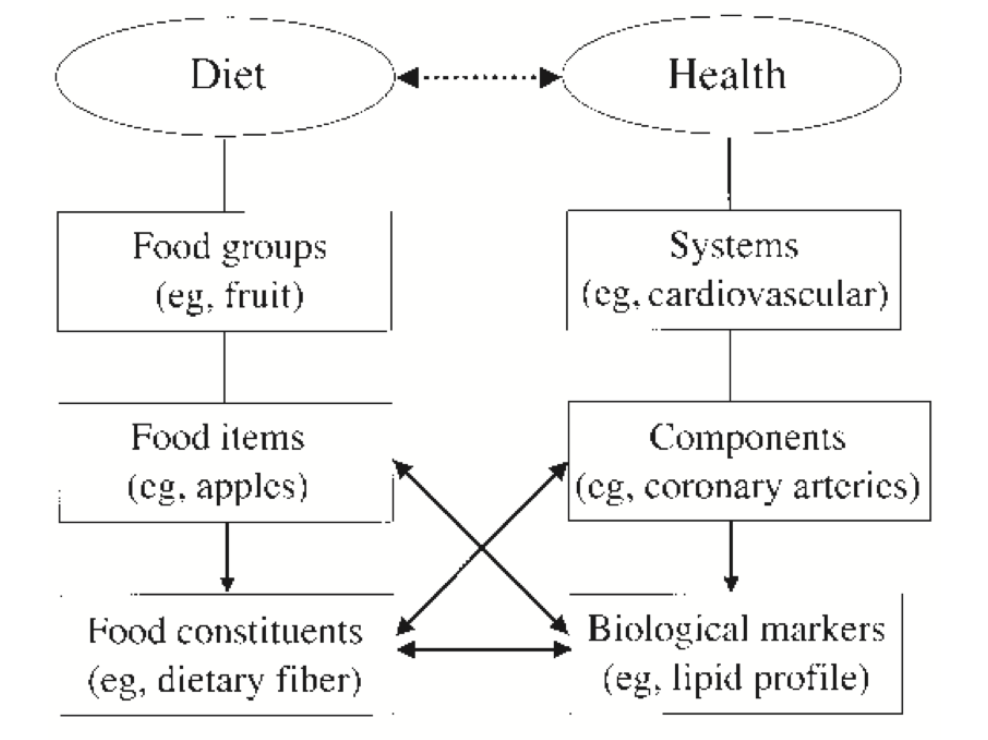

Let’s apply this practically. If we were to place nutritional exposures into a hierarchy of importance for understanding nutrition, then food and dietary pattern research indeed sit firmly at the top without competition. They are more relevant to what we do in the real world: we follow diets and eat food, not nutrients. However, this doesn’t rule out the benefits of other research areas. As Dr Anthony Fardet continually mentions in his papers, we just need to ensure we go from holism to reductionism, not the reverse. If we do the reverse, we risk piecing together numerous pieces of evidence to speculate a grand idea of the whole that is highly unlikely to be true. It’s like finding tiny segments of a hundred different maps and hoping that by piecing them together you will find a treasure chest. No, dude – just go straight to Jack Sparrow and ask him for the complete map. Or if you excuse my bad analogy and we try this in more educated terms, we could say that trying to piece together reductionist evidence violates the principle of ‘Occam’s razor’. This philosophical tool states that our starting point when interpreting a research question is to find the simplest explanation requiring the least assumptions and leaps of faith. While we can use reductionist research to our advantage, we have to know what those advantages are (as per my examples). And by knowing what those advantages are, we can build a more holistic framework that puts dietary exposures into somewhat of a hierarchy, with each layer having its own unique purpose. Published frameworks like this have officially been put forth by Ingrid Hoffmann [1] and Daniel Jacobs [2] in the nutritional literature. These hierarchies start with prioritising larger factors, such as studying foods and dietary patterns, and work down to smaller units—individual nutrients or food components—that are complementary to the larger units.

Nutrient > Food > Food Group > Dietary pattern > Health Outcome.

It also turns out that by following this hierarchical approach, reductionism can be equally useful for distributing health information to the public. I’ve learnt this myself during my time as a nutrition consultant and speaking with people about nutrition’s link with health. It really just depends on the audience. If dealing with groups that have very little understanding of nutrition, the top layer that addresses only dietary patterns is the only layer you need. I will typically spend a good amount of time explaining the difference between dietary patterns rich in ultra-processed versus minimally-processed food, or those which prioritise healthy plants foods versus those that prioritise unhealthy animal foods (no, I’m not saying that all animal foods are unhealthy). Then, if needed, I will go down a layer and use some examples of food groups to facilitate understanding, e.g. fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds fresh meat and fish. Then, if needed I will go down another layer and explain the differences between the types of foods within these categories, e.g. types of dairy, types of meat, types of legumes, and types of fruit. Then—and only then—may I opt to use layers of reductionism to categorise foods or dietary patterns as those ‘higher in fibre’ or ‘lower in sodium’ to help explain why these foods and dietary patterns are beneficial and for what specific goal(s). I might connect ‘higher protein foods’ to gaining muscle (meat, dairy, legumes etc) and ‘higher unsaturated fat foods’ to reducing CVD risk (avocado, nuts, seeds, vegetable oils etc), but only if the audience is appropriate and ready to hear such information. Granted this level of reductionism is usually not required, but we can still see that discussing nutrients can help people to make connections between foods, diets, and why they may or may not be helpful.

