Background

There is a lot of misinformation about everything, but nutrition sets itself apart with its sheer volume of verbal garbage. Nutrition misinformation is literally everywhere: over the dinner table, on TV adverts, at supermarkets, in the workplace, at the gym, on social media, in doctors’ surgeries, and so on. You could say that it’s the responsibility of nutritionists to clarify the information from the misinformation, yet this motivation is hard to sustain when discovering that everyone else is a nutritionist, too. Not a certified or experienced one, of course, but a nutritionist to the same degree as you are nonetheless. I don’t think that many other professions have the same problem; the division of labour is a systemic part of all working societies to relieve people from needing sufficient knowledge or capabilities in all areas. Nutrition, however, is a special little pony, where domain-specific expertise disintegrates into thin air. I don’t know why – my best guess is that because everyone eats, everyone has an instinctive urge to claim expertise about what they eat, when they eat, how much they eat, and why on earth anyone else would choose to eat differently. Humans are uniquely connected to food in a physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual way (if that’s your thing) that differs from other areas of science. Food is and always will be a central part of human life. Honestly, I once consulted a woman who hadn’t eaten bread in 10 years because her gardener told her it “instantaneously turned to fat”. The fucking gardener.

Anyway, that’s why I’m writing this article: to spread awareness of nutrition misinformation, understand what sparked the misinformation wildfire, and highlight how to identify the perpetrators of claims that do not align with scientific evidence. I feel obliged to comment on the state of nutrition before (I predict) my consultations continue to fade into a waft of nonsensical debate instead of healthy discussion and instruction. Let’s begin…

The Nutrition Misinformation Wildfire

Nutrition misinformation has always existed. Eating testicles for muscle gain, herbs to achieve spiritual enlightenment, and rotten eggs for strong bones. You name it, it’s probably been a ‘thing’ at some point. What is apparent, however, is that nutrition misinformation was always restrained by time and location. Each strange habit was exclusive to a particular population and didn’t necessarily catch on to proceeding generations, allowing most pieces of nutrition misinformation to naturally die without intervention.

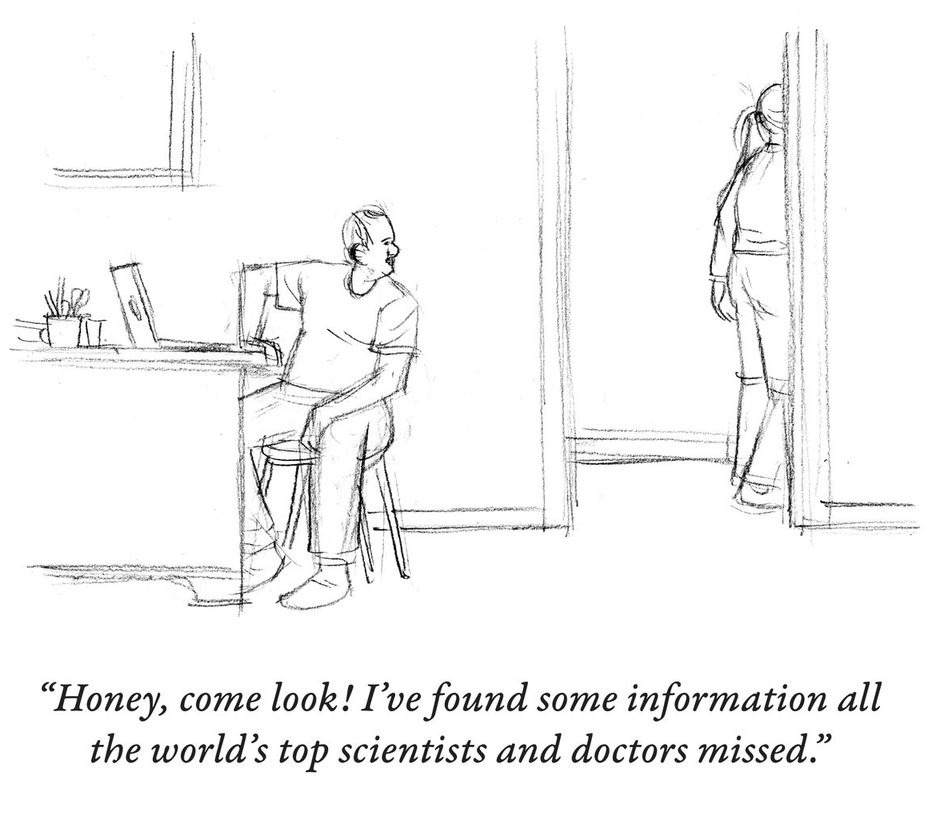

Then came about the internet, granting near-universal access to almost everything known by a combination of targeted (search engines) and passive (social media) exposure to information. No longer did we have to seek the intelligent mind in our close-knit group of friends or head to the library to ponder over the unanswerable question—get out your phone or computer and pursue the answer in a matter of seconds. The internet also meant that scientists no longer had to drain their souls in a library, and even the layman was provided with the tools to become their own secret researcher. With access to thousands of websites, books, social media pages, and syncing up with the minds of world-leading experts to exchange ideas and collate thoughts, what could possibly go wrong?

