Chronic constipation is a gastrointestinal disorder characterised by hard stools, infrequent bowel movements, abdominal cramping, bloating, excessive straining, and the sensation of incomplete defecation. Some people might perceive constipation as an embarrassing condition to suffer from but it’s more common than expected. The estimated prevalence of constipation in American adults, for example, is 20%. Suffer no more, though, as a wide range of effective treatments are available. Most people will find benefit to small lifestyle changes as first-line treatments (increasing dietary fibre and fluid) while clinical options are available if all else fails, such as laxatives and colon surgery. That’s the briefest of summaries anyway.

In recent years, however, a medical doctor named Paul Mason has posted a series of articles and videos trying to debunk dietary fibre as a nutrient that helps to prevent and treat constipation. In fact, Paul has gone as far as to make extraordinary claims that dietary fibre is actually the cause of constipation and exacerbates symptoms in those who are already suffering. Sounds controversial? Indeed. Given the inherent nature of the internet, though, these claims have been popularised and are now viewed as a topic of scientific debate. I’ve gone as far to see Facebook groups with thousands of members who genuinely now believe that dietary fibre is a nutrient to be avoided at all costs for digestive health. Of course, too, knowing that dietary fibre is a component of edible plants while being largely absent from animal foods, such an argument is subsequently being used to promote widespread consumption of an animal-dominated diet.

In this article, I will dissect Paul’s quotes and scientific references to clarify why he’s not only portraying a narrative that is demonstrably false, but is also presenting an argument that misrepresents the basics of constipation pathophysiology. As a side note, given that Dr Paul Mason is continually building a following of health enthusiasts–so they claim–I would also like this article to offer an insightful look at the (lack of) critical analysis skills that Paul uses to formulate his arguments. Paul is becoming a popular figure in the low-carbohydrate space but I believe he holds many controversial and dangerous opinions that unjustly oppose scientific consensus.

Paul’s few lines of argumentation on this topic will be covered independently:

- “Dietary fibre does not moisten the stool”.

- “Dietary fibre causes constipation”

- “There are no studies showing that increasing dietary fibre improves constipation and its related symptoms”

“Dietary Fibre Does Not Moisten the Stool”

In case you’re unaware, the primary mechanism by which dietary fibre prevents and treats constipation is by increasing the water content of the stool. This leads to easier flow through the gastrointestinal tract and excretion from the sphincter. It also takes only a relatively small change in the water content of a stool to result in large changes to its consistency: liquid stool is ~90% water content; soft stool is ~77% water; formed stool is ~75% water, and hard stool is ≤72% water. This 18% difference in stool water content from liquid to hard stools makes all the difference; stool viscosity (a measure of resistance to flow) can actually increase up to 240% based on such changes in water. For this reason alone, although there are numerous reasons why constipation may often be unrelated to diet and stool consistency, constipation can be a result of hard stools that are, by nature, more difficult to pass through bodily systems. In turn, dietary guidelines and national health organisations recommend an increase in dietary fibre as one means to prevent and treat constipation.

