Extended Summary

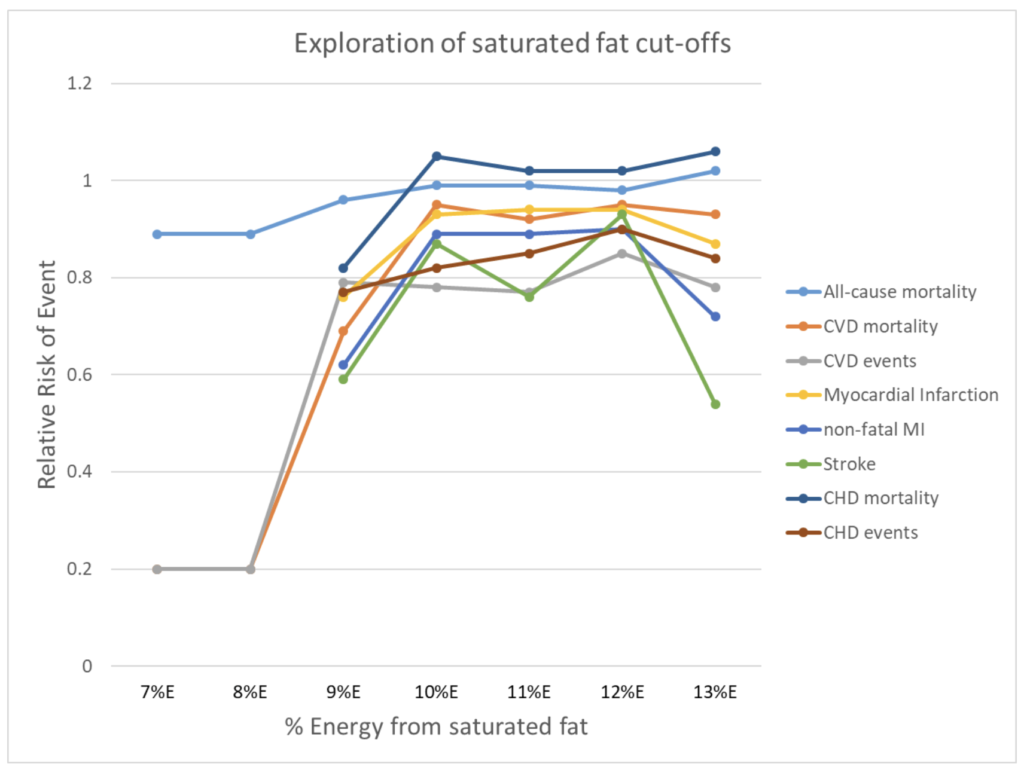

Most of the research portrayed as ‘disproving’ the link between saturated fat and cardiovascular disease are studies without an intervention, such as prospective cohort studies. Non-interventional studies are not intrinsically problematic when reviewing the claim; however, an arising issue is that most studied populations (in the United States, Europe, Canada, and Australia) consume a diet with a moderate to high amount of saturated fat (>10% of total calorie intake). As a result, it’s notoriously difficult to assess the potential benefits or harms of a low saturated fat intake without a dietary intervention. This methodological issue alone has led to confusion about the relationship between saturated fat and cardiovascular disease, since a lot of popular studies report a neutral effect without actually testing the efficacy of a low saturated fat intake.

But when analysing randomised trials that achieve a low intake of saturated fat via intervention, the reduction in cardiovascular disease risk becomes clear. Numerous meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials, including dose-response analyses of saturated fat intake, conclude that reducing saturated fat to below 10 % of total calories lowers the risk of cardiovascular events. Said differently, achieving a low saturated intake is required to maximally reduce cardiovascular disease risk. Failure to achieve this level of intake will either increase someone’s risk of cardiovascular disease or, if they already consume a high amount of saturated fat, keeps them at a relatively higher risk of the disease. Unfortunately, capturing this change in risk is only possible when researchers acknowledge the importance of testing a wide contrast of saturated fat intakes, which most do not.