Turns out a lot. While it may sound like merging human curiosity (an evolutionary positive trait) with an infinite portal of information unlocks the door to progress, this has not been the reality for nutrition. With the ability to create information from thin air (i.e. not based on data) and the freedom to share opinions regardless of truth, the internet has unchained misinformation from the factors that once kept it restrained: time and location. While people can certainly find nutrition truths on the internet if they understand where and what they are looking at, this prerequisite for accumulating knowledge is unfortunately met by few. The vast majority of interested folk are simply unable to separate fact from fiction, and considering the internet has essentially zero filters on the quality of information it contains, we now find ourselves in a world of so much confusion that even the basics of nutrition—”eat your fruits and vegetables”—is publicly questioned.

In an ideal world, we might hope that people prioritise information that is distributed by nutrition experts (as determined by valid certifications and professional bodies), but this is not the world we live in. The world we live in is one where people either don’t bother to understand nutrition at all, or they are forced into synthesising what they perceive as the closest representation of the truth within a tidal wave of conflicting opinions. The latter option is a neverending shitstorm, though. As I’ve described, the lack of barriers online provides the perfect platform for thousands of self-proclaimed “experts” to misinterpret and mislead people down dangerous paths. In fact, we call these self-proclaimed “experts” by the name ‘Quacks’: a person who pretends, professionally or publicly, to have skill, knowledge, or qualifications they do not possess. Nutrition is rife with them given the internet allows for equality of reach yet an inequality of expertise. Don’t believe me? Join Twitter and you will find endless nutrition accounts run by individuals with a lack of (or zero) formal training, no reputable credentials, and no need to adhere to a professional code of conduct. Unfortunately, social media has no filtering or fact-checking when it comes to nutrition, just deafening and repetitive voices that enable misinformation to thrive at the touch of a button.

So, what do I suggest we do to combat nutrition misinformation? Well, a few things, but most of them are relevant to policy and education instead of individual-level change. Regarding the latter, though, I recommend either of the following options:

- put more trust in information from nutrition experts and authorities, and/or

- learn to think critically and accept personal and social responsibility to distinguish between informed and misinformed content.

Either of these options is fine. Option (1) is the easier one but I won’t recommend it otherwise I’ll be criticised for “appealing to authority”. I will say, though, that if you don’t want to do (1) then you must do (2). There is no option (3) that states you do neither (1) nor (2) so you simply believe whatever you want to believe—this is how misinformation enters society. Take your pick, (1) or (2)—I know that many readers are competent at (2) already, in which case ignore my ramblings.