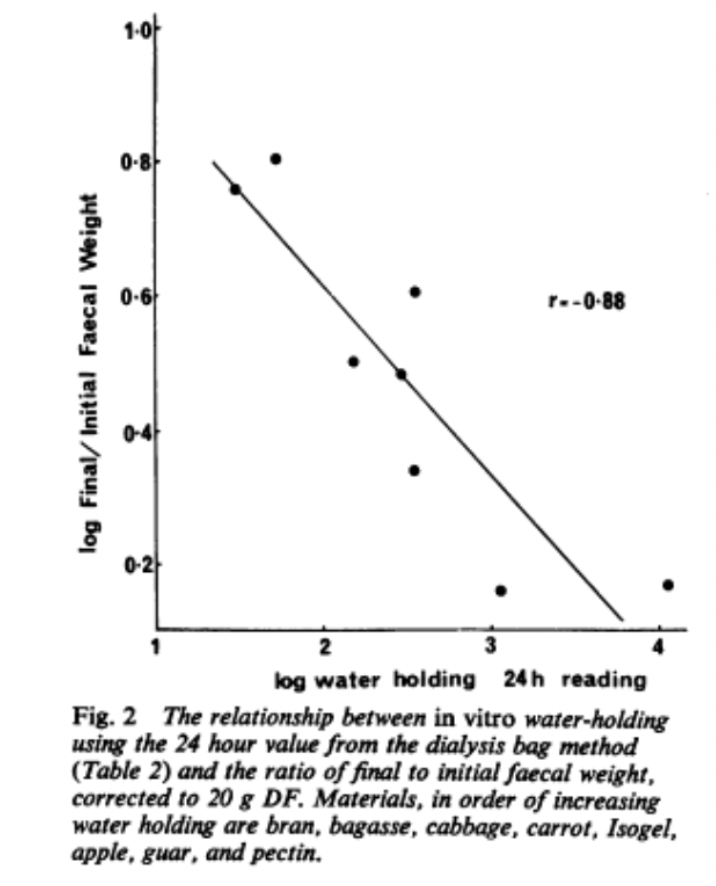

Paul, however, argues that fibre’s influence on increasing stool water content is wrong. It’s not a claim that’s grounded in science, he says. But why? What evidence does he have to oppose scientific consensus? Well, throughout all of the times I’ve heard Paul speak on this topic, I’ve only ever seen use one reference to support his claims, alongside generally arguing for lack of data in support of fibres’ moistening effect. The reference that I’m referring to comes at minute 6:00 of Paul’s talk at a low-carb conference, for example, when he states that “people will also say well [fibre] moistens the stool, except it doesn’t. It’s been long known and well understood that stool moisture does not vary regardless of how much fibre or how much water you consume. Fibre does not moisten the stool“. Now, at least with one reference to support such a strong statement, you would expect it to be some sort of meta-analysis, systematic review, or perhaps even a robust prospective trial. But no. The apparently long-known and well-understood evidence that fibre does not moisten the stool turns out to be a 1979 in vitro experiment on the water-holding capacity of dietary fibre and its relationship to faecal bulking in man.

What the study tested was a new method of measuring water uptake by 17 different types of dietary fibre, known as the dialysis sack method. This method requires ~50mg of each fibre to be placed into a small sack of dialysis tubing, before then being added to a test solution that mimicks the composition of the human terminal ileum and right colon. In this particular study, the bags were weighed to assess for a fibre’s water uptake at 24, 48, and 72 hours (the weight of water held per gram of dry material). Once the data were obtained, the fibres’ water holding capacity was contrasted with the results of controlled human experiments analysing faecal bulking in response to various dietary fibres. And based on this comparison, there was a surprising inverse relationship found between the water-holding capacity of dietary fibre in vitro and concomitant effects on faecal bulking in human trials. Cool.

So is this study all that Dr Paul Mason hypes it up to be? Well, clearly not. As always, we must consider the assumptions of this particular study and how it fits in with the wider body of literature, to help contextualise the findings. For example, one study assumption is that gut composition and dynamics are well-replicated in vitro using, well, a gut-mimicking and non-dynamic bag. That’s hard to believe. Another assumption is that the water-holding capacity of just 50 mg of fibre within the bag can be reliably scaled up to the ~20 grams of fibre used in the comparative human experimental studies. That’s also hard to believe.

So is this study all that Dr Paul Mason hypes it up to be? Well, clearly not. As always, we must consider the assumptions of this particular study and how it fits in with the wider body of literature, to help contextualise the findings. For example, one study assumption is that gut composition and dynamics are well-replicated in vitro using, well, a gut-mimicking and non-dynamic bag. That’s hard to believe. Another assumption is that the water-holding capacity of just 50 mg of fibre within the bag can be reliably scaled up to the ~20 grams of fibre used in the comparative human experimental studies. That’s also hard to believe.

Also, even if we want to take a leap of faith and accept these assumptions, we still don’t end up with Pauls conclusion that this study proves dietary fibre doesn’t moisten stools. A more appropriate takeaway would be that the water-holding capacity of the various fibres analysed, by this particular in vitro dialysis method, do not appear to translate to the respective fibre’s capacity to bulk faeces in actual human experiments. Many of the fibres do clearly hold enormous amounts of water—which was actually the reason only 50mg was used as some bags were otherwise perforated—they just didn’t translate across to human data as expected. That’s fine, and an interesting finding, actually.

But the problem with Paul’s take here is that science ultimately progresses and, since this study was conducted in 1979, we now have a more extensive understanding of dietary fibre that Paul fails to represent in his communications. Probably the most critical point is that the intrinsic water-holding capacity of dietary fibre is only half the reason why fibre increases the water content of stools. In addition to this mechanism, dietary fibre can also stimulate the gut mucosa and enable water and mucous to be secreted into the intestinal lumen. As such, it is not only the intrinsic water-holding capacity of dietary fibre that can increase stool water content, but also the mechanical nature of fibre throughout the gastrointestinal tract.