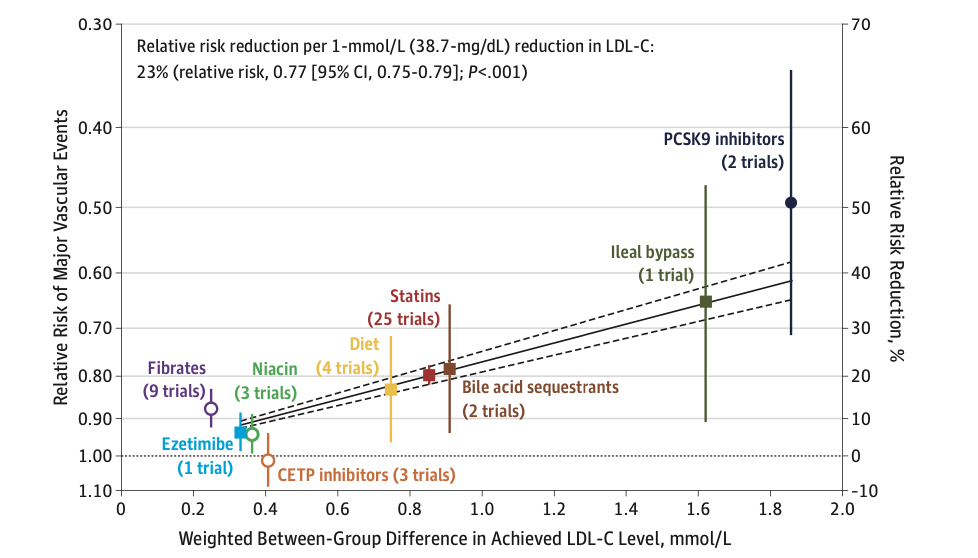

The amount that cardiovascular disease risk changes depends on the extent to which changing saturated fat intake influences circulating levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C; a fundamental cause of cardiovascular disease). Interestingly, meta-regression analyses show that, for any given change in LDL-C, the substitution of dietary fats offers as much benefit to reducing cardiovascular deaths as medical and surgical interventions. How much saturated fat influences LDL-C, though, depends on what nutrient it’s replacing in the diet, or what it’s being replaced with; a review of clinical studies clearly establishes that LDL-C increases when saturated fat replaces carbohydrates in the diet, and LDL-C decreases when saturated fat is replaced by unsaturated fats. What is now known as the Keys equation can predict, with good precision, the effect of saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids in the diet on serum cholesterol levels (a proxy for LDL-C).