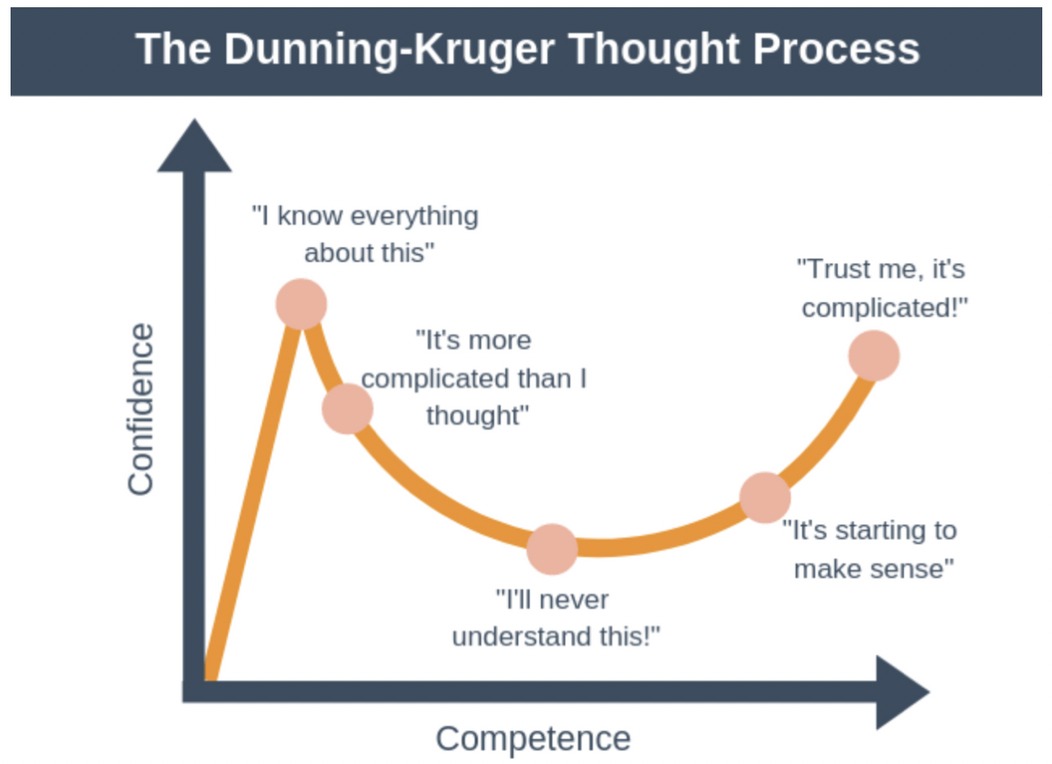

Be Aware: Dunning-Kruger

The only issue with listing the above options for avoiding nutrition misinformation is that achieving (2) is subjective. We know that being a critical thinker is to objectively analyse and evaluate evidence to form a judgement, and to rely on the scientific method to form our positions as opposed to instinct or intuition, but how do we know when we are competent enough to form our own opinions, even if they differ from experts? This is a difficult question to answer and, unfortunately, Quacks tend to be those believing they’re competent when they are indeed not. As Daniel J. Boorstin stated, “the greatest enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.”

Although Quacks may parallel true experts by using the word “evidence” to support their claims, they tend to perceive evidence as things they perceive to be true rather than things they have subjected to an apriori set of steps to navigate through bias and error. Common sense, indicated by phrases such as “that makes sense”, tend to be all that Quacks rely on for good evidence despite being a guaranteed road to misinformation. Not only this, but even when Quacks spend weeks, months, possibly even years researching nutrition science, they can still easily fall victim to the Dunning-Kruger effect.

As shown above, and in contrast to the assumption that the more knowledgeable we are, the more confident we are in our knowledge, Dunning-Kruger expresses that ignorance trumps knowledge for producing confidence. I have been no exception to this and I am sure that you haven’t either (for nutrition or otherwise). My confidence in nutrition knowledge before even starting my University course 9 years ago was sky-high. When my older brother asked me before University whether I was nervous about starting, I literally remember saying “I know it all already” with utter confidence, which is possibly one of the cringiest moments of my life so far. I knew a little bit, but I had no idea of the scope of what I didn’t know. I would say that only in the last couple of years am I now in a position to be reasonably confident in the positions I hold and defend them reasonably well if questioned. That’s a pretty long time to become competent, and even still, I know that I have infinite amounts to learn before the stress of learning itself sends me beneath the soil. Those I know beyond me regarding nutritional knowledge and experience would probably agree with this sentiment.

But let’s say we’re on this journey toward competency and we just want to know who to listen to, who to learn from about nutrition, and who to be wary of to avoid being misled, how do we do that? Well, there are a few ways, and I decided to choose the most fun way for this article: to learn everything about what not to do when learning about nutrition by understanding the traits and tendencies of nutrition Quacks themselves. Therefore, I came up with a ‘How to spot a Nutrition Quack’ theme as an indirect learning tool for developing critical thinking skills. Because let’s face it, if you can easily spot a nutrition Quack, you probably know how to avoid becoming one, which places you on track to be a reliable source of nutrition information.

How to Spot a Nutrition Quack

1. Reliance on Story-Telling and Anecdotes

The first pointer to spot a nutrition Quack is to identify when people rely on anecdotes and storytelling to justify their claims. This is not to say that storytelling isn’t a valid learning tool among professionals, but that Quacks know skillful storytelling is the most effective way to grab the attention of the ignorant. The default mode of human thought is narrative cognition and most people are far more receptive to (oversimplified) narratives, painting a picture that resonates personally. Quacks take advantage of this. You will notice their primary way of spreading information is to tell stories instead of delving into scientific data. Quacks know that when competing with other sources of information for public attention, especially when the totality of information appears cluttered and conflicting, the layman will resort to the person who provides shelter in the storm.