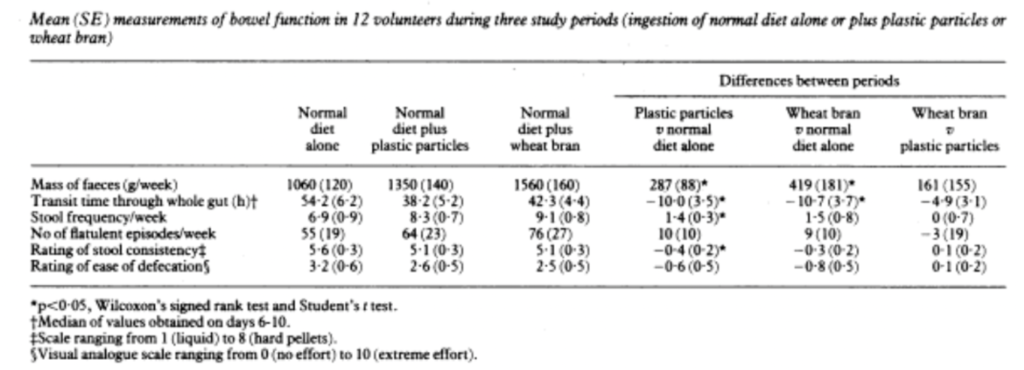

This secondary mechanism was strangely discerned by experiments using plastic particles cut to match the size and shape of certain dietary fibres. For example, the first experiment of this kind was by Tomlin and Read in 1988 by way of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) with a crossover design. The study had healthy participants consume their normal diet, and then with the addition of either plastic particles or wheat bran that had been matched to provide the same amount of residue to the caecum. And by assessing stool photographs, the consistency of the stools was significantly softer—indicative of increased water content—after the consumption of plastic particles or wheat bran, with no significant differences between the two interventions. Regardless of the intervention, there was notable stool softening, reduced gut transit times, and even an improved ease of defecation.

Yes, that is me quite literally saying that consuming inert particles of a certain size and shape can help you to defecate, as strange and illogical as that might sound. The reality is that being able to easily excrete stools is not all about stool bulk, but also about how easy it is for that stool to be passed through the gut and rectum. The plastic particles were able to have essentially the same laxative effect as the wheat bran fibre for this reason, with replication studies by Lewis and Heaton in 1997 and 1999. The authors of these studies concluded with the statement that “Overall, the present data support the concept of roughage, i.e, that a laxative effect can result from solid particles in the intestine if they are of appropriate morphology”.