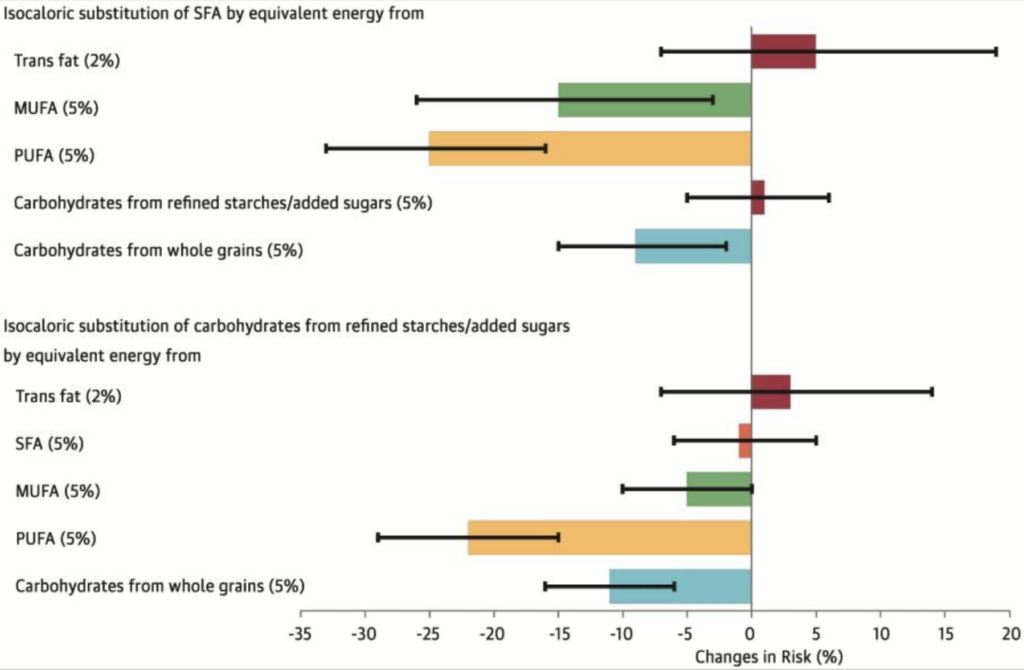

Similarly, when discussing the risk of saturated fat on cardiovascular disease, a pivotal and often overlooked question is ‘compared to what?’. Given other nutrients have their own relationship with the risk of cardiovascular disease, replacing saturated fat with different nutrients can lead to either a net benefit, harm, or indifference. For example, a few prospective cohort studies, in addition to another meta-analysis of randomised trials, show that substituting 5% of calories from saturated fat with either polyunsaturated fat, monounsaturated fat, or complex carbohydrate associates with a 9 – 25% reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease. However, replacing saturated fat with refined carbohydrates or trans fats confers no benefit and may even increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. The distinct effects between replacement nutrients, then, is a critical consideration for the reviewed claim. Studies that fail to measure the impact of different replacement nutrients are not pinpointing where a potential benefit or risk lies, and these studies miss the diametrically opposed effects of different replacement nutrients. Unfortunately, this methodological limitation pertains to a large pool of relevant literature and is another reason why conclusions about ‘no risk’ or ‘no effect’ are misleading and dangerous.

To add more nuance, we note that some foods with a high saturated fat content, such as eggs, chocolate, and certain types of dairy (yoghurt and milk), are not linked with the same increase in cardiovascular disease risk as the general category of ‘saturated fat’. The reasons for these differences are still under investigation but likely stem from the fact that we consume foods, not isolated nutrients. It’s plausible that some foods have sufficient protective properties (such as the presence of other nutrients, or the food matrix in which saturated fat is metabolised, etc.) that outweigh the potential harms of saturated fat. For example, a complex food matrix in some forms of dairy fat seems to reduce dietary fat absorption and cause relatively less changes to LDL-C compared to other foods high in saturated fat. It’s also plausible that some foods which mostly contain a type of saturated fat known as stearic acid, such as chocolate, will not increase the risk of cardiovascular disease compared to other types of saturated fats. Similarly to the food matrix of dairy, comprehensive reviews of dietary fats and lipoproteins observe that stearic acid (an 18-carbon saturated fatty acid) does not increase LDL-C to the same extent as other types of saturated fats, if at all.

Additive to the prior point, we also note two errors in reasoning as to why the lesser harm of certain foods high in saturated food shouldn’t be used to disregard the effect of saturated fat on cardiovascular disease risk. First is that we shouldn’t conflate the effects of individual foods with a diet that is high in saturated fat. Even when there is a high dietary intake of foods like dairy, for example, a high saturated fat intake is still associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease; there is currently a lack of evidence that suggests we can bypass the risk of a high saturated fat diet by focusing on select food sources. Second, the differences in risk between high saturated fat foods is largely irrelevant to the risk differences between all foods—the wider substitution effect of replacing saturated fat with foods high in unsaturated fats still applies. The benefit of dairy fat, for example, is most evident when replacing another saturated fat source such as meat. But current evidence, specifically from multiple dose-response analyses of prospective cohort trials, and analysis of high-dairy consuming populations such as Finland, still supports the established hierarchy of benefit of replacing saturated fat, even from dairy fat, with polyunsaturated fat—it’s just a lesser benefit compared to the replacement of other saturated fat foods. So while we emphasise that dietary sources of saturated fat are preferably sourced from eggs, chocolate, and certain types of dairy (yoghurt and milk), the associations between these foods and cardiovascular disease should not grant claims about saturated fat not increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease in certain doses.