It is no surprise that the most popular narratives in nutrition are those demonising a single food or nutrient—they offer the simplest of narratives, i.e. eliminate carbs, fat, meat, or plants. It’s also no surprise that the people with the biggest audience in the nutrition industry perpetuate nutrient and food demonisation. Telling someone that one nutrient or food is to blame for all problems appeals to those with minimal background knowledge yet wanting to become a subject expert with little to no effort, regardless of how extreme or scientifically validated that narrative is.

The best part for Quacks is that stories are intrinsically persuasive. Whereas the science of nutrition aims to provide generalised truths from overtly complex data, narrative communication starts with a presumed truth (a personal experience) and then speculates about a generalised truth without data; all that matters to Quacks is what they perceive as the undeniable truth based their experience. It’s far easier for someone to believe a story as it requires no grand justification for its accuracy; the story itself is thought to demonstrate the claim reliably. This means that, unfortunately, it takes just one story for a Quack to believe they have falsified a large body of valid scientific evidence, while in contrast, it takes a myriad of valid scientific findings to make Quacks realise their narrative is not groundbreaking and fits within generalised truths. This remains true even when the story is accurate, which is a grand assumption given neither our memories nor our perceptions are necessarily trustworthy. Even if they were, the plural of anecdote is still not data.

We must take a stand against Quacks that insinuate anecdotes and science supply us with equal levels of the truth. Sorry to spoil storytime, but they do not.