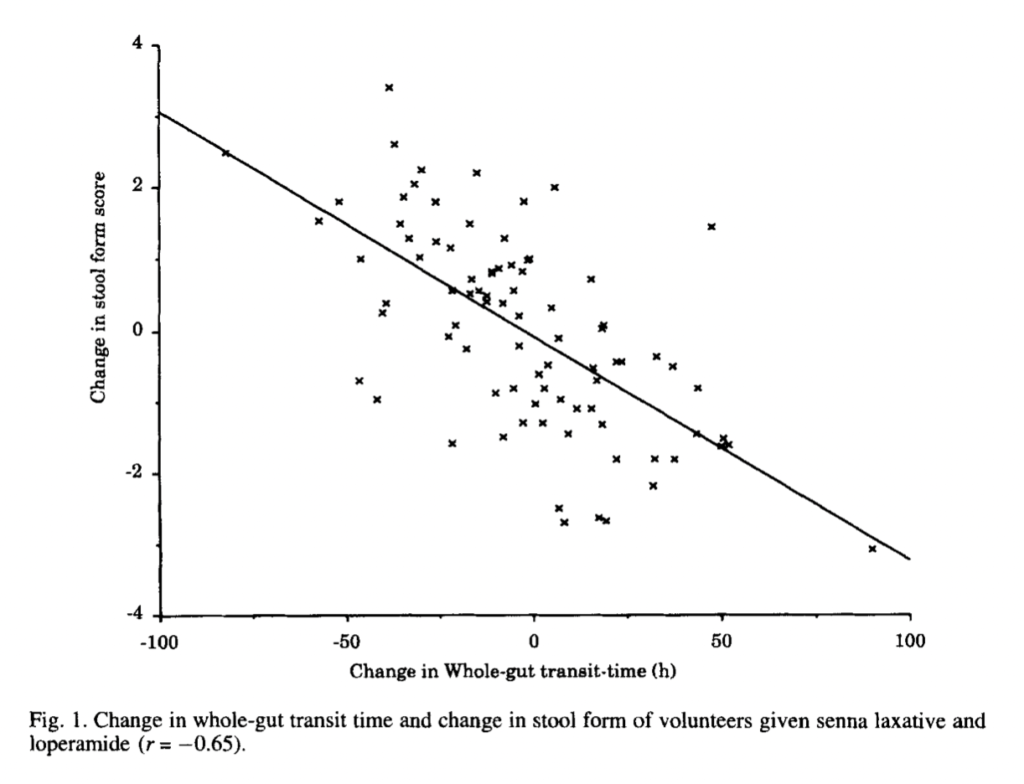

There might also be a third reason why dietary fibre stimulates water and mucous secretion into the intestine, which is that it can reduce gut transit times. Using validated wireless motility capsules (VCMC), we know that by adding ~10 grams of fibre to a low-fibre diet (15 grams) in healthy individuals reduces whole-gut transit time by 8.9 hours and colonic transit time by 10.8 hours. Now how this relates to stool water content can be argued, but it’s thought that the less time it takes for a stool to pass through the colon, the less water is absorbed by the colon and the more water remains present to form part of the stool. RCTs from Lewis and Heaton have helped to show that changes in stool form correlate with changes in transit times when analysing stool form changes in response to medical laxatives and bulking agents.