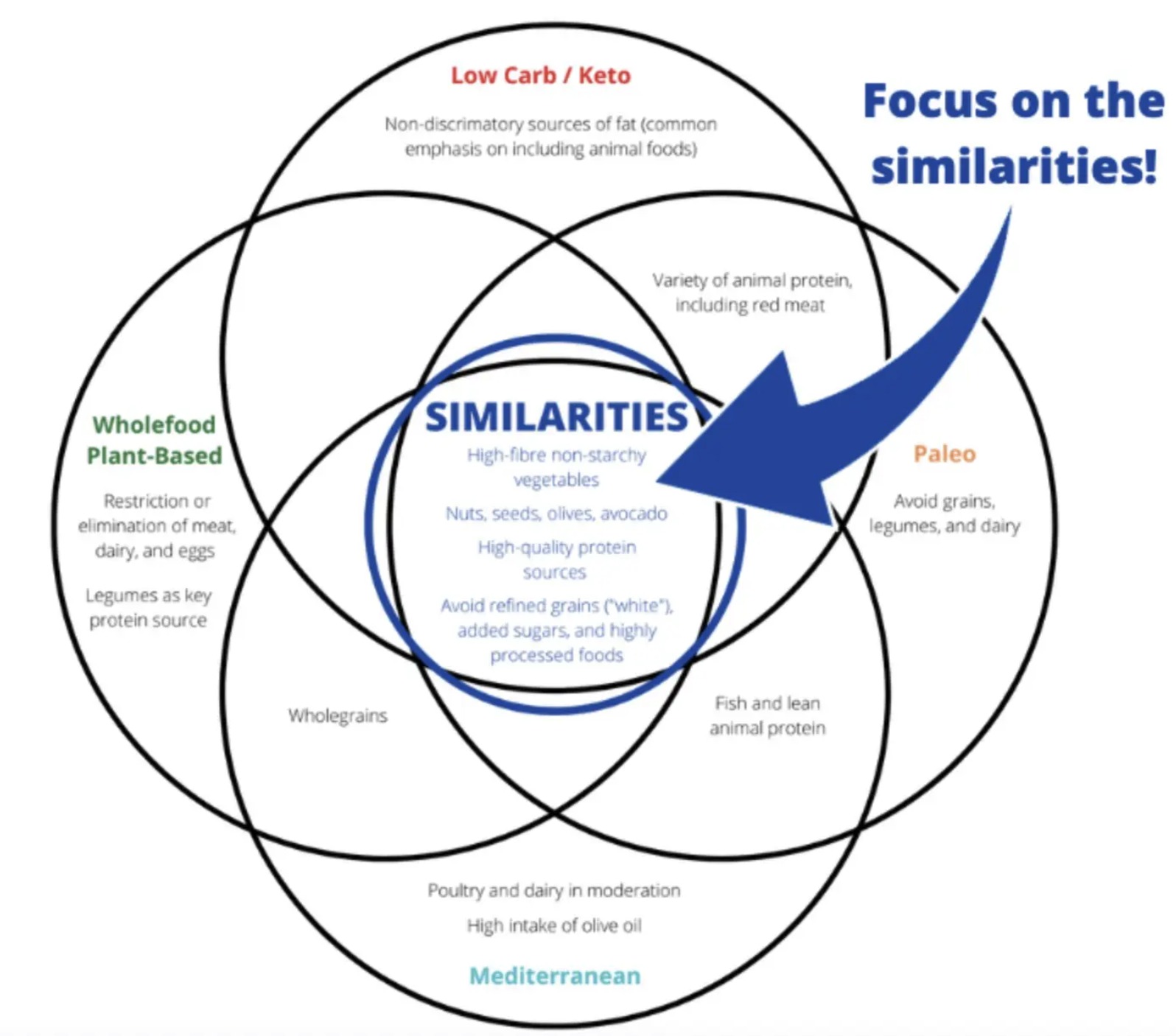

The harsh truth is that failing to appreciate what matters—food and dietary patterns—inevitably leads to paradoxical food choices and public confusion. Think for a moment about mainstream nutrition advice: “eat less saturated fat, salt, and sugar” but also “eat more fiber, antioxidants, vitamins, minerals”. Even if we’re to argue that this is technically sound advice, how is a layman meant to practically comprehend these recommendations? First, they would need to know what foods contain these nutrients (so they need to be educated on food regardless). Second, they would need to subjectively decide what constitutes a food being “high” enough or “low” enough in these nutrients to warrant consumption. And even then, paradoxical dietary choices are guaranteed. For example, fresh meat is high in saturated fat but high in vitamins, minerals, and protein – good or bad? Fruit contains a lot of sugar but is high in fibre and antioxidants – good or bad? It’s silly. Therefore, we really need to focus on a food-first approach to public health. Visual tools such as the Venn Diagram below can be incredibly useful for this reason.