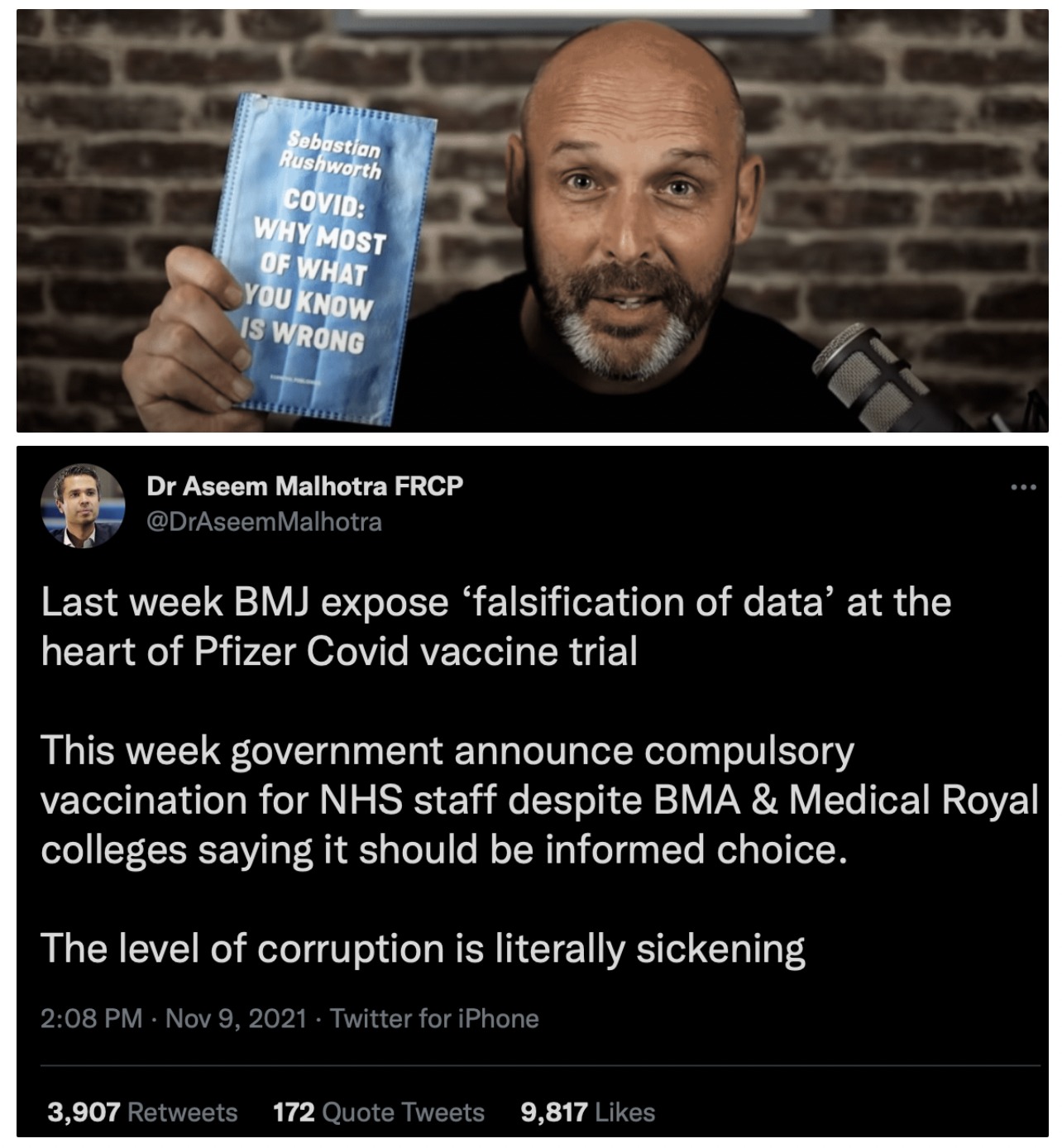

2. A Contempt for Expertise and Scientific Consensus

The second pointer to spot a nutrition Quack is they’re likely to have a contempt for scientific expertise and consensus. This contempt will not only apply to the nutrition field but actually to all scientific matters. The rejection of expertise will be a running theme. As an example, possibly one of the only positive things that has happened during the Covid pandemic is that we’ve been gifted with the perfect opportunity to see which nutrition “experts” who should be taken seriously and which should not. It didn’t take a rocket scientist to gather those pushing the most extreme dietary approaches also tended to be the ones pushing anti-vaccine, anti-lockdown, and anti-mask misinformation because of some wild government or pharmaceutical conspiracy.

I’d actually say it’s pretty rare for someone to hold an extreme view of nutrition without holding extreme views on other matters, so this is always worth being mindful of when considering your go-to sources of information. Many Quacks genuinely believe that information spouted by qualified nutritionists is inherently wrong and part of a corrupt education system. Quacks will attempt to collapse an educational network into ‘they’, or generate a cult-like war between ‘us’ versus ‘them’. Even me, I’ve genuinely lost count of the number of times I’ve been told that the education system brainwashes me, or that I don’t learn independently, or that my 2013 lecturer in Human Nutrition is going to spank me for progressing my knowledge beyond his classroom. It’s mental. Let’s be honest: if I wanted to gain financially from nutrition, I would be a Quack with a Twitter handle of @TheKetoGodShaun tomorrow and accumulate 100,000 cult followers with endless pictures of buttered steaks.

The only problem when trying to decipher whether someone is anti-authoritarian and has a contempt for expertise is that it isn’t always obvious. While some Quacks wear their rejection of expertise as a badge of cultural sophistication, others survive by claiming to be “free thinkers”, a much subtler claim. Take Dave Feldman as an example of a subtler nutrition Quack, for example, who is an engineer by trade. He often gets hand-waved as a “free-thinker” for telling himself and his thousands of followers to “do your own research” when a nutrition authority figure (such as a professional nutritionist or expert body) suggests that people do something (like making a specific dietary change) for their own good, but he is everything but a free-thinker. Dave will decide what a study shows and does not show, and what the collection of evidence infers, regardless of the appropriate scientific method and basic logical consistency (later discussed). He’ll imply that he and his audience have special knowledge to contend expert advice, which we know is likely wrong as per Dunning Kruger. In reality, his suggestion to contemplate the rejection of expert advice without good reason is a way for him to assert autonomy and protect his fragile ego that doesn’t want to be told what to do, or that he’s probably wrong. Sure, my choice of words here might be regarded as a harsh, but I see no reason why they’re untrue. Dave and others will contend my stance by claiming to be “sceptics”, not denialists (a Quackery trait), but there is a very fine line between scepticism and denialism. Denialism is a knee-jerk “I doubt that” whereas scepticism is a healthier “why do we think that?”. Scepticism highlights a persistent intrigue to know more but doesn’t necessitate the rejection of expertise or consensus; on the other hand, denialism is a stubborn and persistent refusal to accept what the evidence shows beyond a reasonable doubt.

You might wonder why Quacks take an anti-authoritarian approach but the answer is obvious – why else would anyone listen to them? The reality is that if Quacks repeat what has been said by experts for decades, there would be no urge for people to listen. For Quacks claims to be acknowledged and accepted by others, and for them to ultimately grow an audience, it’s a requirement to disregard the scientific expertise and consensus. They need to make their claims immune to scientific evidence and have their audience perceive any contradictory evidence as inherently rigged by those with personal or financial interests. That’s why when evidence opposes a Quacks beliefs, they simply blame “Big Pharma”, “Big Agriculture”, or “Big Broccoli” for twisting the data and trying to dupe those believing they are too special to be duped. It’s a somewhat successful strategy that manages to turn the top-down structure of information flow on its head, whereby unregulated propagators of misinformation replace organisations and professionals.