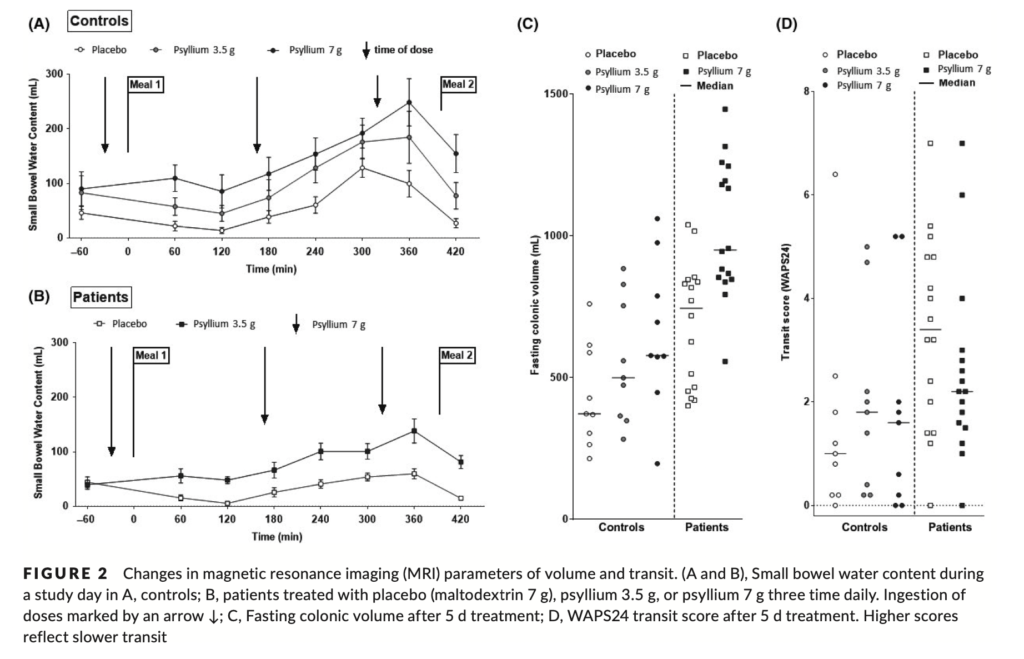

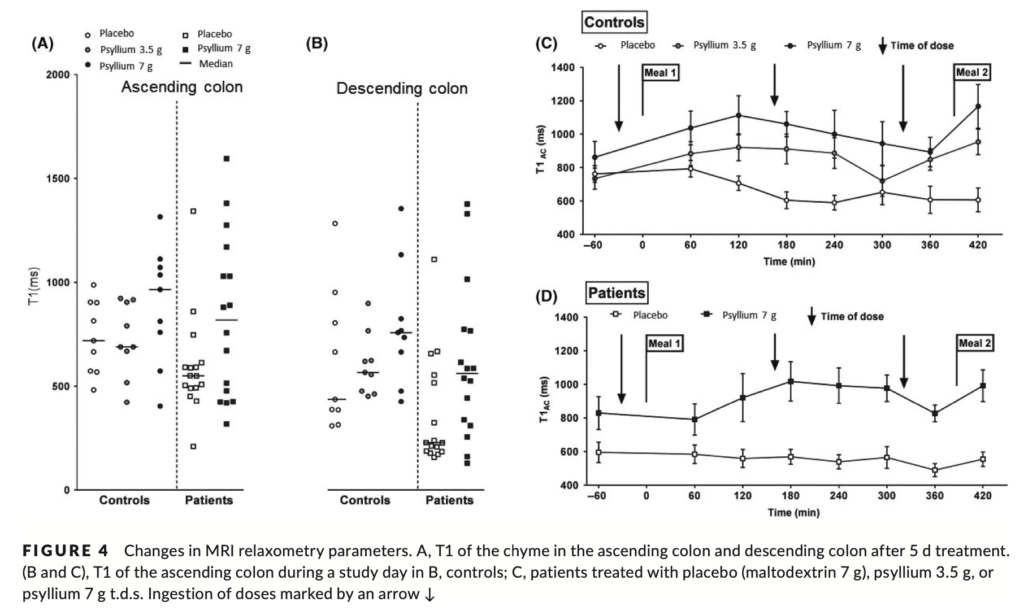

Perhaps stronger evidence comes from a recent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) experiment by Major et al. This study looked at psyllium fibre supplementation and subsequent effects on the small bowel and ascending colon water content, colonic volume, transit time, and colonic chyme. Two placebo-controlled crossover studies were actually conducted in the overarching experiment: one recruited adults without GI disorders (controls) and another using a similar methodology but with chronic constipation patients. Both studies used either placebo or psyllium fibre (3.5 grams or 7 grams) for 6 days, followed by a one-week washout. On day 6, patients were subject to multiple MRI scans after the ingestion of transit markers, while regularly consuming fibre or placebo alongside morning and afternoon meals. MRI scans were taken at hourly intervals for 7 hours to be precise. The results were novel and groundbreaking. Therapeutic doses of dietary fibre three times daily with food led to significantly increased postprandial small bowel water content in participants with and without constipation, and the effect was sustained for the full 7 hours measured. In those without constipation, the water content of small bowel water content was increased even while fasting. This led the study researchers to suggest that fibre appeared to trap water in the small bowel by increasing viscosity throughout the gastrointestinal tract, thereby impairing convection and reducing water access to the intestinal mucosa where absorption otherwise takes place.

As this study also used faecal samples to measure stool water content at enrolment and after the final MRI scan of each treatment period, the researchers also found that stool water content was significantly higher than baseline after fibre supplementation in both constipated and non-constipated patients. The effect seemed to be stronger in the constipated patients with harder stools at baseline (absolute change in stool water content from fibre supplementation was 6.2% in constipated patients, on average).

Overall, the ability of dietary fibre to increase stool water content is not restricted to the water-holding capacity of the dietary fibre itself. Dietary fibre can increase water content through various mechanisms, including stimulating the gut mucosa, reducing gut transit time, and trapping water in the small bowel via increased luminal viscosity. Paul’s narrative that fibre cannot increase stool water content and only bulks out the dry mass of faeces to make excretion harder is wrong. The evidence presented here clearly contradicts his statement that “adding fibre to bulk out the faeces makes no more sense than adding cars to clear a traffic jam. Just really illogical”.

A Note on Dietary Fibre Type

Before we continue onto Paul’s next claim, I want to clarify that just because there is clear evidence that dietary fibres can increase stool water content, this doesn’t mean that all fibres will necessarily do so. The reason why is that, analogous to other nutrients such as dietary fat and carbohydrate, dietary fibre is not a single entity: fibre is a class of compounds with very different physicochemical characteristics. Surprisingly, in all of Paul’s discussions about dietary fibre, I’m actually yet to hear him distinguish between different types of dietary fibre, instead opting to generalise the entire category as useless and contraindicated for human health. However, a fair assessment of the nutrient would appreciate that variations in dietary fibre structure result in distinct levels of viscosity and fermentability, which ultimately influence each fibres function within the gastrointestinal tract.

