The dietary guidelines are a set of recommendations to help the average person remain healthy. They were introduced in 1980 and get updated every 5 years by 20-ish scientific experts, including a mix of practitioners, epidemiologists, scientists, and clinical trialists. To save you reading them for context, as they span a meaty 164 pages, I’ll loosely summarise them here: eat your fruits and vegetables, and reduce your intake of sugar, saturated fat and sodium. Basically what your Mum told you.

Recently, however, the guidelines have been attacked. To a new breed of nutrition enthusiasts, the dietary guidelines are terrible, the root cause of health problems in the modern world, and pending trial for all their harms. Now of course this is nonsense, but I’m bored on this dreary Monday evening, so let’s address it.

Newsflash, People Don’t Like to Eat Salad

The most hilarious thing about this attack on the dietary guidelines is assuming the average person actually eats this way. Like, I’m not sure what friends these people have, but mine aren’t fighting about who’s bringing salad to the party. To state the obvious, most people like eating pizza, fried chicken and donuts, a lot. I don’t think some quite appreciate how bad the average persons diet is.

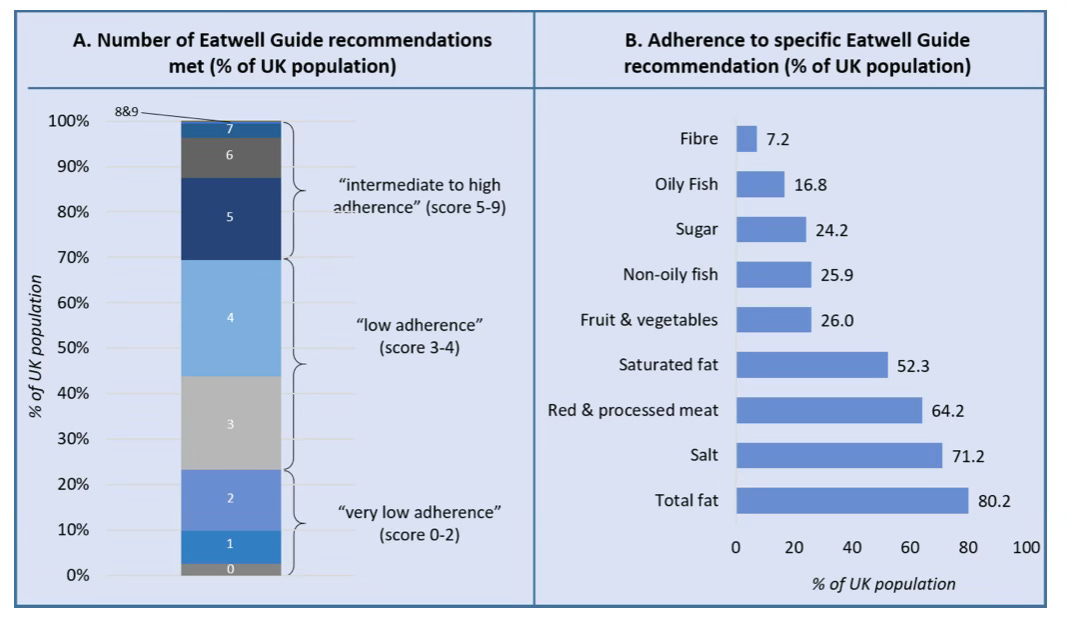

Of the four main guideline recommendations (≤10% saturated fats, ≤10% free sugars, ≥25 g/day fibre, ≥5 servings of fruits and vegetables per day), nearly a third (29.7%) of adults in the UK do not follow any of them, just over a third (38.5%) follow one of them, about 1 in 5 (22.3%) follow two, and about 1 in 10 (9.5%) follow three or four. Or if we were to use the famous ‘Eatwell plate’ as a guide, which is split into 9 common dietary recommendations, less than 0.1% of people follow all of them. So basically, if we take “following the guidelines” as people who literally check of all the boxes, then unfortunately that leaves basically nobody (not even me). A rather brutal review of dietary guideline adherence in the United States revealed the same trend… "nearly the entire U.S. population consumes a diet that is not on par with recommendations" said the researchers.

So What Happened in 1980?

When it boils down to it, the only real “argument” that people have against the dietary guidelines is that around the time they were introduced, population health got progressively worse. But the lack of adherence to the dietary guidelines is enough to know this observation is almost definitely a coincidence. Although timeline comparisons are very popular on social media – “since event Y followed event X, event Y must have been caused by event X” – this type of analysis is extremely susceptible to post-hoc fallacy. By scientific standards, these sweeping observations are literally among the weakest forms of “evidence” that one can muster up from the dustbin. So much changed socioeconomically in the 70s and 80s that to pluck some eating guidelines out the bag of possible causes of chronic illness is, well, laughable.