3. Delusion of Cognitive Bias

The third pointer to spot a nutrition Quack is to look for ignorance of cognitive and confirmation biases. These are fancy phrases:

- Cognitive bias is defined as a “systematic pattern of deviation from the norm or rationality in judgement”.

- Confirmation bias is defined as “the tendency to process information by looking for, or interpreting, information that is consistent with one’s existing beliefs”.

In combination, these biases explain why we not only defend our beliefs more so than we defend opposing ones (cognitive bias), but we actually interpret and simplify information in a way that confirms our current beliefs (confirmation bias). These biases may sound like traits that are exclusive to Quacks, but there is no doubt that we are all biased to some degree; bias is inescapable. No matter what dietary approach we currently think is most well-supported and for what reason(s), we will naturally gravitate toward pieces of evidence that solidify these beliefs. This is because to hold a strong position about anything (such as a nutrition topic) means that we must necessarily think that it’s a good one; we don’t hold strong positions that we believe are bad. Some may argue that, for this reason, no one can ever be truly objective; everyone is victim to some degree of cognitive distortion when interpreting the same pool of research.

But as I said, the problem is not with biases themselves—rather, the problem is being ignorant to them. Quacks fail to recognise their biases, interfering with their ability to think critically and reach logical conclusions. You will get this sense of “I know it all” from Quacks as if they are too special to be duped. But denial of susceptibility to bad ideas is precisely what allows us to hold them to begin with. The only way to protect ourselves from bad ideas is to acknowledge that we’re all capable of holding them, and not acknowledging this is one of the fastest ways to lower our guard to misinformation before becoming yet another distributor of it. I mentioned this in a recent tweet while suggesting that people shouldn’t follow anyone that hasn’t previously admitted to being wrong or that isn’t clearly open to being wrong in the future. Harsh yet true. You will find that most popular social media nutrition accounts are run by people who take far too much pride in being right—the admittance of being wrong presumably entails some form of cognitive discomfort.

One point to note is the paradox that presumably smart people (such as Doctors trying to cross over to the nutrition field) can also hold faulty beliefs. Scan social media and you will soon find hundreds of doctors—presumably smart people—chanting clear misinformation from the rooftops: “insulin causes obesity” and “seeds oils cause disease”. This has led people to believe these Doctors must either be purposely lying for personal gain, or are just intellectually dishonest—surely they cannot be so naive with so many letters after their name? I have a slightly different take. Firstly, the nature of social media means that we’re far more exposed to the minority of “smart” doctors holding faulty beliefs than accurately represents the widespread consensus of doctors and health professionals. Secondly, I believe that smart individuals can be more susceptible to faulty beliefs as they’re simply better at rationalising them; smart people can convince themselves of bad ideas more easily due to their intellectual ability, rhetoric ability, and argumentative ability. There are obviously some more nuanced issues too—nutrition science has unique complexities that Doctors don’t always recognise—but my general points stand.

Combine the above with the fact that some doctors clearly gain some personal attachment to their nutrition beliefs over the years (i.e., I am a “low carb doctor”) and it’s easy to see where the issues stem from. Biases are more likely to produce persistently false beliefs when they stem from issues closely tied to the conception of self. And seen as what you eat is not always about ‘what I do’ but often ‘who I am’, the problem is especially pertinent to nutrition. You see this on social media all the time: when you question someone’s nutrition beliefs, it’s as if you’ve launched a personal attack on someone’s self-worth. It’s a real problem as when there’s a battle between external facts and internal values, internal values prosper. Remember that some people have often held these nutrition beliefs tightly for decades and they’re likely mistaken to think the ideas they hold most fervently contain more truth.

But at least for now, we can recognise that although our biases can never be eliminated, they can be minimised. We’re not rendered indefensible against our natural tendencies. How so? By learning to suspend our acceptance of a particular narrative until it has been confirmed, and choosing to reflect on statements rather than intuitively accepting them. This strategy does not necessitate being a centrist—this is also biased due to the middle ground fallacy—but instead to provide ourselves with the best opportunity to reach a judgment closest to the approximate truth. Bad ideas are invariably the consequence of the lack of self-reflection.

I forgot who told me this but I’ve held onto it ever since: “self-reflection means criticising bad ideas no more than we criticise good ones”. For whatever reason this stuck with me; it made me realise that as we necessarily hold only good ideas, and most people choose to criticise only bad ideas, then by extension we often don’t criticise the ideas we hold—the exact opposite of self-reflection. Granted, there are times when a scientific position is considered “beyond reasonable scientific doubt” for sake of practicality and to prioritise knowledge progression, but generally speaking, we should always seek out those of contradictory opinion and offer a way (i.e. an epistemic standard) for our beliefs to be falsified. I now regularly subject myself to a bias minimisation test that consists of asking, “have I subjected my own beliefs to the same scrutiny that I apply to others?”. It’s still surprising how often the answer is “fuck no”.