Holism

Now that we have covered the benefits of reductionism, let’s move on to the issues we must consider. Let’s also justify why we must always go from holism to reductionism and not the reverse. So, the best place to start is to re-emphasise a point I mentioned earlier – that the risk of focusing too heavily on reductionism is that you end up trying to piece together isolated nutrient actions to form a largely speculative view of nutrition and health as a whole. This approach aligns strongly with how conspiratorial belief systems are formed. That is, formulating an idea based on a single piece of evidence and then extrapolating from it unjustly (with vast assumptions and leaps of faith) while rejecting stronger alternate positions with fewer assumptions. Stated bluntly, we should not run before we can walk. Likewise, we should not add more assumptions and logical leaps of faith to defend preconceived notions of what “makes sense” in the face of contradicting evidence. A clear example of this is the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity. This hypothesis posited that carbohydrates (reductionism; a single nutrient) are a primary driver of obesity, despite a myriad of experimental and non-experimental evidence on foods and dietary patterns (holism) high in carbohydrates suggesting otherwise. No matter how hard someone might try to use reductionism to prove carbohydrates are a primary concern (which is still largely absent anyway), we can simply use more holistic research to falsify the hypothesis.

Still today, though, too many people attempt to justify an overly reductionist “bottom-up” strategy where complex ideas about nutrition and health are formed almost exclusively from our understanding of nutrients. This is problematic for reasons I’ve already outlined, but also because it leads to the never-ending cries of “we need more evidence”—presumably another way of saying that “I can justify any position I want until I know of every possible nutrient action and interaction in existence”. Perspectives like this are surprisingly common in the field of nutrition even when clearly futile. If we look to the extremes, ideological movements such as the carnivore diet largely stem from the complete and utter disregard of almost all the nutrition literature studying food and dietary patterns. Observational literature–fundamental to understanding the latter’s relation to human health–is thrown out of the window without deep thought. It’s assumed to provide no real answers, nothing of any explanatory value, only telling us what happens but not why. We should push back against this extremist and frankly dangerous way of thinking as it ultimately stems from ignorance; only a more holistic paradigm and a “top-down” approach encompasses the evidence base that we already have to form logical conclusions. While science aims to leave no questions unturned, and studying the impact of diet down to individual elements is still of interest, we must be unrelenting and brutal in attempts to map out detailed causes of inherently complex metabolism and pathology.

Unlike the biomedical that relies on RCTs to nail down the effects of single compounds, the benefits do not apply as strongly to nutrition. Don’t get me wrong, RCTs are amazing for their intended purpose, but they simply cannot bear the weight of a holistic nutrition model. No single study design captures dietary effects in their entirety [7] [8] [9]. RCT’s rarely look at a contrasting array of nutrient intakes (from very low to very high); RCT’s seldom have a true placebo or zero exposure comparison group; RCT’s may inadvertently study the wrong population or the wrong type of exposure at the wrong time in the disease process; RCT’s tend to have lower external validity than non-interventional designs that observe real-life behaviours; RCT’s are less inclined to measure long-term health outcomes insofar as they’re limited by study length and ethical considerations. Also, RCT’s focusing on single nutrients prompt failure to consider the effects of dietary substitution, meaning health outcomes are thought of as consequences to absolute changes in a single exposure rather than relative changes to a comparative exposure. You see the problem. With this in mind, unjustifiably supporting a reductionist approach to nutrition science fails to recognise that RCTs and observational studies are answering different yet equally important questions. If we aim to fully appreciate the relationships that food and dietary patterns have with various health outcomes, we must consider more holistic lines of research (non-interventional, observational designs). These designs are nothing short of integral to a “top-down” approach in nutrition science. Studying dietary effects across multiple research designs reduces the chance of missing important effects while also identifying non-causal associations. In turn, we broaden our knowledge of dietary patterns, foods, and nutrients, while enhancing the quality of evidence that we use to divulge nutritional recommendations [10]. Again, the priority is the study of foods and food patterns (with interventional and non-interventional approaches), while information on individual nutrients or food components is complementary.

Final Thoughts

Reductionism and holism have unique benefits and we should merge these paradigms to progress nutrition science. Holism allows us to focus our attention on what matters most, while reductionism is crucial for addressing nutrient deficiencies and aiding our interpretation of more holistic research. A lot of interesting nutrition hypotheses also stem from reductionism. So let’s not fight; instead, let’s merge these paradigms together and collectively improve our interpretations and discussions of nutrition science.

If you have enjoyed this article and would be kind enough to support our website, then please consider donating via this link and signing up to our email list below.