In my opinion, the most plausible explanation for progressive health issues since the 1970s-ish, especially the rise in bodyweight, is the rapid change in the food supply that occurred around this time period. Consumers started to have increased buying power alongside a reduced cost of food, all while the food industry was increasing the accessibility of more energy-dense and hyperpalatable foods (yes, this basically means tasty foods).

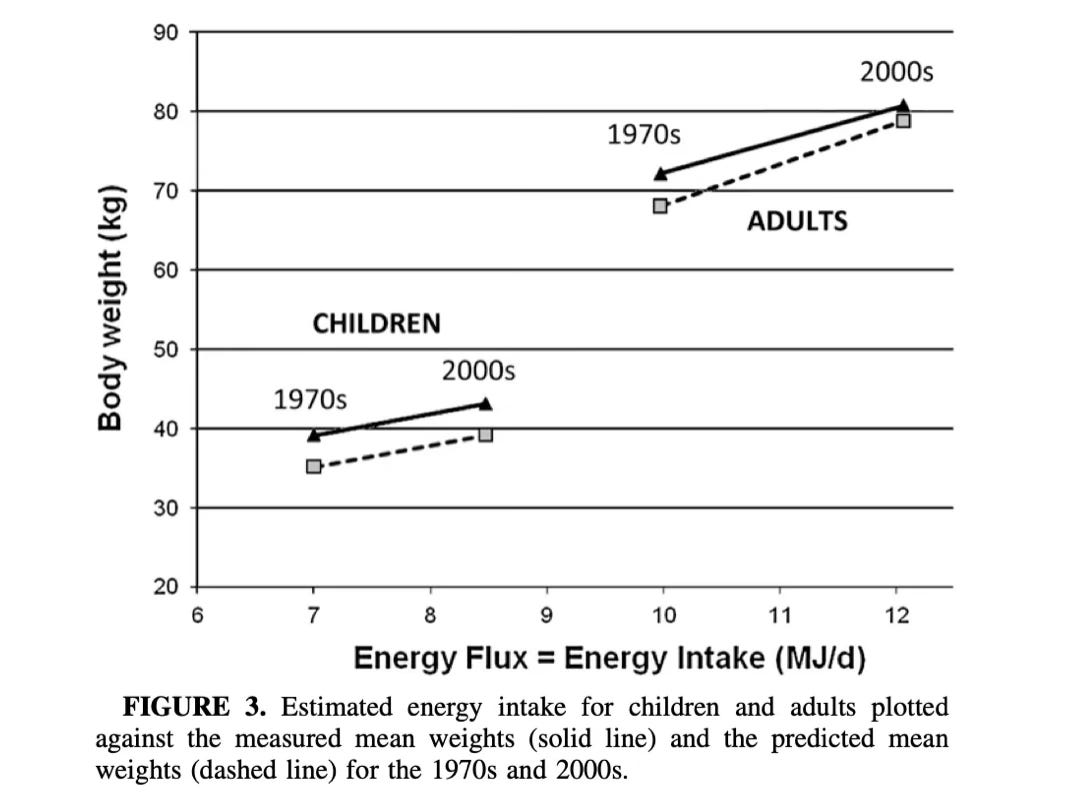

One particularly interesting analysis by Swinburn et al. found the increased food energy supply since the 1970s was enough to explain the obesity epidemic in the United States. The researchers correlated changes in food energy availability per capita (as a proxy for changes in energy intake; and after consideration for food waste) against changes in bodyweight, from the 1970s (1971–1976) to the early 2000s (1999–2002).1 On average, food energy availability per capita increased by 500–700 kcal per day, which predicted a substantial upward shift in bodyweight – more than was actually observed in reality. That’s about two donuts.