4. Excessive Posting to Drive Confusion

The fourth pointer to spot a nutrition Quack is the excessive posting on social media. This pointer is a little more controversial as I know many well-informed nutrition enthusiasts that seem to post non-stop on social media and I don’t want to offend, but hear me out. Quacks don’t need to disregard expertise and disprove scientific consensus to build an audience and spread misinformation; instead, all that Quacks need to do is induce sufficient doubt to make people believe that controversy exists. And to do the latter successfully, persuasion of controversy by overwhelming exposure to a false narrative is more than adequate. A valid scientific explanation is not necessary.

So if we look toward social media, one goal for Quacks is clearly to expose people to their narrative as much as their exposure to scientific consensus, regardless of the supporting evidence for either. Doing so creates an environment of false balance whereby opposing positions are perceived as being similarly supported by evidence, and the topic is then regarded as “up for debate”. We have seen this play out in nutrition with the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity. Despite being falsified countless times, the sheer number of Quacks that continue to perpetuate this narrative and cling on to the possibility that it “still might be true” means that it’s perceived as a topic of debate when it isn’t. A false balance in exposure manufactures scientific controversy and promotes public uncertainty where little truly exists. This strategy is used by Nutrition Quacks all the time: identify a potential scientific disagreement (even if the weight of evidence points incontrovertibly in one direction), create opposing sides of the debate, and then spam social media with a false narrative while telling themselves that no publicity is bad publicity.

If you want the most obvious example of this in the nutrition field, look no further than James DiNicolantonio’s Twitter feed. He tweets multiple times per day, usually with catchy titles like “7 GUT DESTROYERS”, while never posting anything with any substance or scientific validity. It’s pure attention-seeking that has enabled him to grow a large audience.

So my pointer is rather simple here: be extra cautious of people that post excessively on social media as if they’re really trying hard to convince you of something. Social media spammers are not necessarily Quacks, and I’m not saying that you must block them from your feed to reduce exposure—some people are just overly enthusiastic—but I would take what they’re saying with a healthy dose of scepticism. Further, I’d recommend finding people that post information with a purpose and when they have actually found something that is interesting and worth sharing—not to fill timeline gaps, not for personal gain, not to perpetuate misinformation, but to actually contribute meaningfully to the field.

5. An Absent or Inconsistent Epistemic Standard

The fifth pointer is that when an “expert” does appear to be evaluating or making claims based on scientific evidence, try to assess trends in how they reach their conclusions. You will find that actual experts have some type of logical consistency to justify the positions they do and do not hold.

Let’s take a hypothetical: if I say that I require well-conducted and well-adjusted prospective studies before inferring causality for a diet-disease relationship, then you’ll know I’m talking out of line if I start making causal claims based on an in vitro or rodent study from 1985; or, if I reject a causal relationship despite heaps of evidence that meets my pre-defined epistemic standard. So not only does this ‘standard’ help me to keep my personal feelings as separate as possible from the scientific method, but it also gives me a responsibility to think critically, knowing that everyone that follows my work is aware of how I reach conclusions. In this way, I’m forced to abide by the scientific method. So, if a nutrition “expert” that you follow clearly does not form their conclusions based on a pre-defined epistemic standard, then I’d question whether that person should be taken seriously. In these cases, knowingly or not, these individuals are likely using an evidential approach based on pre-defined beliefs rather than pre-defined standards for assessing data—this will only move us, as learners, away from the approximate truth. It’s the epitome of anti-science. Unfortunately it’s this exact belief-based reasoning (otherwise called ideology) that resonates throughout the nutrition field; it’s far too common for those mass distributing nutrition information to have no standard for evidence and no pre-defined system by which their positions can be questioned. When Quacks are called out for obvious inconsistencies in their judgement, they will simply move their evidential goalpost and hope onlookers don’t realise.