We can separate dietary fibres into ‘soluble’ (high affinity to water) and ‘insoluble’ (remain as discrete particles), and also ‘fermentable’ (digested by gut bacteria) and ‘nonfermentable’ (pass freely throughout the gastrointestinal tract). Not all of these characteristics are beneficial for increasing stool water content and aiding excretion. For example, fermentable fibres don’t hold the same potential benefit for preventing and treating constipation because, once fermented, the fibre is no longer intact and thus lacks the properties required to improve stool form. This explains why readily fermentable fibres have shown in systematic reviews of well-controlled RCTs to almost always (14 of 15 studies included) have no significant effect on stool output or stool water content, and have little to no laxative effect. This doesn’t mean nonfermentable fibres are “bad” for constipation as Paul likes to suggest; rather, fermentable fibres aren’t the type to focus on if increasing stool water content and normalising stool form is a concern. In fact, these differences are one of the primary reasons why there exists such conflicting data in the dietary fibre literature. Meta-analyses of dietary fibre often have high heterogeneity for this reason, pooling a lot of studies using different types of fibre into the same analysis. This point was discussed in a recent narrative review of dietary fibre meta-analyses with the author stating that “large heterogeneity exists in the fibre literature as a result of the different physicochemical properties of the various fibers, different fiber dosages and treatment durations, and differing participant characteristics”. So, even though Paul and I can agree that there are certainly some single dietary fibre types that don’t appear to benefit stool form or constipation, this observation should not be generalised to the entire dietary fibre category. If certain fibre types are of benefit and others not, then we can still conclude that some fibres help to prevent and treat constipation.

“Dietary Fibre Causes Constipation”

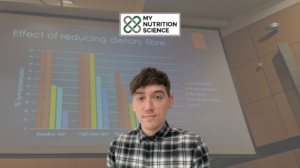

With all the above said, we must now turn our heads to the second reference that Paul likes to throw about in support of the idea that dietary fibre causes constipation. The paper in question here is a preliminary study by Sun-ho et al. looking at the effects of dietary fibre on the symptoms of constipation in a small group of individuals with idiopathic constipation. Paul has made a couple of bold claims based on this study alone, including the claim that “increased levels of fibre intakes are associated with significant disturbances of gout function, you get constipation, you get bloating, people generally don’t feel very well”… “[this study], to date, is the only experimental design that has ever looked at changing the amount of fibre in the diet on symptoms of constipation”. We will come to the latter claim shortly but first, let’s address whether this study supports the claim that increasing fibre causes constipation.

In short, the study had a group of doctors instruct their idiopathic constipation patients, all of which had a high dietary fibre intake at baseline, to “completely stop” dietary fibre intake for 2 weeks. After 2 weeks, the patients were then asked to continue with as much fibre in their diet as they were comfortable with. Patients were followed up at 1 month and 6 month intervals, at which point patients were categorised into either ‘no fibre’, ‘reduced fibre’ or ‘high fibre’ groups. The results of the study were that, at 6 months, 41 patients continued on a no fibre diet, 16 were on a reduced fibre diet, and the remaining 6 patients continued on a high fibre diet. Further, the patients who remained in the no dietary fibre group at 6 months all reported complete resolution of constipation and its related symptoms, whereas those in the reduced and high fibre groups continued to have symptoms.

Paul uses this study to perpetuate the narrative that, in contrast to scientific consensus, fibre only increases the dry mass of stool and therefore makes faecal excretion harder. This narrative is interestingly pushed aswell by one of the study authors—who I contacted via email—who also took the position that dietary fibre just adds unnecessary stool volume. “Less fibre, less stool. Less stool, easier evacuation”, he said. However, let’s address a couple of critical points.

The first is to accept there were some pretty major flaws to the study design here. Importantly, the no dietary fibre intervention was not strictly true. Participants were instructed to reduce their consumption of some high-fibre foods (wholegrains, vegetables, and fruits) for 2 weeks, but never to eliminate fibre. The intervention would have been more appropriately labelled as a reduced dietary fibre intervention for this reason–I presume participants still consumed some amount of fibre. Additionally, although this seems rather bizarre, there were literally no measurements for dietary fibre intake throughout the entire trial, meaning that baseline and post-intervention dietary fibre intakes were not objectively measured. This raises a red flag given the patients were grouped into levels of dietary fibre intake. I assume the doctors just grouped patients based on their perceived fibre intake during clinical discussions, but this opens itself up for a boat load of subjectivity between doctors’ perceptions and patients’ self-reporting. Big problem.