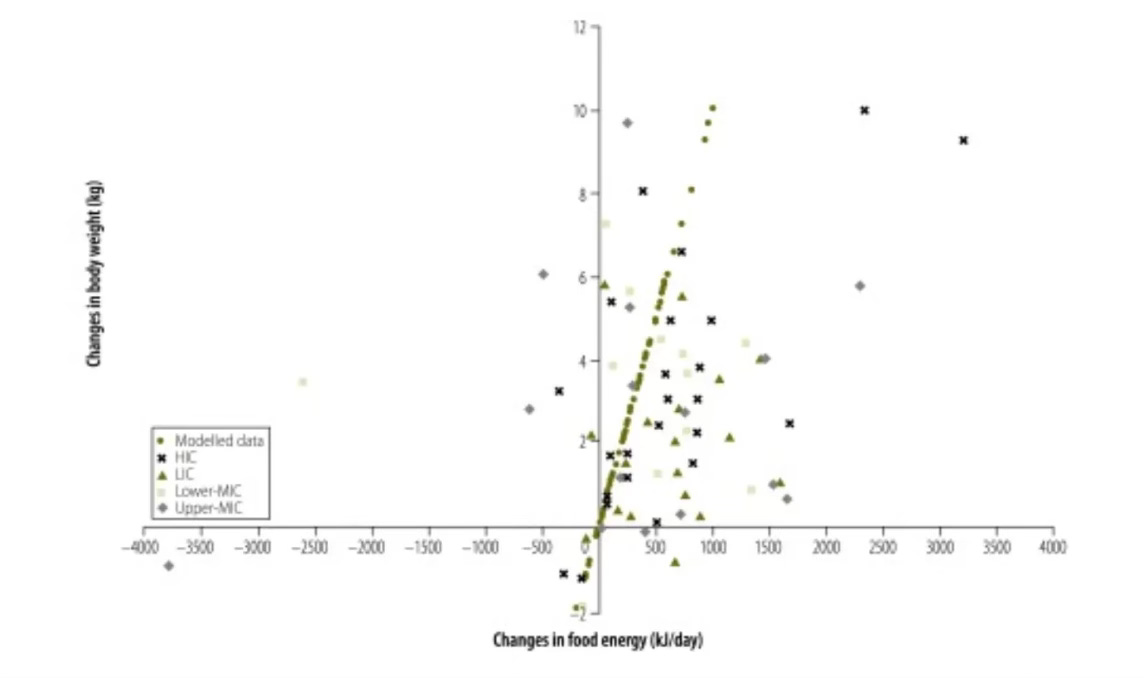

Since this study, Vandevijvere et al. published a more global analysis that tested for the same effect across countries. The researchers collected data from global databases, national health surveys and peer-reviewed studies to assess bodyweight changes in 69 countries from 1971-2010, only using data derived from study pairs at least four years apart. What they found was that for 56 (81%) of the countries, both food energy supply and bodyweight increased in tandem. Plus, for 45 of the countries (65%), the increase in food energy supply was more than sufficient to explain the increase in average body weight.

But Let’s Stick to More Robust Data, Shall We…

While we can spend a lifetime hypothesising about why things happened in the past, it’s better to focus on what our reality is now. For example, we can look at studies that check if people following the dietary guidelines more closely tend to be healthier. And guess what, they do.