Not only do Quacks fall guilty of epistemic consistency, though, but they almost always try to flip the evidence hierarchy on its head, justified by some kind of educational enlightenment that scientists are wrong and research is highly flawed. This means that instead of basing opinions on well-conducted and robust interventional and non-interventional research (or meta-analyses of such), Quacks argue that mechanistic evidence is equally valid. I suggest that if you even get the subtlest of hints of this when an “expert” is trying to defend their claims, abandon ship immediately. The fact is that biological mechanisms, usually extracted from animal research, fail to extrapolate to human outcomes (according to expectations) the vast majority of the time. Even for medical drugs that tend to have a much stronger and direct biological target of action compared to nutrients, only a minuscule percentage of drugs that pass Phase 1 testing (for safety and proof of mechanism in humans) end up being approved by the Food and Drug Administration; most drugs either do not meet the required standards of efficacy or safety in later phases of testing. For this reason, thinking that a different reality exists for mechanisms of action in nutrition is utter nonsense and a sign of delusion. Even when a nutrition-related mechanism of action is “proven” to exist, if higher-level research examining human outcomes consistently contradicts the mechanism, then we must accept that the mechanism does not interact with the outcome in the way we imagined. Indisputable mechanisms do not necessarily translate into indisputable outcomes based on expectation.

The only reason why Quacks are blinded by mechanisms is that it allows them to justify almost any nonsensical position they please, albeit while violating Occam’s razor which states that “the simplest explanation that requires the least assumptions and leaps of faith should always be the starting point when formulating a position.” Quacks think detailed chats about biochemistry makes them sound authoritative and like they have a clue when they do not. So if an “expert” does not clearly emphasise the need to focus on higher levels of evidence, then know that their biochemistry talk is probably an indicator of epistemic delusion. Like it or not, nutritional knowledge isn’t driven by uncovering the actions of each nutrient on each regulatory protein; nutritional knowledge is driven by well-conducted interventional and non-interventional research assessing human outcomes. Quacks need to be informed they cannot rely on leaps of faith to speculate a grand idea of nutrition based on a mechanism(s) of action, while rejecting stronger positions based on more robust research with far fewer assumptions. They also need to be reminded that when faced with a rejoinder or contradiction to their position, they cannot simply add more assumptions and logical leaps to make it fit.

6. Cherry-Picking

The sixth and final pointer to spot a Quack is that when they decide to indulge in the scientific literature, they either misrepresent the study in question or the totality of the evidence base. We call this “cherry-picking” the evidence: the selective use of evidence to ignore details that contradict or undermine a faulty position purposely. This involves a selective fixation on data that chimes with ones position, while ignoring the totality of (stronger) evidence. It’s similar to the previous point about not applying a fair epistemic standard; however, cherry-picking pertains more to a failure in understanding study methodology, statistical analysis, and how to converge different sources of evidence.

Quacks essentially see what they want to see because of overwhelming bias rather than incontrovertible evidence. As one clear example, I’d recommend reading my article on dietary fibre and constipation as a rebuttal to misinformation spread by Dr Paul Mason. For years Paul made extraordinarily daft claims that “dietary fibre causes constipation” based on an in vitro and pilot study, while ignoring a myriad of well-controlled interventional studies that refuted his argument. He cherry-picked a minutia of the evidence base he could represent as “supportive evidence”. And this wasn’t a one off; Paul does the same thing to argue why polyunsaturated fats are more harmful than saturated fat by focusing on two studies that appear to support his claim (The Sydney Diet Heart Study and The Minnesota Coronary Experiment), while refusing to comment on a much larger pool of more robust evidence that clearly disagrees with his position. Both of these examples are clear cases of overgeneralising lacklustre evidence while sweeping inconvenient truths under the rug.

The only problem with this particular Quack ‘spotting method’ is that it requires one to have a fundamental knowledge of how to interpret research and the existing body of literature, which is admittedly a big ask for most people. Let’s face it, most people don’t even know that all forms of evidence and experiments are not created equal, let alone begin to interpret them with all their nuances. But this shouldn’t negate the importance of identifying a cherry-picker. Even the most basic data put forth by Quacks is often presented devoid of context and doesn’t require too much finesse or questioning to uncover. Simple data often shadows multiple layers of complexity and uncertainty. So just be aware that some Quacks have nailed this skill—presenting data in the most persuasive way rather than the most representative—and enjoy asking more questions.

Final Thoughts

I hope this article has provided you with a fresh perspective on nutrition misinformation, or maybe just confirmed what you already knew. For me, it was a necessary piece to write. Nutrition misinformation appears to be spreading rapidly with no reliable way for a reader to decipher fact from fiction. I could continue my rant forever here but I’ve said enough—I will save further thoughts on ‘what to do’ to prevent nutrition misinformation for another article. For now, as will I, please continue to reflect on your thoughts, know that spreading misinformation has real-world consequences, and keep trying to identify and promote trustworthy sources of information.

If you have enjoyed this article and want to support the website, please consider donating to the website, joining our Patreon, and signing up to our email list below. Any contributions are highly appreciated. Thank you.