But for the sake of argument let’s move past these faults and accept that lowering dietary fibre intake did actually improve constipation and its related symptoms here. Does this mean that we can claim that dietary fibre causes constipation? Well, when this is the only evidence to support that claim, absolutely not.

We should accept that the aetiology of preventing complex conditions is extremely different from improving symptoms when the condition is already present. This is important because the underpinning causes of constipation are extraordinarily vast and often have little to no relation to dietary fibre intake or nutrition at all for that matter: causes may be primary (related to intrinsic gastrointestinal structure and function) or secondary (related to systemic disease or medication). The latest overview of human defecation physiology–that sounds weird–explains that factors leading to constipation involve one or a combination of abnormalities in colonic motor activity, the central nervous system, the rectoanal pressure gradient, anal dilation, stool form, and even obstruction. Consequently, symptom improvements from dietary changes will often relate only to (transient) symptom management as opposed to treatment of the underlying pathology. In turn, the reduction in patient’s symptoms shouldn’t be used to support the position that “fibre causes constipation”. Instead, the results can support that when there are unknown issues with defecation that are unlikely to be resolved by increasing dietary fibre intake, effectively reducing gut residue and stool bulk can help to improve symptoms. This is not exactly new information either: the guidance for many gastrointestinal disorders already states that dietary fibre intake should only increase after the highly symptomatic episodes are resolved or the chronic disease is managed.

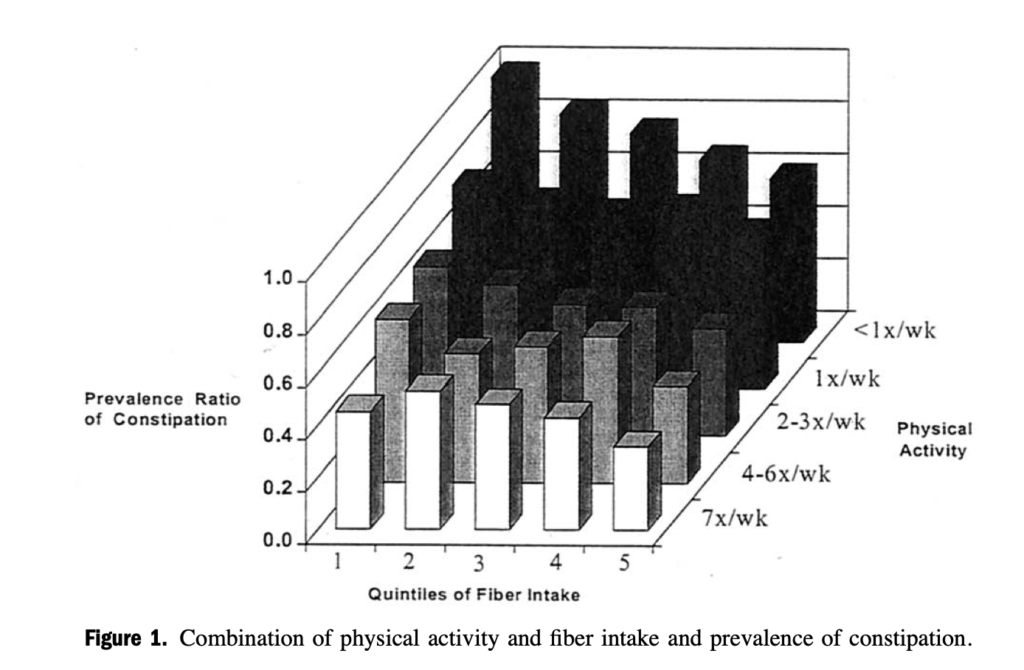

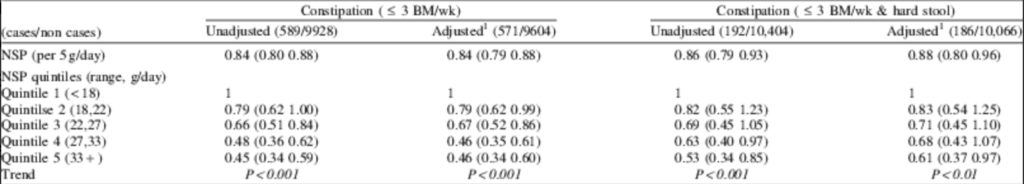

Paul will probably argue all night about the distinction between symptom management and causality here. The unfortunate reality for him, though, is that we have a great number of RCTs showing that constipation symptoms can be improved by correcting a fibre deficiency (discussed in the next section). We also know that at a population level, low fibre intakes are a risk factor for constipation. For example, large-scale evidence from cross-sectional and prospective cohort studies, such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2010, the Nurses Health Study, and the UK Women’s Cohort, all report that increased fibre intakes are associated with a reduced risk of developing constipation.