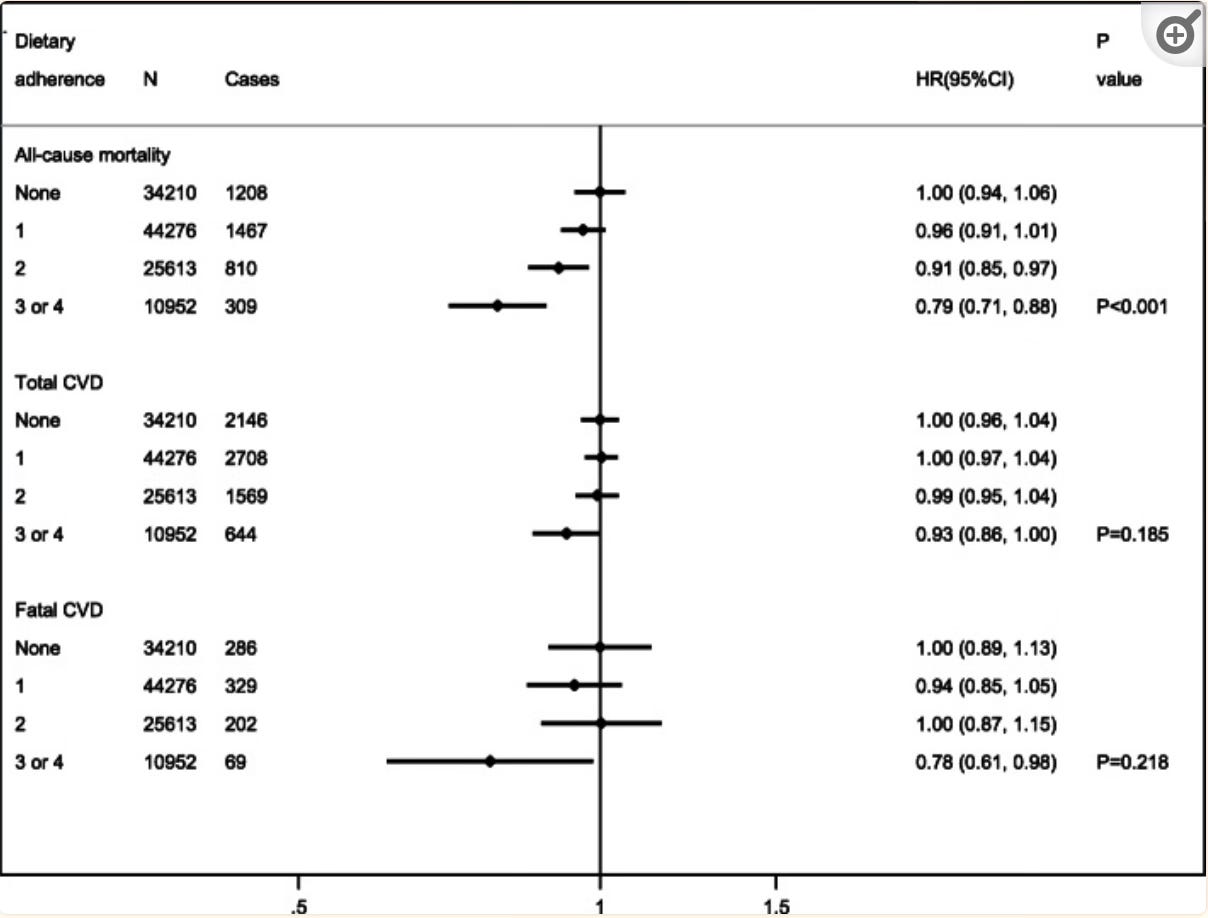

In one study, researchers analysed 115,051 participants with data on dietary intake, cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality across an average of 10 years. They looked at the strict achievement of the four dietary goals (that I mentioned at the beginning of this article) and the number of these dietary recommendations that people met (1 through 4, using 0 as the reference category). The statistical analysis was then stratified by sex and adjusted for a range of factors including total daily energy intakes, smoking status, alcohol consumption and physical activity. Based on this, the researchers reported that people meeting 3–4 guidelines had a 21% reduction in all-cause mortality versus people meeting 0, with a significant trend across the stepwise increases in adherence. Adherence to 3–4 guidelines was also associated with a 7–22% reduced incidence of total and fatal cardiovascular disease compared with 0.

Another couple of large studies agree with these results, that being The Copenhagen General Population (CGP) Study and The Shanghai Men's and Women's Health (SMWH) Study. Both of these studies also analysed over 100,000 adults and had 10–15 years of follow-up analysis. All participants’ diets were assessed at baseline, after which participants were grouped into 4 (SMWH) or 5 (CGP) adherence categories ranging from very low to very high. The results were that all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality were 13–43% and 12–46% lower, respectively, in individuals with very high versus very low adherence to dietary guidelines.

Very similar benefits have been found in smaller cohort studies (ranging from 1,000 to 10,000 individuals) in Australia, Finland, Italy, and the Netherlands. This is a pretty consistent observation. Therefore, the overall evidence base strongly suggests that greater adherence to the dietary guidelines reduces the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular-specific mortalities. Make sure you tell that to the next person shouting about how the dietary guidelines were made to kill us.

A Little Bit of Clarity

Beyond this evidence, I want to finish on a more general point that often goes amiss. That is, much of the criticism for dietary guidelines is simply due to misunderstanding what the intentions of the guideline's intentions are, and how they should be implemented in public health policy. People assume the dietary guidelines are trying to position themselves as the holy grail of dietary advice and suitable for everyone, when in fact that is not, and has never been the case.

What is actually stated in the latest version of the US dietary guidelines is that the dietary guidelines are “not intended to contain clinical guidelines for treating chronic diseases” and that “a healthy dietary pattern is not a rigid prescription. Rather, the Guidelines are a customizable framework of core elements within which individuals make tailored and affordable choices that meet their personal, cultural, and traditional preferences". Also, the dietary guidelines state they have been "developed and written for a professional audience” and “it is essential that health professionals adapt the Dietary Guidelines to meet the specific needs of their patients as part of an individual, multifaceted treatment plan for the specific chronic disease.”

The above quotes from the dietary guidelines speak volumes to those criticising them for supposedly promoting hard and out rules to the public. Just the word guideline should be a clear giveaway to their intended purpose - they are a guide, not a rule. Yes, many of the guidelines recommendations have nuances and details not discussed in the document itself, but that is why they target a professional audience with the knowledge to interpret and adjust the information to their target audience. So, if you’re not one of those professionals, how about, for once in your life, you just shut up. (Just kidding, I know most of you mean well and are pretty knowledgable!).

Speak soon!

The validity of this type of analysis was confirmed by the USDA, who stated that food supply data provides a useful indicator of trends in consumption because most errors in the data are likely to be systematic, i.e. it's the contrast in energy availability changes over time that matters rather than accurate measures of absolute values.

I've always found the food supply/energy availability data to be more compelling and circumnavigates some of the issues in relating estimated energy intakes to population-wide weight trajectories. Great article mate.