The Nurses Health Study

The UK Women’s Cohort

“There are no studies showing that increasing dietary fibre improves constipation and its related symptoms”

This flows into the next section here pretty well, given if it were true that dietary fibre was “the cause” of constipation, we probably wouldn’t ever expect to see improvements in constipation and its related symptoms from an increase in dietary fibre intake, right? Paul has previously stated that “to date, [the Sun-ho et al. study is] the only experimental design that has ever looked at changing the amount of fibre in the diet on symptoms of constipation”. This is not true. Here are just some studies to prove that Paul’s statement is demonstrably false:

- Two high-quality RCTs found that dietary fibre in the form of hydrolysed guar gum or a fibre mixture achieved comparable results in the treatment of childhood constipation when compared to the lactulose laxative. This included an improvement in stool consistency, the relievement of stool withholding, and a reduction in abdominal pain.

- An RCT comparing mixed fibre and psyllium in patients with chronic constipation found that both were equally efficacious in improving constipation and quality of life. Mean complete spontaneous bowel movements per week significantly increased from baseline with both fibre interventions, with a 75% positive response rate from patients. Significant improvements were found in stool consistency, straining, and bloating.

- In an RCT trial at a medical centre, when compared to baseline, 3-4 weeks of increasing either kiwifruit, prune, or psyllium intake significantly improved weekly bowel movement rate and straining in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation. Patients randomised to the kiwifruit group also reported significant improvements in bloating.

- In an RCT on the effects of ‘vege-powder’ (consisting of chicory, broccoli and whole grains) in constipated adults versus a control group, those who received vege-powder had significant improvements in symptoms of constipation (including stool hardness, defecation frequency and straining to defecate) at 2 and 4 weeks.

- In another RCT of chronic constipation patients, when compared to semi-skimmed milk, fibre-enriched milk product significantly lowered the proportion of patients with straining during defecation, the sensation of incomplete evacuation, the sensation of obstruction, and the days between bowel movements.

- A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of fibre in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation found that not only is fibre effective in treating chronic constipation in adults, but that high dose fibre supplementation (>15 g) was the most effective, with a number needed to treat of only 2.

All of these studies are more rigorous and tightly controlled than the single human intervention presented by Paul, and they clearly refute his claim that there’s no evidence showing that increasing dietary fibre improves the symptoms of constipation. Paul should stop making this claim. Taking into account the evidence presented above, and also the interventional study put forth by Paul, I think it’s fair to conclude that both increasing and decreasing dietary fibre intake can improve the symptoms in patients with constipation. The right approach should be judged on a case-by-case basis with the help of a health professional. I will say, though, that it appears only the correction a fibre deficiency may prevent the onset of constipation and relate to the condition causally. This conclusion aligns better with what we currently know of constipation pathophysiology, the observational literature, and also the totality of relevant RCTs.

Final Thoughts

There is clear evidence that dietary fibre can increase the water content of stool and improve stool form. Observational evidence suggests that a low fibre intake is a risk factor for developing constipation, and there are numerous tightly controlled studies showing that an increase in dietary fibre intake can improve the symptoms of constipation in those suffering from the condition. In cases where the causes of constipation are likely unrelated to diet, a temporary low-residue diet including a lower intake of fibre may help to improve the symptoms of constipation until the root cause(s) is identified and treated.

To date, Paul Mason has misrepresented the literature on the pathophysiology of constipation and its relevance to dietary fibre intake. He relies on poor interpretations of scarce in vitro data and a poorly controlled human intervention while ignoring the majority of the literature of more rigorous RCTs. He also ignores reviews contextualising dietary fibre results with stratification by dietary fibre type (fermentable vs nonfermentable).

If you have enjoyed this article, please consider supporting the site by donating here and subscribing to our email list below (we don’t spam!).